Metra has a board meeting coming up next Wednesday, which means @OnTheMetra will update their Twitter profile with Metra’s updated on-time performance figure, with a healthy dose of snark. (You’ll be able to livestream the board meeting here.) Metra’s on-time performance remains something of an inside joke among regular Metra commuters, since it’s always significantly higher than it feels. February’s on-time performance (OTP) was officially 92.3%, which sounds high but officially is one of Metra’s lowest OTP in quite awhile. (Metra had a streak of more than two years with OTP above 95%.) As far as peer agencies go, Metra’s OTP is actually pretty impressive: the Boston T’s commuter rail OTP is usually in the low-90s; likewise with CalTrain in the San Francisco Bay area; the Long Island Rail Road in New York City trends in the mid-80s; and Philly’s SEPTA muddles in the low-80s. So we should count our blessings that suburban Chicago has one of the best performing commuter rail systems in the country, right?

Kinda. (I mean, of course I’m grateful for Metra — believe it or not, Diverging Approach and Star:Line aren’t solely intended to crap on Metra all the time. Relative to other commuter railroads, Metra isn’t terrible. But it could be so much better and so much more user-friendly, which is where we come in.)

Let’s back up and go over how commuter rail agencies determine on-time performance. A train is considered “on-time” if it arrives at its last station within 5:59 (5 minutes, 59 seconds) of its scheduled arrival time. So for instance, BNSF Saturday train #1312 is scheduled to arrive at Chicago Union Station at 12:47pm. If that train arrives at Union Station at 12:52:59pm, that train still arrived “on time”. In the grand scheme of things, six minutes isn’t the end of the world, so on its surface it’s a decent metric for an agency that runs rail lines that can be over sixty miles long.

But Metra — and, to be fair, most other commuter rail agencies — figured out they can game the system a bit. Going back to the common thread of “Metra moves trains, not people“, the last line of the Metra schedule gets a little fuzzy as far as what it’s meant to tell you. Since no one boards the train at the last station, there’s really no incentive for the time of arrival shown to have much bearing on reality other than maintaining a respectable on-time performance. Put another way, imagine doing online tracking of a package from UPS or FedEx. They might tell you that your package will be delivered “today before 7:00pm”. Your package could arrive at 2pm or 6:59pm, and in either case, they were right. Your package arrived on-time. Again, this doesn’t seem to be that big of a deal on the surface: if Metra gets me downtown earlier than they said they were going to, cool. More time downtown to do fun stuff.

And here’s the catch: with an on-time performance goal of 95%, all Metra has to do is to make sure that last time listed on the schedule for the train is within six minutes of actual arrival times for 95% of trips. If on-time performance starts to slip, just slide those arrival times back a few minutes until 95% of the trains are on-time again, even though the train is actually slowing down for whatever reason. And again, that’s fine… if you adjust the entire schedule. Metra doesn’t.

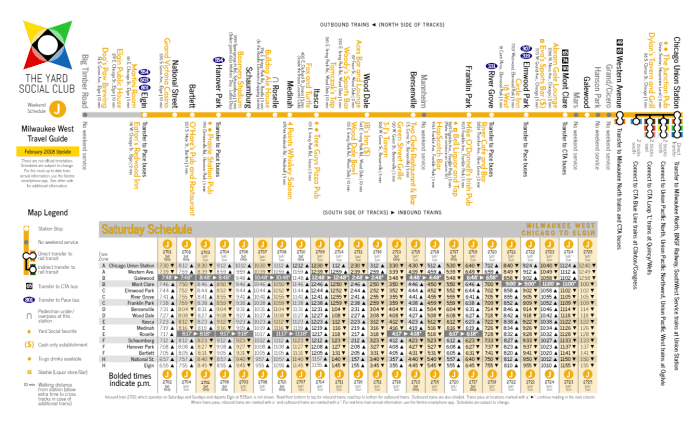

Here’s Metra’s inbound Saturday BNSF schedule from April 2007.

And here’s Metra’s current inbound Saturday BNSF schedule.

These are almost the exact same schedule. Same number of trains, same departure times leaving Aurora, same intermediate stop times. Trains 1300, 1302, 1304, 1322, and 1324 are literally the exact same.

But look at the rest of those trains and what time they arrive at Union Station. I mentioned train #1312 earlier (and you thought it was a random example!), which still leaves Western Avenue at 12:24pm but now takes an extra five minutes to travel the four miles into Union Station. Did something happen with the tracks between Western Avenue and Union Station that dramatically slowed down trains? According to the same current schedule, Western Avenue to Union Station can be made in 15 minutes or less (weekday train #1296). So why do those middle trains take longer to go from Western Avenue to Union Station?

Three words: heavy passenger loading.

Maybe Metra’s worst excuse for delayed trains (“we didn’t anticipate so many people wanting to ride the train!”), those trains tend to be the most delayed for a variety of reasons: could be track construction, could be freight train interference, could be signal issues, could be anything, but quite often it’s because so many people got on the train earlier on the line and the train needed extra time to board everyone. (You’d think that delays frequent enough to require schedule changes would trigger someone to think that maybe there’s enough ridership to support more than one train every two hours in the afternoon, but here we are.) But once again, Metra only needs to make sure that 95% of trains get downtown before the last time listed on the schedule, so they can keep sliding that last arrival time back further and further to maintain a favorable OTP. (Construction schedules are particularly egregious in this respect. Thirty-four minutes to go from Clybourn to Ogilvie!) And this happens throughout the system, not just on the BNSF. If the train was hauling a commodity, the schedule makes perfect sense: we’ll pick up three tons of corn at LaGrange at 12:03pm; have the shipment ready at that time and we’ll pick it up then or shortly thereafter, and we’ll get it downtown no later than 12:47pm. But once again, Metra is – or at least needs to start thinking of themselves as – a transit agency, and people are not bulk commodities to be shipped. The value of time for a suburban resident waiting on a train is significantly higher than a farmer’s yield, and as we’ve seen throughout the country, transit riders aren’t afraid to pay a premium for prompt rideshare service instead of waiting.

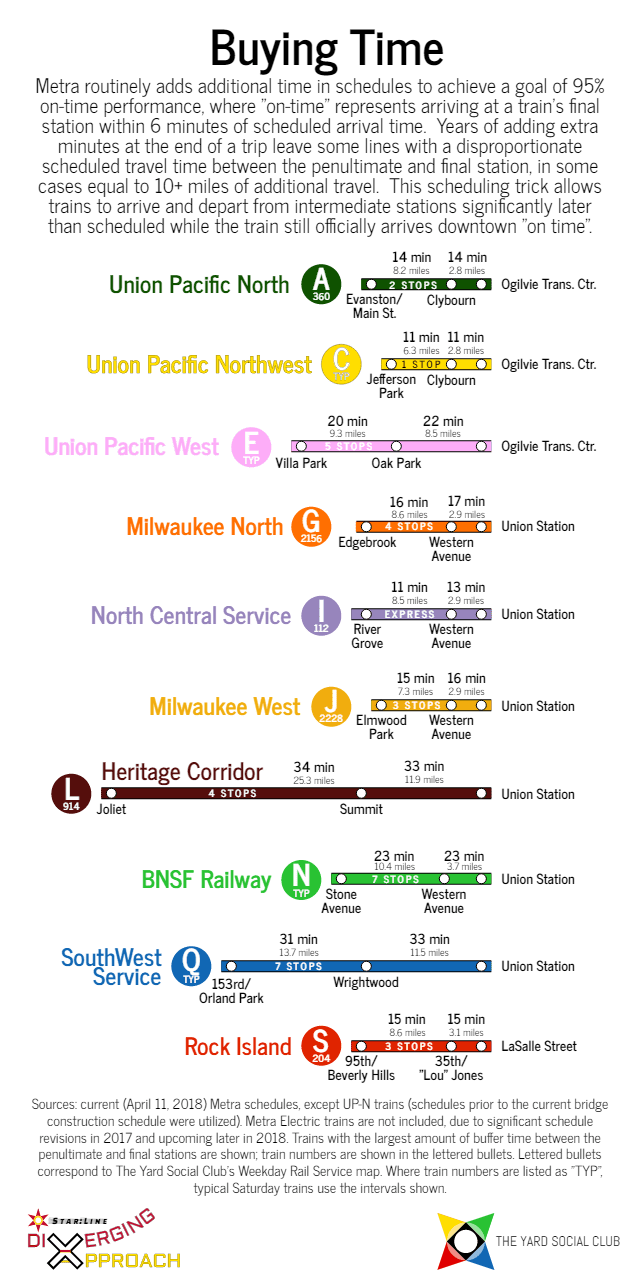

The following graphic shows the longest duration in the current schedule between the second-to-last station and the downtown terminal for each line, and the corresponding travel time approaching the second-to-last station, including additional stops the train makes. As you can see, in some cases the schedule shows the train taking as long to travel the final few miles as it does to travel halfway down the line and make other stops on the way in.

This leads to a situation I call a “Schrödinger’s Delay” that pisses off riders and ends up being a self-inflicted wound for Metra, since the train is simultaneously delayed and on-time. Let’s go back to BNSF Saturday train #1312, which I frequently use to head downtown on the weekend. That train is scheduled to pick me up at LaGrange Road at 12:03pm, and it’s usually late. As mentioned earlier, weekday train #1296 can run Western Avenue to Union Station in 15 minutes (and that likely includes some time padding as well), but the Saturday schedule gives train #1312 a gratuitous 23 minutes. So we know there’s already at least eight minutes of time padding in there. Throw in the 5:59 grace minutes, and a train can arrive at LaGrange Road as late as 12:16pm, make all the scheduled stops 13 minutes behind schedule, and arrive at Union Station officially “on time”.

From an optics perspective, waiting on the platform in the elements (outside a station that’s locked on weekends) for a train that picks you up 13 minutes late just to have Metra tell you, “no, that train was actually on time“, is probably not the best long-term strategy for Metra and won’t help to attract new riders or make the system any easier to use. Even worse, regular riders can get used to the delay and know to show up a few minutes late until eventually the train comes as scheduled, and then people complain about Metra being on time. (Side note: be nice to @Metra on social media. There is an actual person who reads all the tweets.)

I understand that this issue is not specific to Metra, but honestly I don’t think that matters. If you want to build your ridership and make the system more user-friendly, revise your schedules regularly to reflect actual operating conditions, don’t just keep throwing extra minutes at the end of the line. If Metra wants to keep touting their on-time performance with monthly press releases (that mysteriously stopped coming out once OTP slipped below 95% starting last December), fine, but at least maintain some internal metric regarding schedule adherence and try to create some accountability to have schedules that match what riders expect, especially when you’re only running one train every hour or two hours. We live in the age of Uber and Lyft, where I can randomly choose to summon a stranger on the internet to pick me up and they’ll tell me exactly where he is and how long he’ll take to come get me; it’s not to much to ask for that, if I’m going out of my way to get on a train that comes once every two hours, that train comes when you say it’s going to come… and if it’s late, admit it’s late, and put some effort into making sure it won’t be late again.

Reminder: Metra is still accepting comments on the proposed revisions to the BNSF weekday schedule. (No changes to the weekend schedule are proposed at this time, so everything above will likely continue to be true for awhile.) We have plenty of issues with the proposed schedule, and we’ve submitted our comments, but we encourage you to give your feedback to Metra as well. The comment period closes Sunday, April 15; send your comments to BNSFservice2018@metrarr.com.