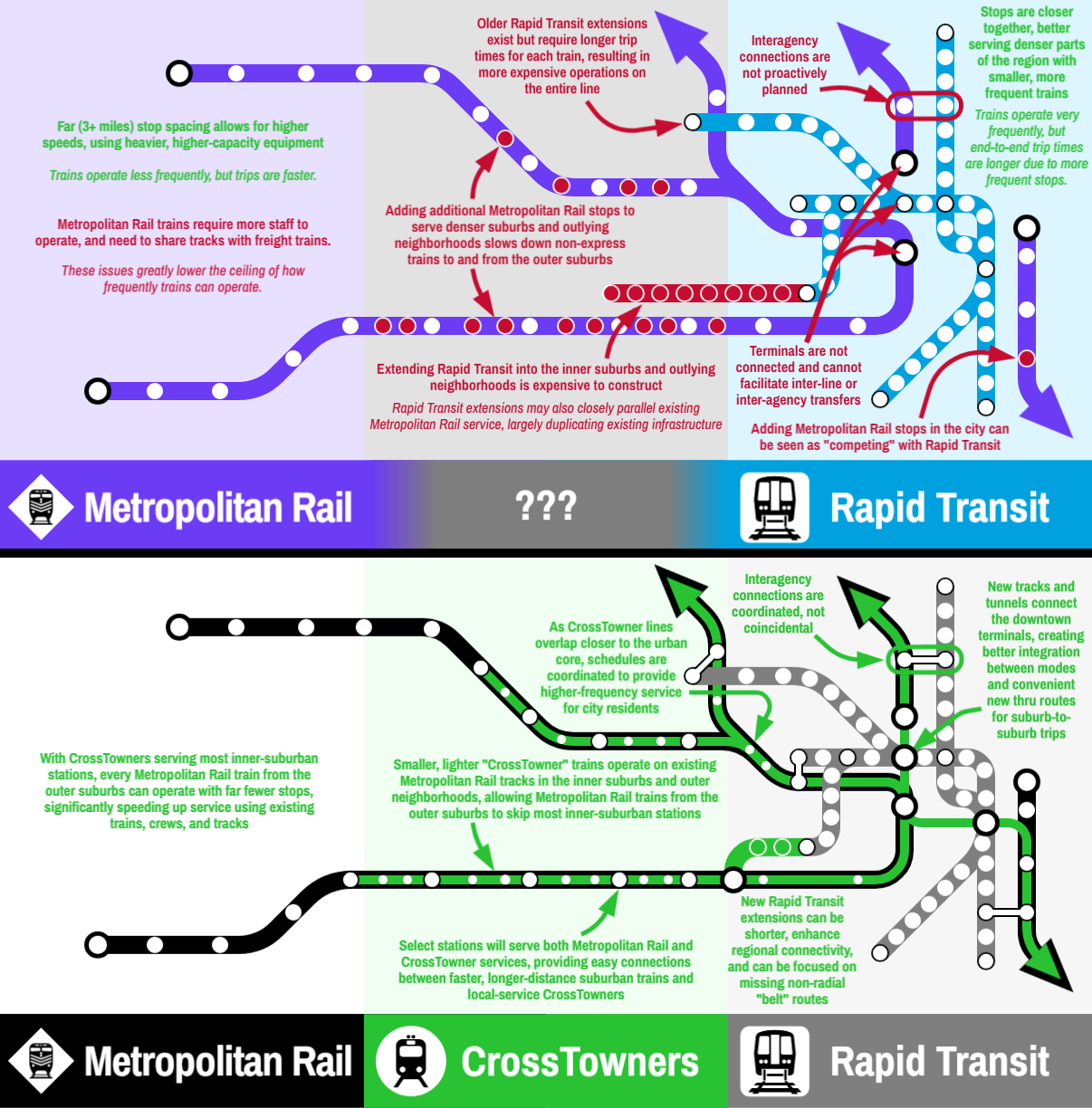

Regular readers of this blog are already familiar with the benefits of a thru-running regional rail network, and why specifically here in Chicagoland we need to #BuildTheTunnel.

It can be challenging, however, to envision how such a system could be crafted, developed, built, and operated; indeed, it is one of the most common questions we’ve received. There are multiple existing constraints that need to be identified and mitigated, and major capital projects that would need to be built. The Chicago Terminal, as railroaders generally refer to the Chicagoland rail network, is an incredibly complex place to operate trains.

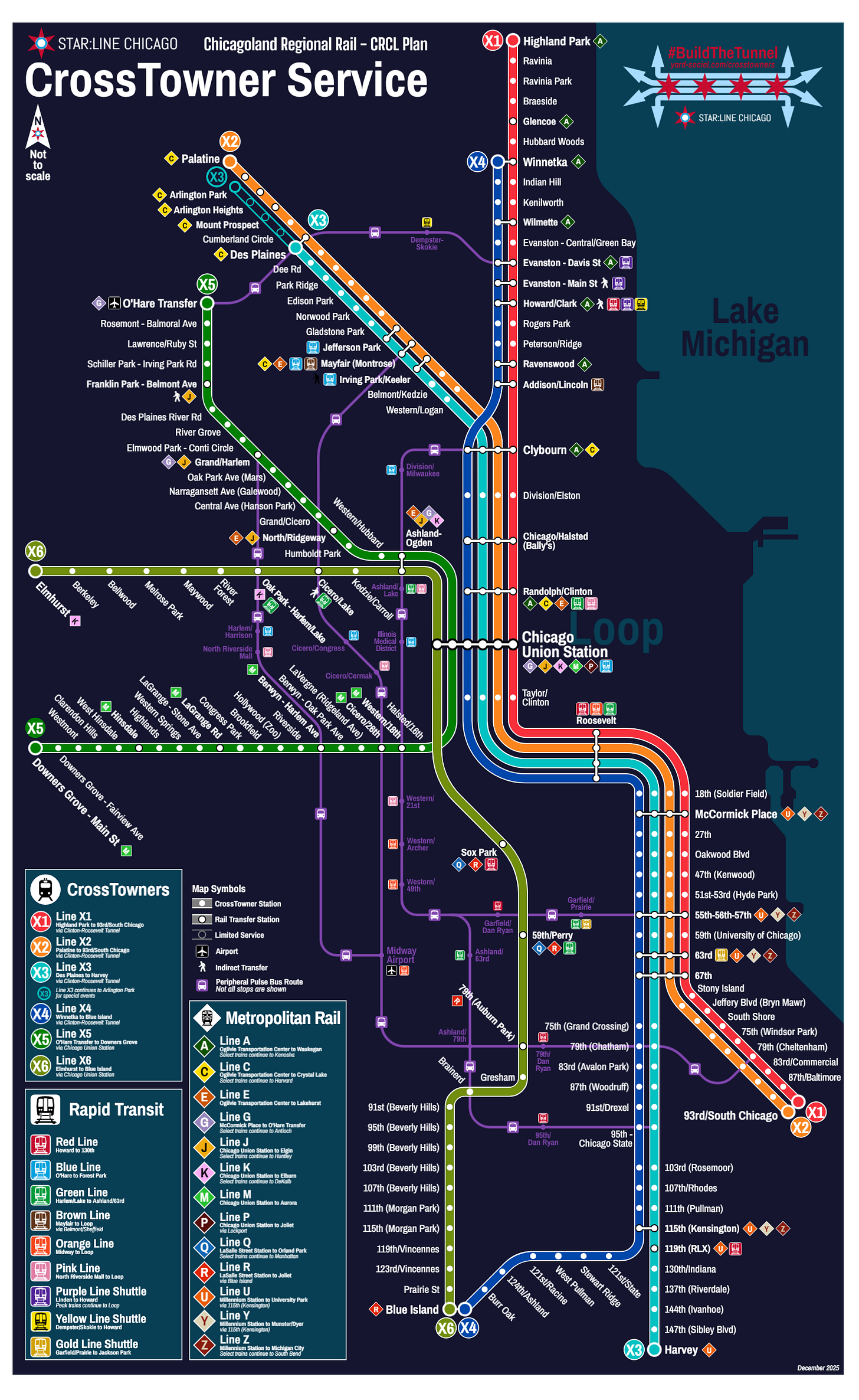

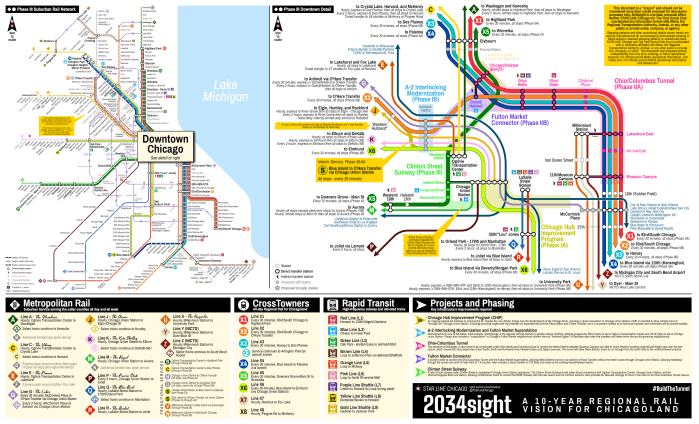

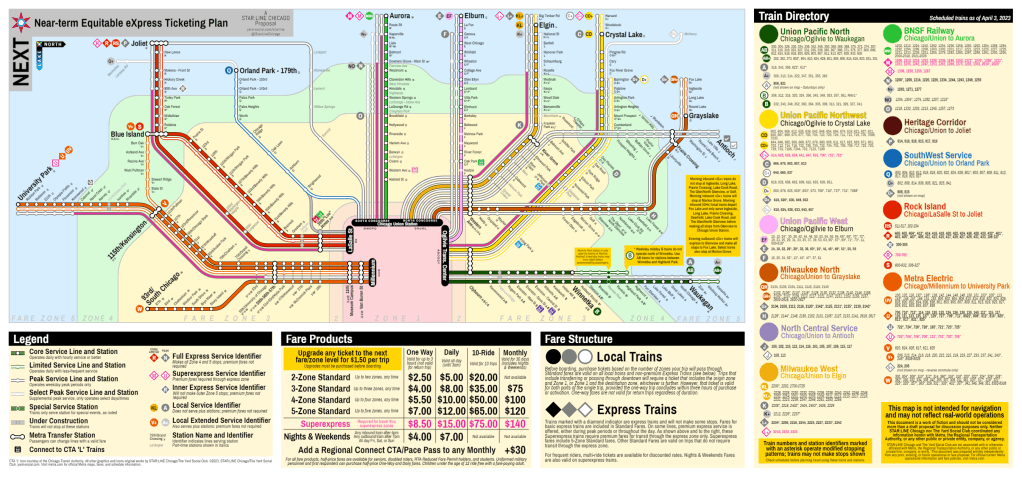

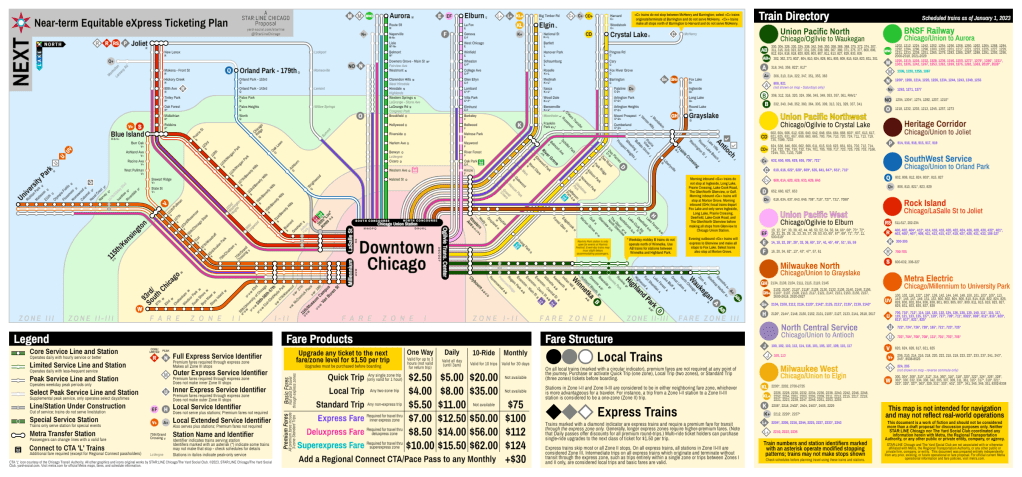

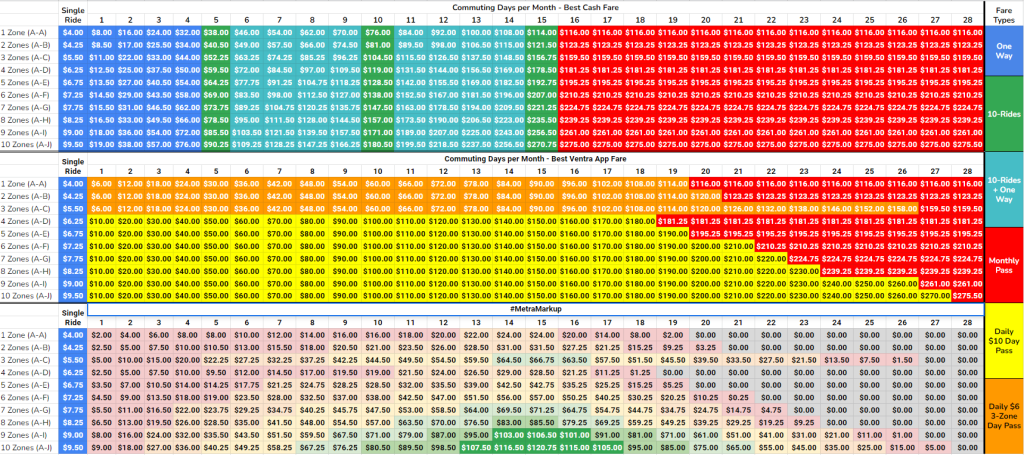

To this end, this post will attempt to identify a potentially-plausible phased approach to get Chicagoland from today to the regional rail network our region deserves. The service plans and proposals included herein are, of course, entirely unofficial: the CrossTowner regional rail proposal has always been, and continues to be, an exercise in imagining what could be rather than an official or professional regional plan. These plans have not been vetted by any of Chicagoland’s transit agencies, and rely exclusively on publicly-available materials and observations. Much further study and planning would be required before any implementation begins, but this post is an attempt to show how we could eat the proverbial elephant one bite at a time.

Before We Begin

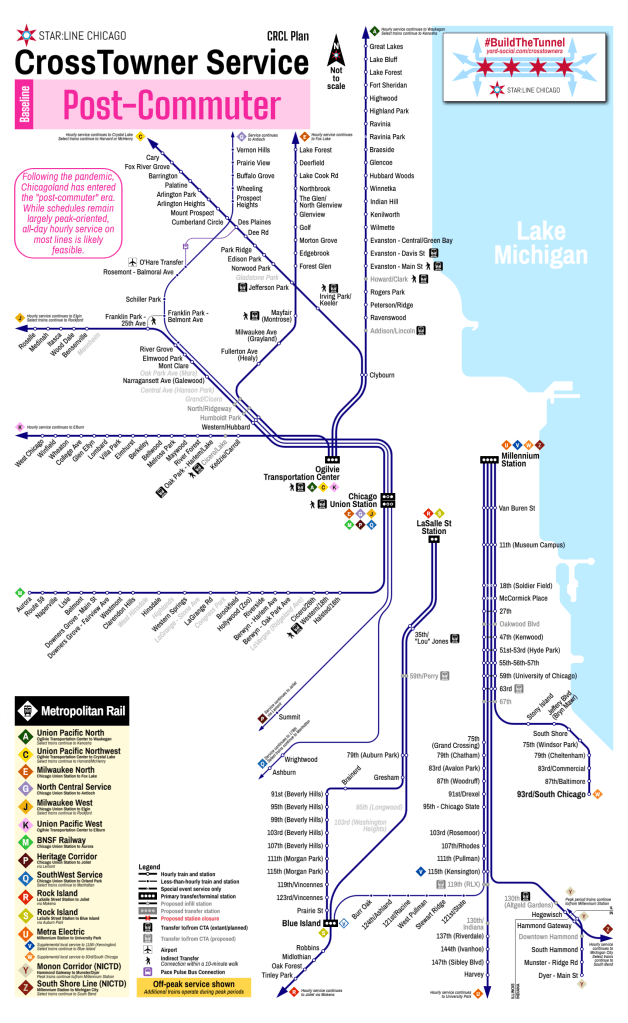

Some housekeeping before we get into the details: this post will rely heavily on maps that document different phased implementation components of the larger CrossTowner regional rail network vision. In some cases, the phases are irrelevant: some infill1 stations, for instance, could be constructed at any time (or not at all). In other cases, it may make sense to move certain components up or push them back based on cost, constructability, political realities, and so on.

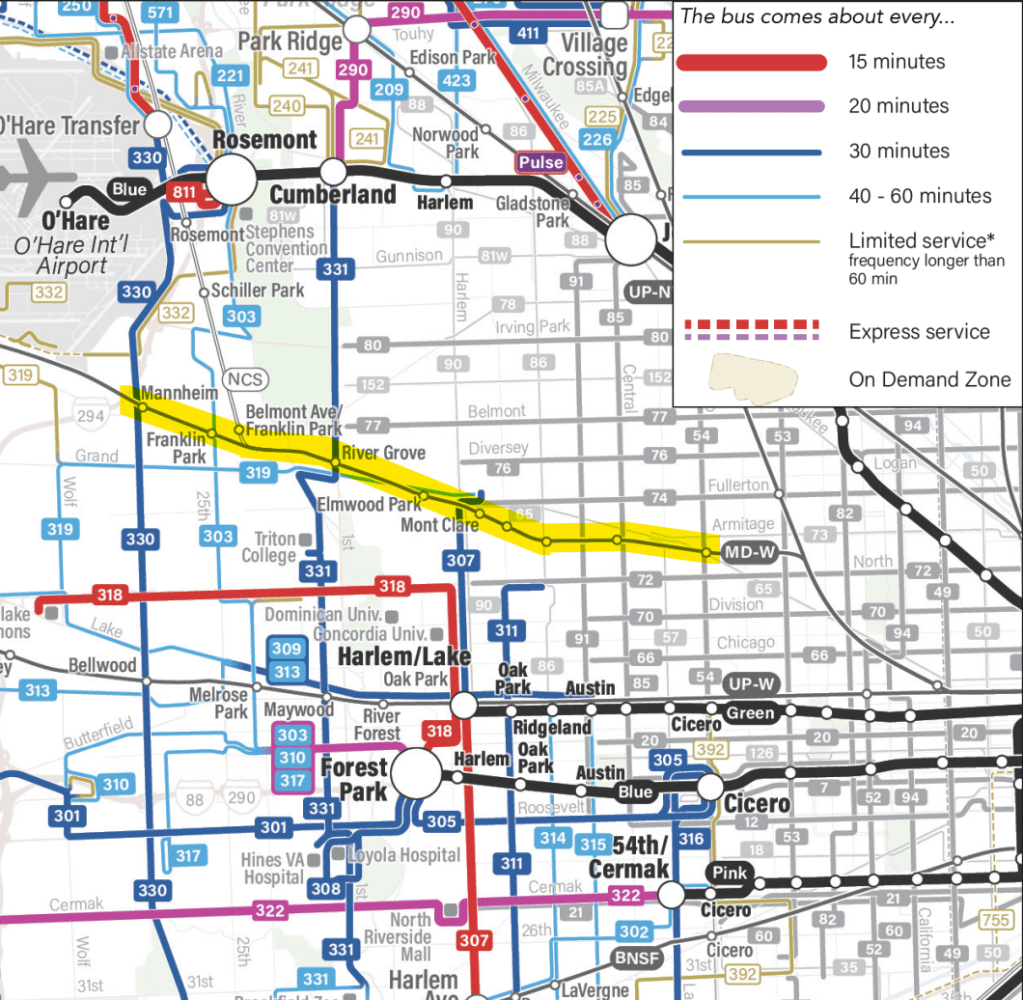

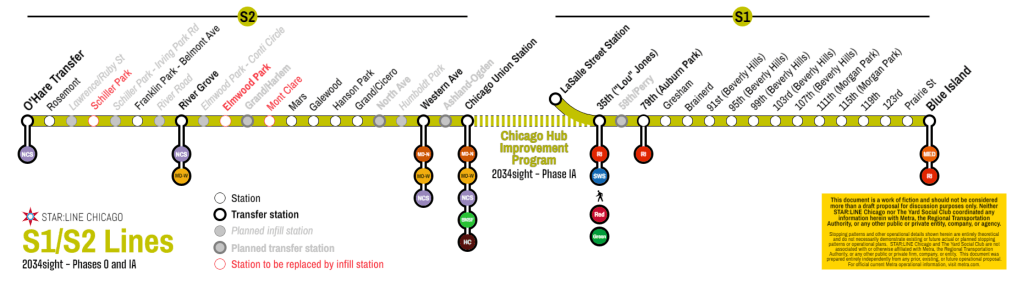

These maps also use a standardized “netgraph” approach to displaying service frequencies: each line represents one round-trip per hour. This allows an easier way to communicate average headways, or times between trains. Note, however, that these are averages: more detailed service planning would be required to determine more realistic schedules. Additionally, due to the realities of needing to balance local service with express service in some cases on shared tracks, perfectly-balanced headways all-day may not be entirely feasible.

Note that these maps all show proposed off-peak service levels. Additional trains would operate during peak periods, likely including Metra’s typical battery of suburban express services; these trains are not shown.

A quick mathematics cheat sheet:

- One line = one train per hour = 60 minutes between trains

- Two parallel lines = two trains per hour = 30 minutes between trains

- Three parallel lines = three trains per hour = 20 minutes between trains

- Four parallel lines = four trains per hour = 15 minutes between trains

- Five parallel lines = five trains per hour = 12 minutes between trains

- Six parallel lines = six trains per hour = 10 minutes between trains

- Eight parallel lines = eight trains per hour = 7.5 minutes between trains

Thinner lines indicate lines that operate less than hourly; these stations are shown “inverted” (a solid-colored station with a white border, rather than a white circle with a colored border). Additionally, lines in future phases are shown by their “Yard Social Standard” identification scheme that is also shown on other CrossTowner materials. The below “baseline” map provides a comparison to that scheme and the existing line naming system.

The Regional Rail Road Map

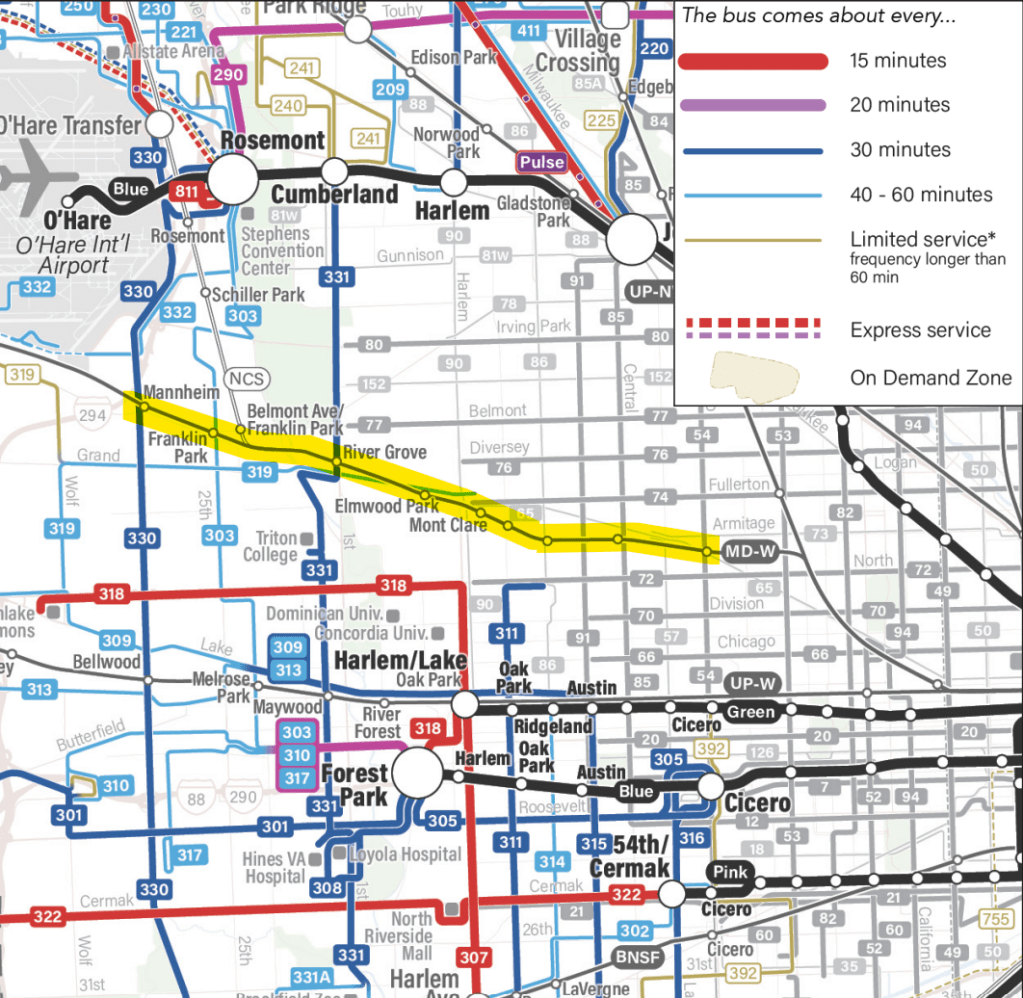

Baseline: The Post-Commuter Era

We begin with the “Post-Commuter” era: Metra has already committed to transitioning their fundamental operating model from “commuter rail” to “regional rail”. Preliminarily, this can be best summarized as “hourly everywhere”: while some level of peak-period focus is warranted based on present ridership, the larger goal is to provide bi-directional all-day service throughout the service area. At present, Metra has been actively moving towards hourly headways wherever possible.

Unfortunately, that is not feasible everywhere: freight conflicts at numerous locations on the Heritage Corridor and SouthWest Service, as well as some single-track chokepoints on the North Central Service, will make all-day hourly service challenging from an infrastructure perspective. Additionally, on most lines Metra remains at the whims of freight railroads that either control the lines outright or exercise a high degree of autonomy that prevents Metra from easily increasing service. These constraints are one of the primary reasons why Metra cannot easily add additional service, and they need to be a political priority for our region as the NITA era begins.

For the purposes of this post, let’s assume that they can be mitigated to some degree: Metra will need to continue to share tracks with freight traffic, and will need to ensure freight railroads can still reasonably operate throughout the day, but where freight traffic is lighter, Metra and the freights could come to some sort of agreement to add service.

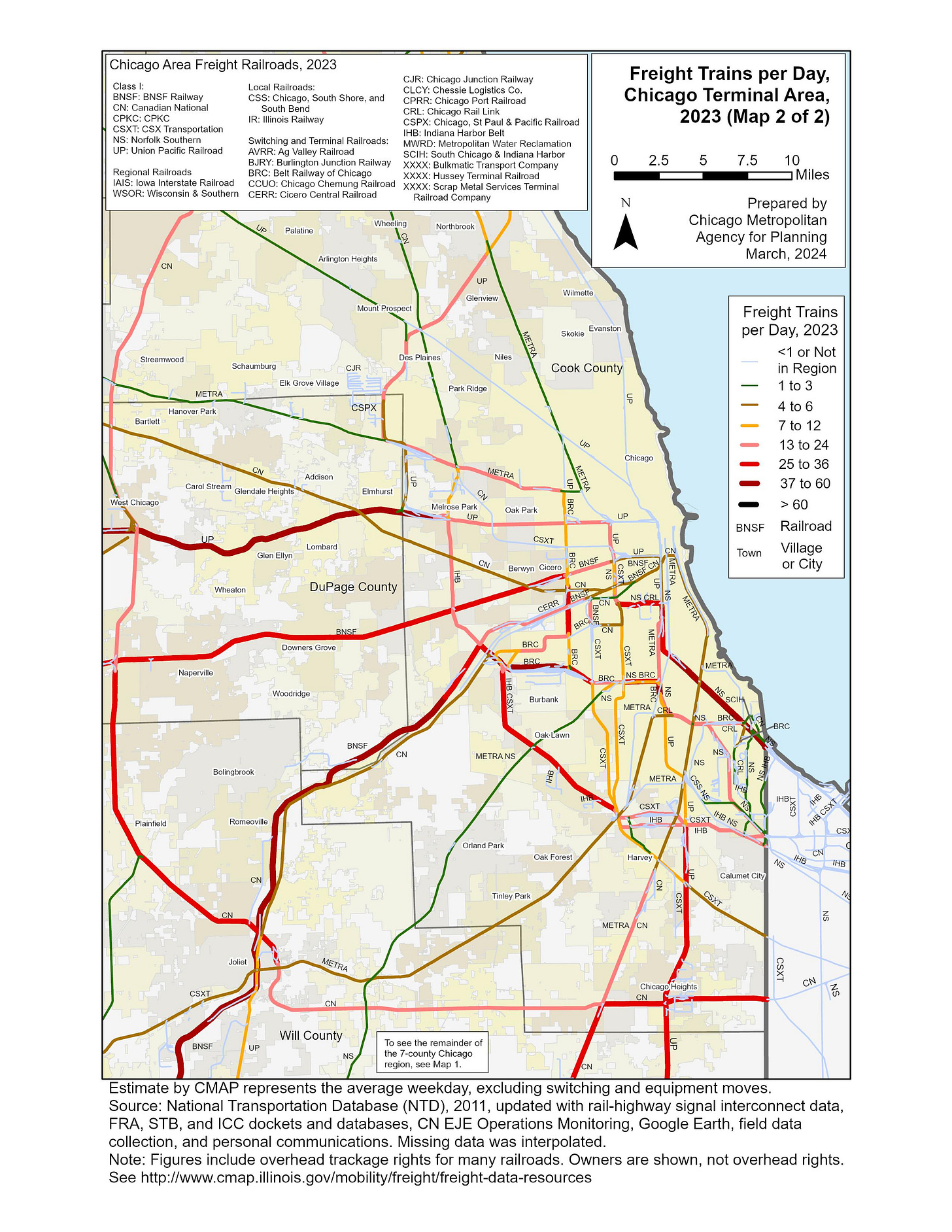

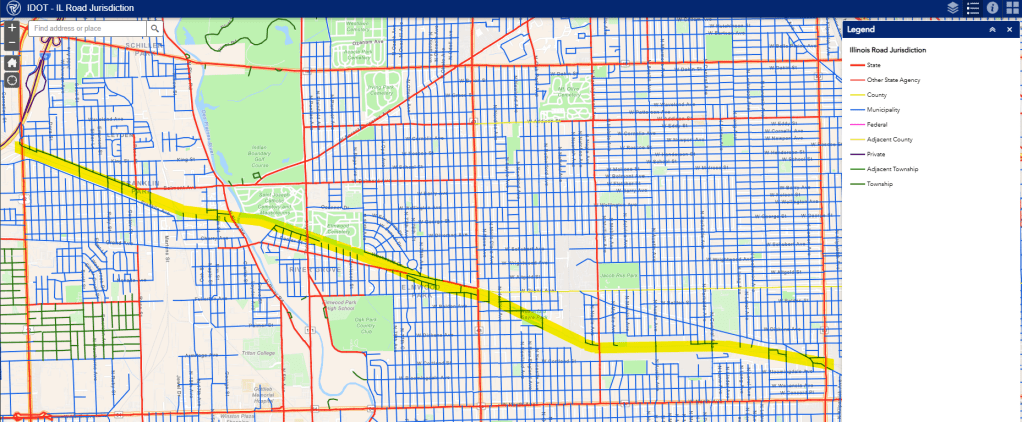

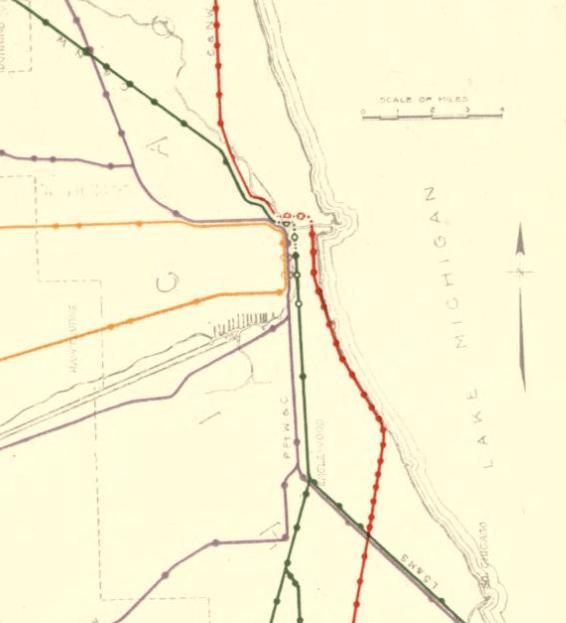

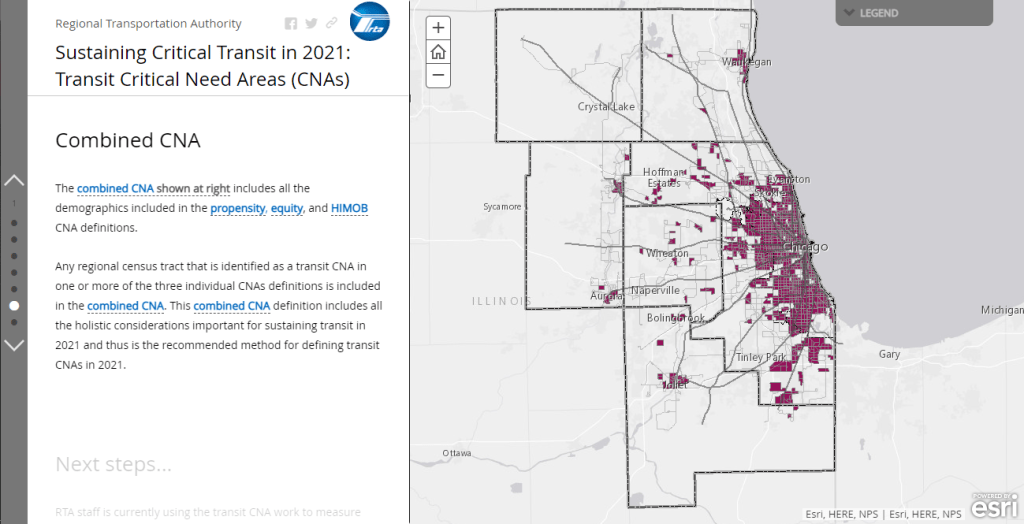

For reference, here is a recent CMAP freight rail volume map, as of 2023.

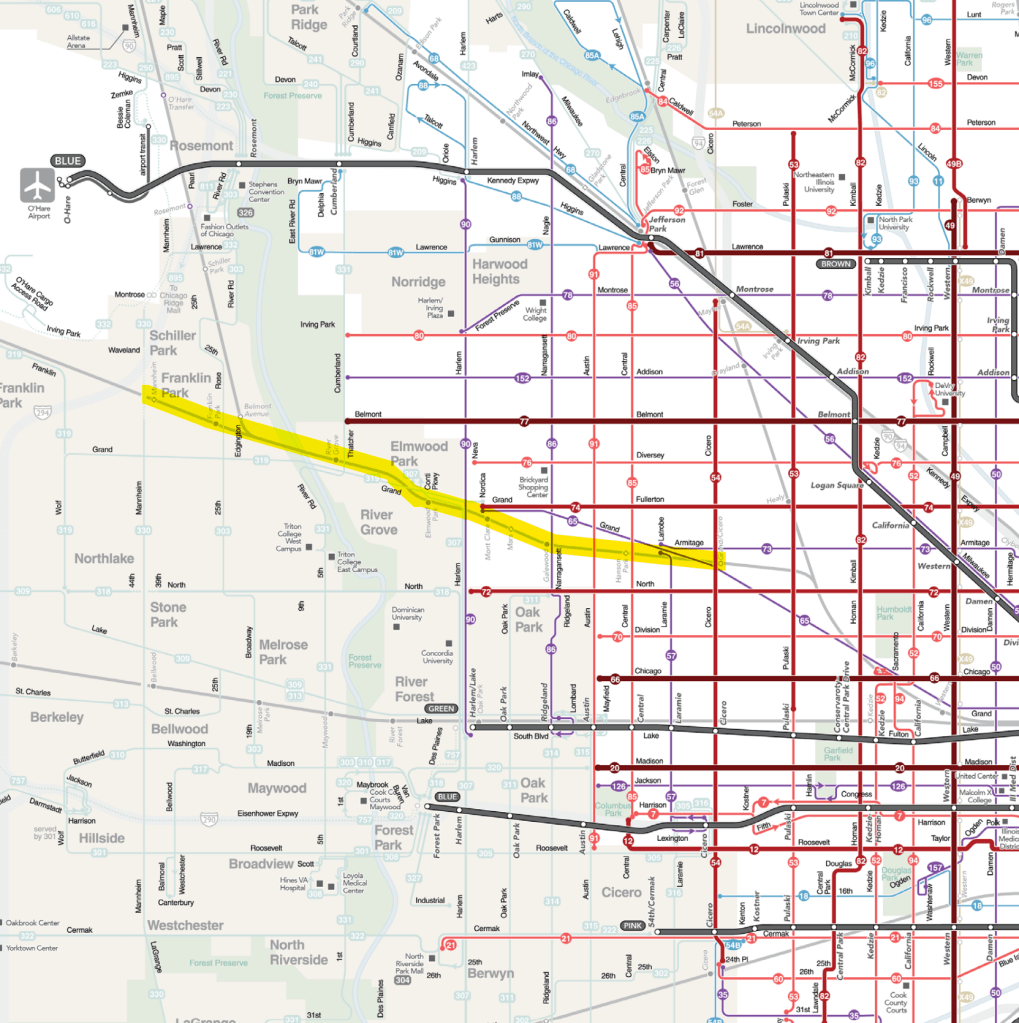

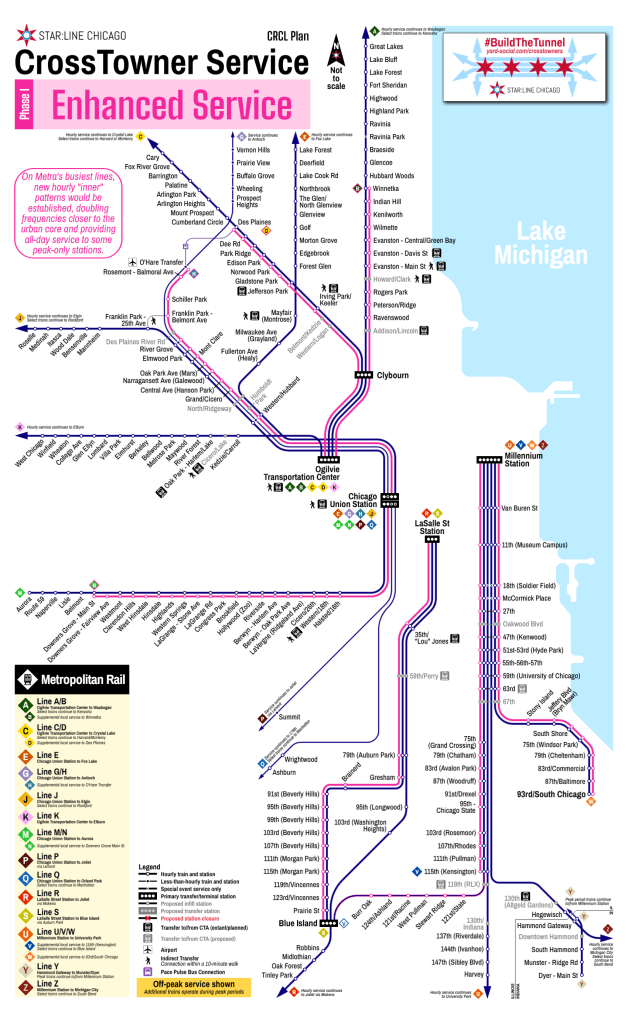

Phase I: Enhanced Service

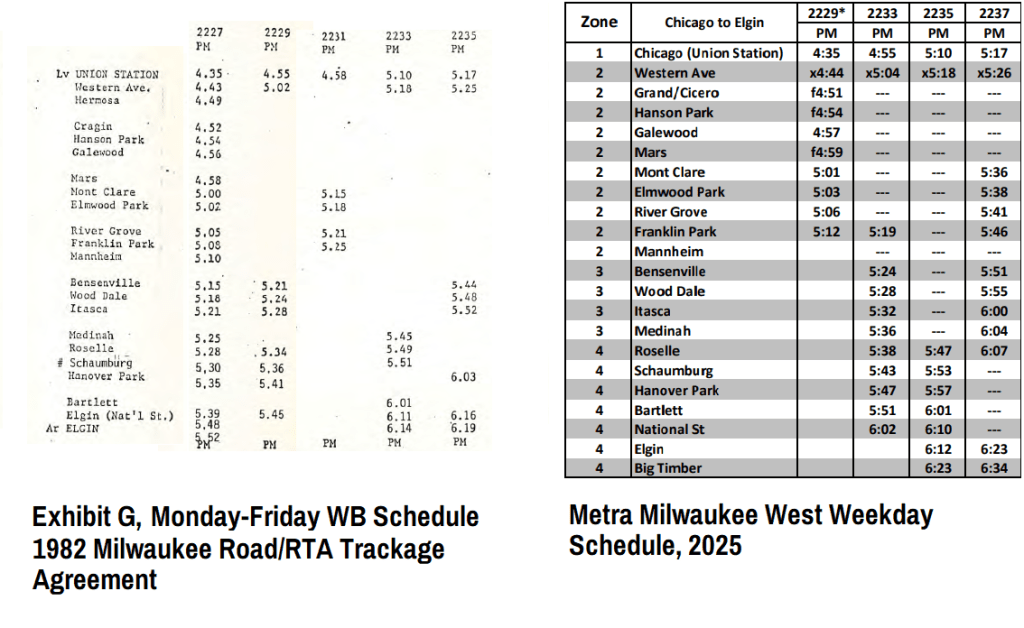

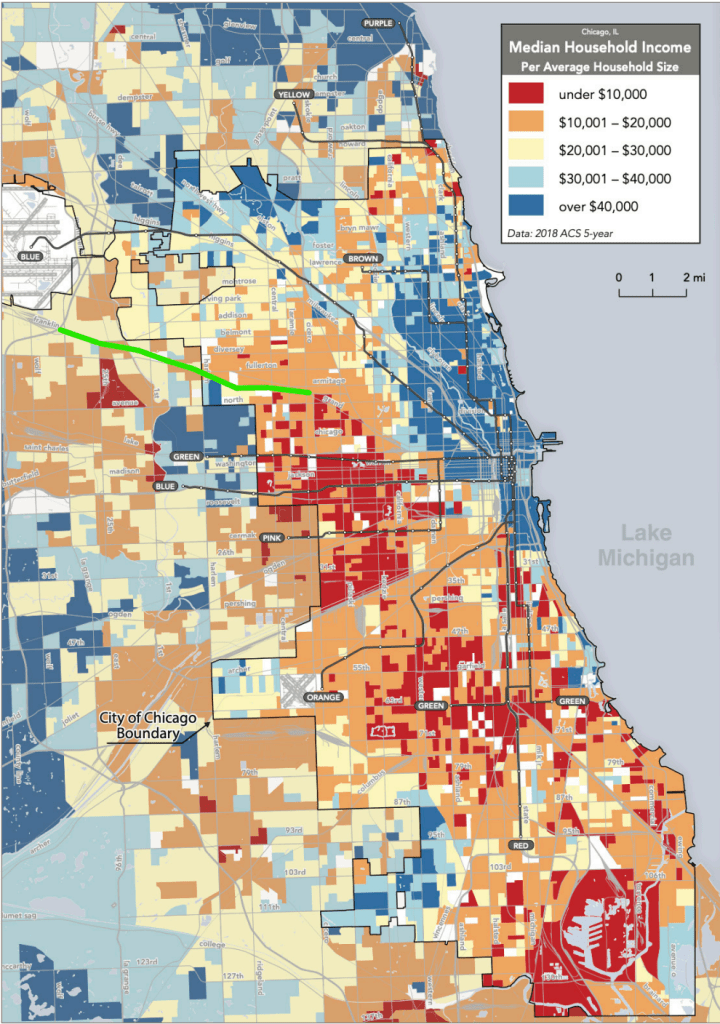

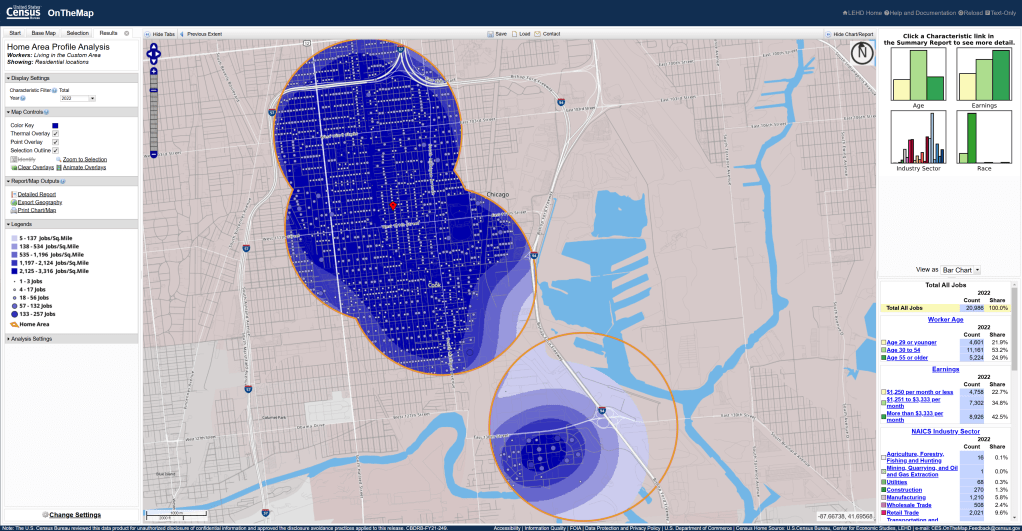

As Chicagoland takes concrete steps to move towards a proper “regional rail” paradigm, the first step would be adding additional trains to the central part of the region, where population densities are more supportive of increased service on some of Metra’s busiest routes. While “hourly everywhere” remains the goal for the region as a whole, supplemental service would be offered such that frequencies would improve to half-hourly closer to the urban core, while also beginning to provide all-day (hourly) service to some current peak-only stations, especially along the BNSF and Milwaukee West lines.

Supplemental hourly trains (to create half-hourly headways) would begin running on the Union Pacific North (“A/B”), Union Pacific Northwest (“C/D”), BNSF (“M/N”), Rock Island Beverly Branch (“S”), and Metra Electric South Chicago (“W”) lines. Supplemental trains would also operate on the Metra Electric Main Line and Blue Island Branch (“V”), to provide half-hourly frequencies north of Kensington and hourly service on the Blue Island Branch. Combined with half-hourly service on the South Chicago Branch, this would provide 15-minute service between Hyde Park and Millennium Station, not including Main Line (“U”) and South Shore Line (“Z”) express trains.

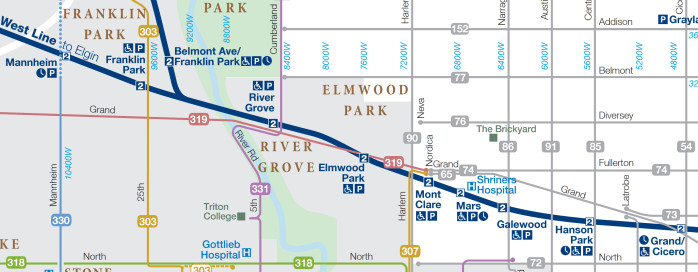

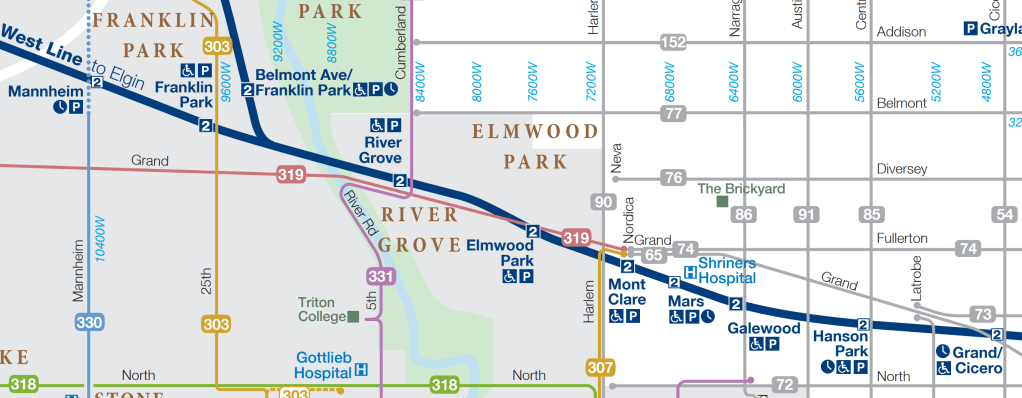

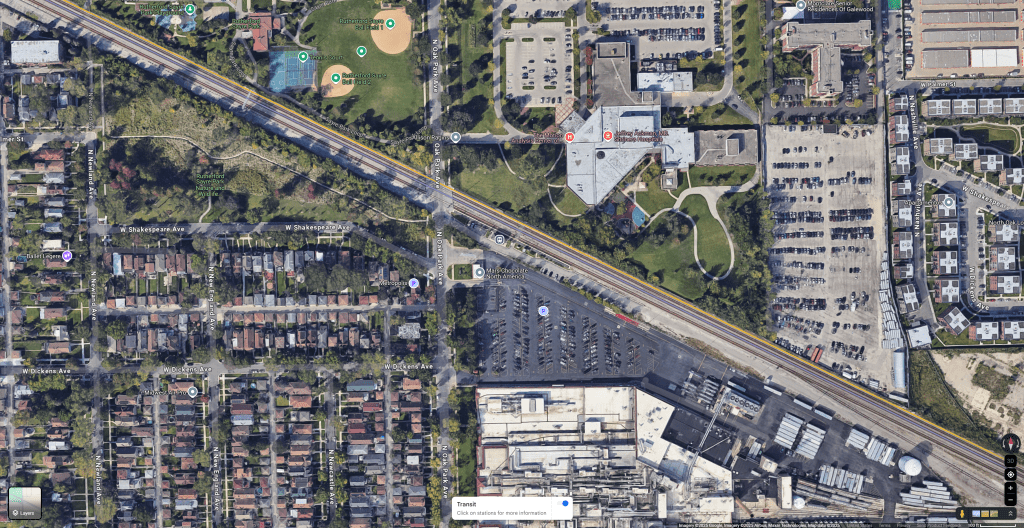

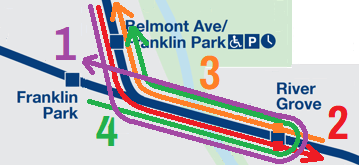

A “new” line would also be created: Line “H” would serve as the supplemental hourly local pattern combining Milwaukee West and North Central Service stations between Chicago Union Station and O’Hare Transfer. Line “H” would also relieve the NCS of the need to make stops at Franklin Park, Schiller Park, and Rosemont, speeding trains up from the northern suburbs as well as speeding up express trains to O’Hare.

Following Phase I, most Metra stations in Chicago and some inner suburbs would be able to provide half-hourly service all day long, with only seven additional trains per hour region-wide.

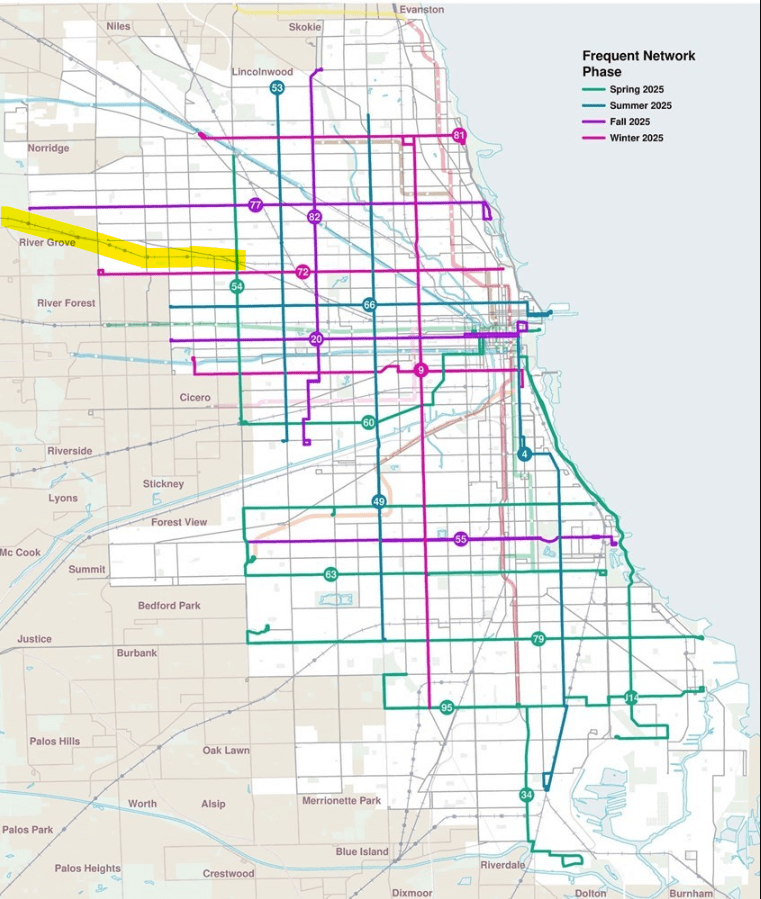

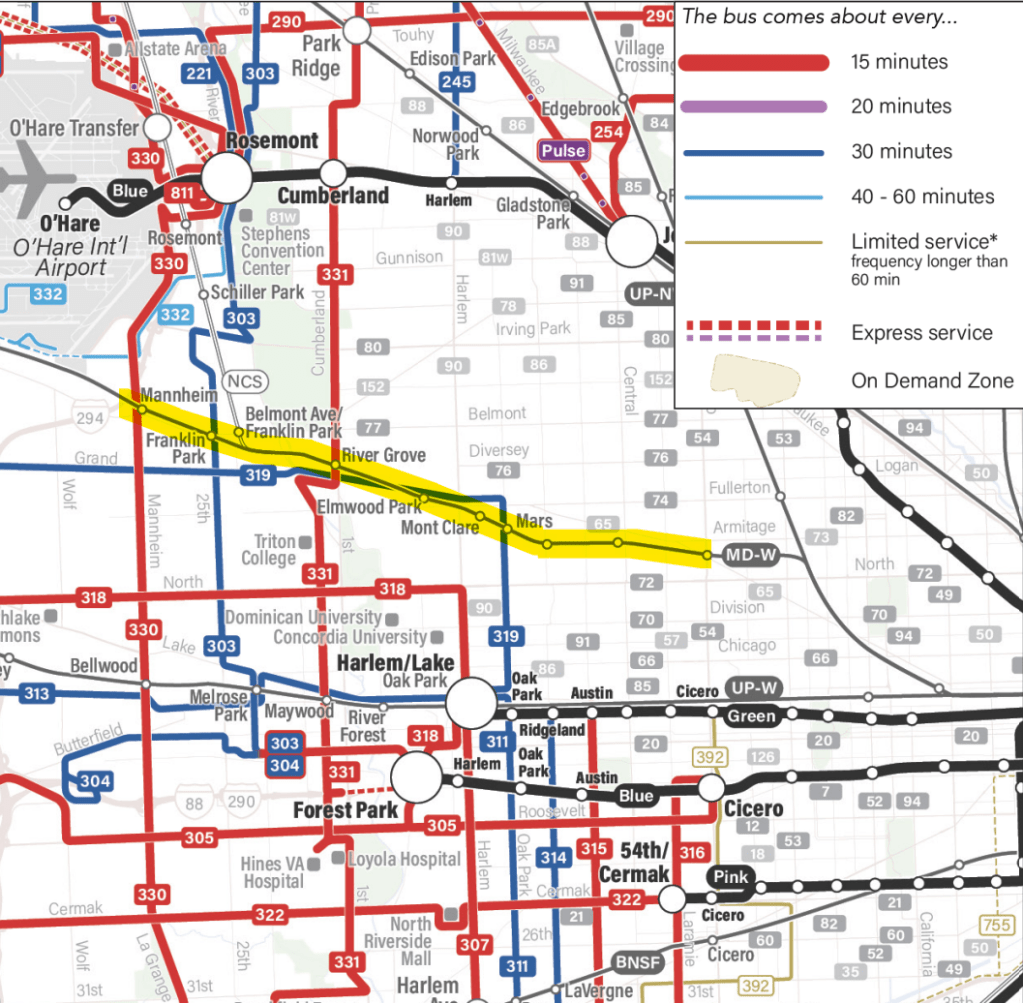

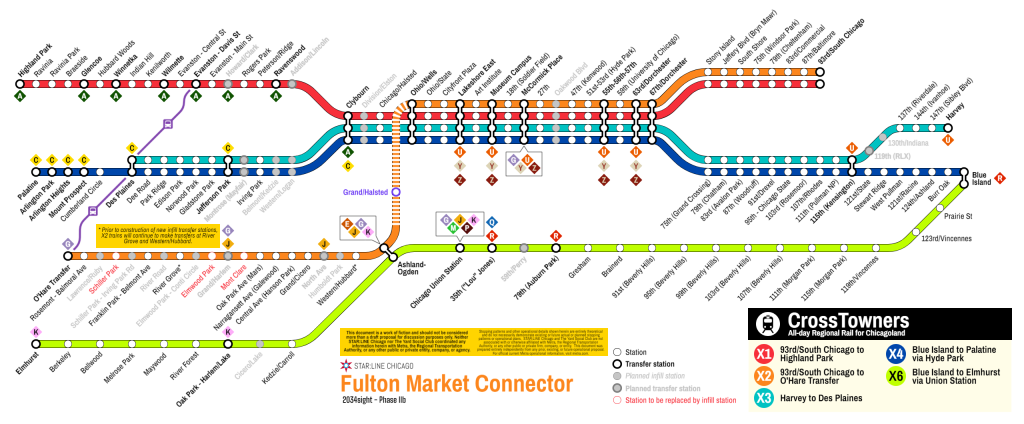

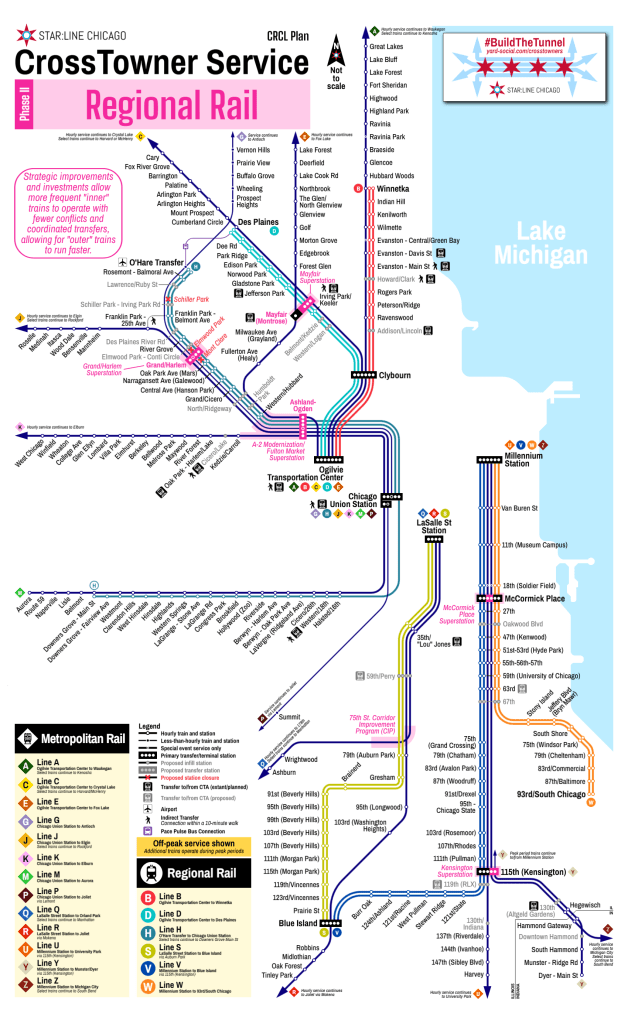

Phase II: Regional Rail

Following the Enhanced Service in Phase I, Phase II would take a stronger step towards a proper “regional rail” network. At a high level, the goals of Phase II are to separate “inner” supplemental service trains from “outer” suburban trains, allowing the latter to run express all day long.2 To allow this, strategic station investments are needed to create better transfer stations — “superstations” — that allow “inner” and “outer” trains to coordinate service, maintaining connectivity throughout the region while speeding up express services. The six “regional rail” lines also now have their own distinct identification, and would likely also use a more modern rolling stock similar to Metra’s forthcoming Stadler FLIRT fleet.

Phase II has six primary infrastructure improvements:

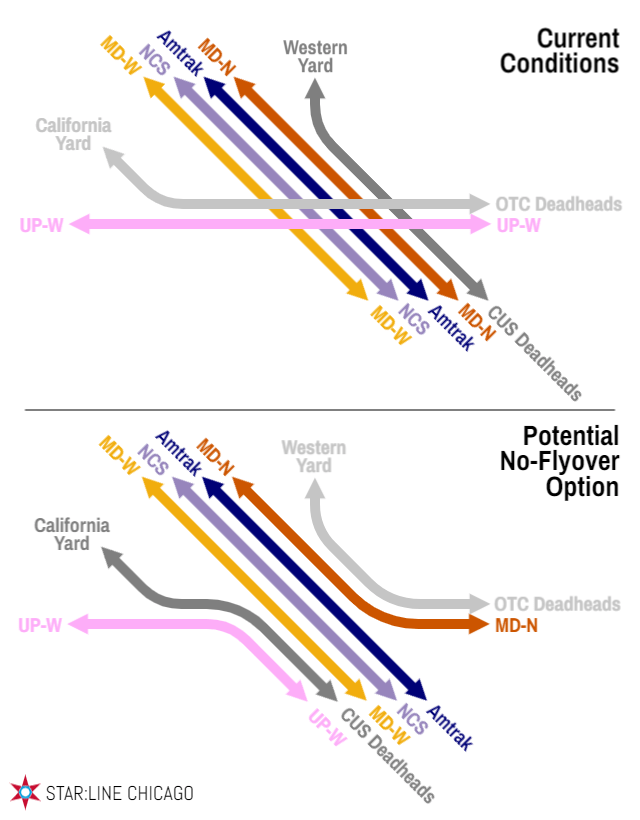

- A-2 Modernization and Fulton Market Superstation: Perhaps the most important project in this phase, this effort would reorganize Metra’s complicated A-2 interlocking on the West Side near Western Avenue, minimizing crossing conflicts by re-routing Line “K” (UP-W) trains into Chicago Union Station and Line “E” (MD-N) trains into Ogilvie Transportation Center. This reconfiguration would almost certainly be required before increasing frequencies between Chicago Union Station and O’Hare. This phase would also include a new Fulton Market Superstation to allow transfers and connections, as well as serve a burgeoning part of the city. (This project has been on Metra’s radar for a while.)

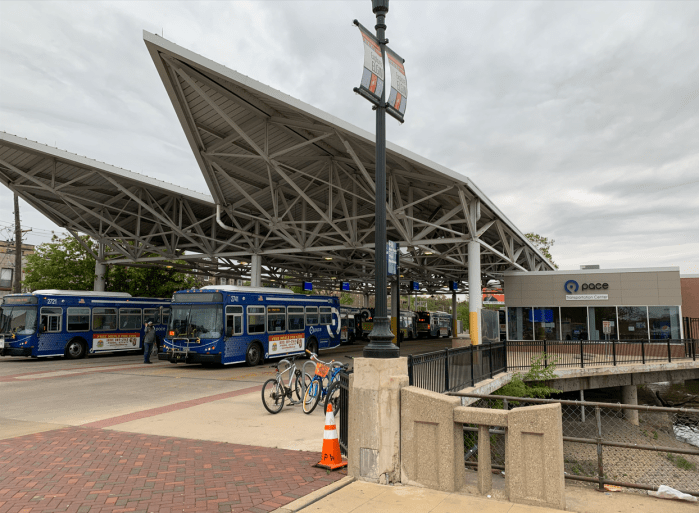

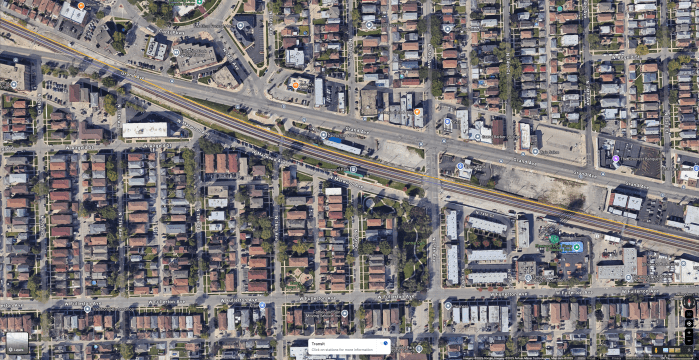

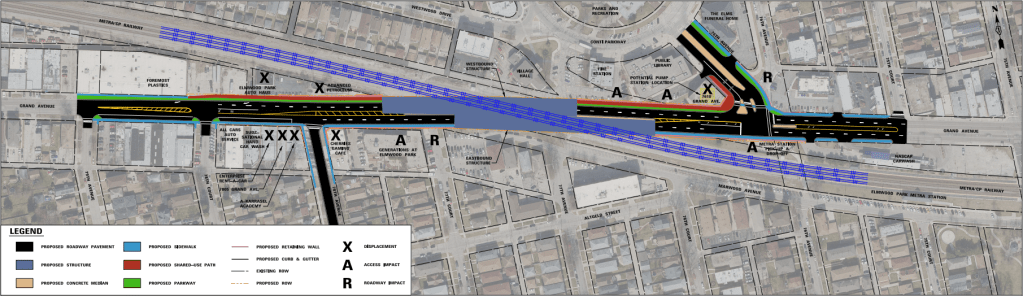

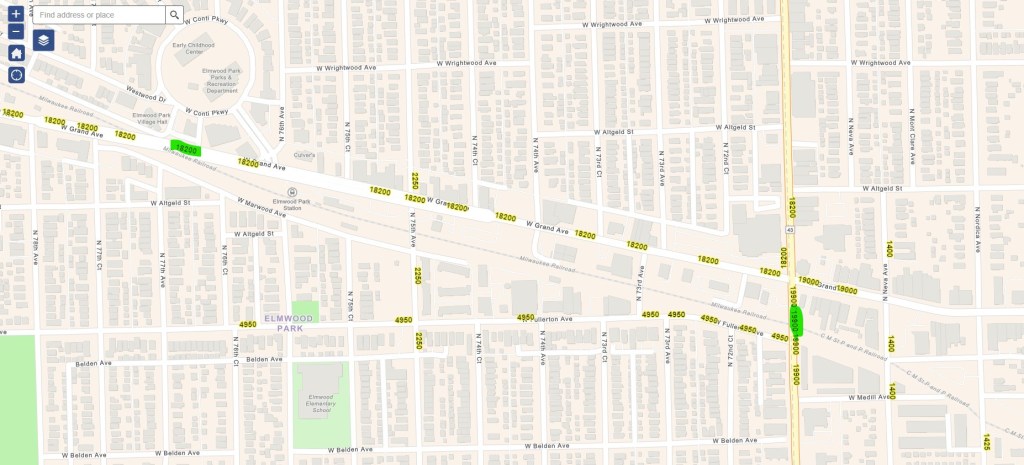

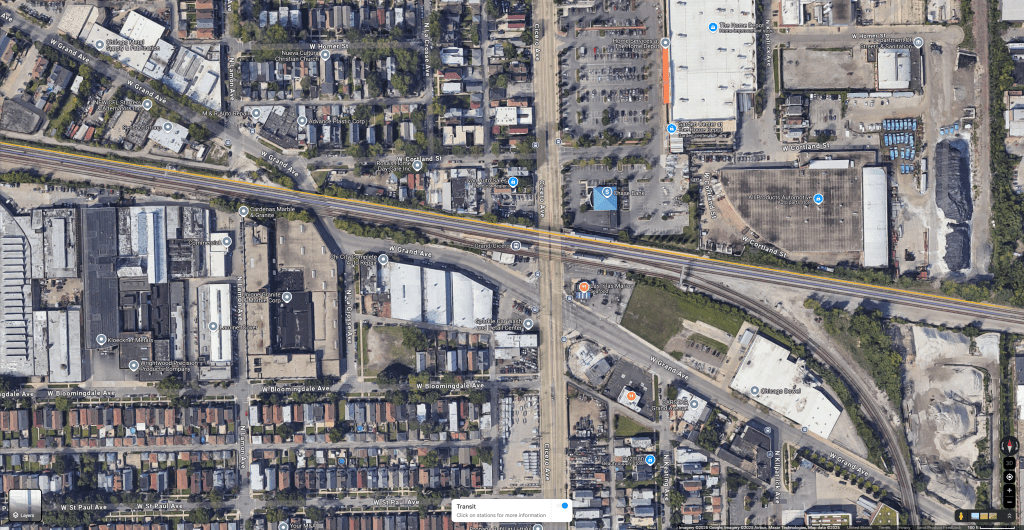

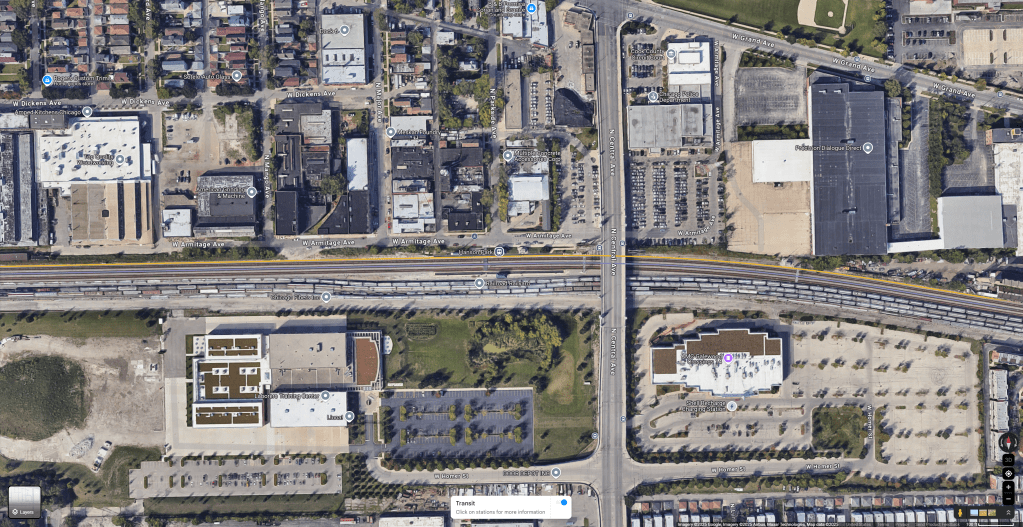

- Grand/Harlem Superstation: A station consolidation on the Northwest Side would create a contiguous Harlem Avenue bus corridor that connects express and local rail service to O’Hare to two other Metra lines (UP-W at Oak Park and BNSF at Harlem Avenue) as well as two3 CTA ‘L’ lines (Green Line at Harlem/Lake and Blue Line at Harlem-Congress). The full CrossTowner vision includes this bus route as a Pace Pulse corridor that would extend to Summit, then east on Archer/55th to the Orange Line ‘L’ terminal at Midway Airport.

- Mayfair Superstation: A new station on Line “C/D” (UP-NW) that would connect with the existing Line “E” (MD-N) Mayfair station and the existing Blue Line Montrose station. While the UP-NW also has Blue Line connections north and south of Mayfair, creating a unified Northwest Side superstation could anchor a future Brown Line western extension, as well as create far easier Amtrak connections between Hiawatha/Borealis/Empire Builder trains and O’Hare Airport via the Blue Line. Thinking far further into the future, a Mayfair superstation could also allow for reuse of the Weber Spur as a transit artery, as well as bookend a northern Cicero Avenue transitway.

- 75th Street Corridor Improvement Program (CIP): Another project that has been on the books for years, the 75th Street CIP would allow Line “Q” (SWS) trains to connect to LaSalle Street Station instead of Chicago Union Station while also bypassing key freight bottlenecks. While this project would not have a direct impact to the “regional rail” lines, it would be a significant improvement that makes hourly SWS service more feasible.

- Kensington Superstation: On the Far South Side, the existing 115th (Kensington) station would be (re-)expanded to (once again) allow for NICTD trains to make stops, supplementing the local/express patterns of the Metra Electric. Additionally, with NICTD operating the new Monon Corridor as an off-peak shuttle operation between Dyer and Hammond Gateway, Monon (Line “Y”) shuttle trains could be extended to the Kensington Superstation, doubling frequencies to Hegewisch.

- McCormick Place Superstation: To better serve a major trip generator, as well as to provide another local/express transfer location along the Metra Electric, additional platforms would be added at McCormick Place in advance of future phases and service expansions. These new platforms would also allow special-event services on the express patterns to more easily serve McCormick Place without interfering with all-day local services.

On the North Side, these improvements, combined with three additional round-trips per hour, would allow for the busy “A” (UP-N) and “C” (UP-NW) lines to run express to speed up trips from the north and northwest suburbs, and on the West Side, local Line “H” trains could run twice an hour between Chicago Union Station and O’Hare Transfer to provide more robust all-day transit service connecting working-class neighborhoods to the region’s two largest job centers. The added hourly Line “H” train could also utilize the single existing thru-track at Chicago Union Station to replace the “N” BNSF supplemental pattern, creating a single-seat trip between Metra’s busiest line and O’Hare. Furthermore, with half-hourly service, Line “G” (NCS) trains could skip more stations, providing an early “O’Hare Express” operation between Chicago Union Station and the airport.

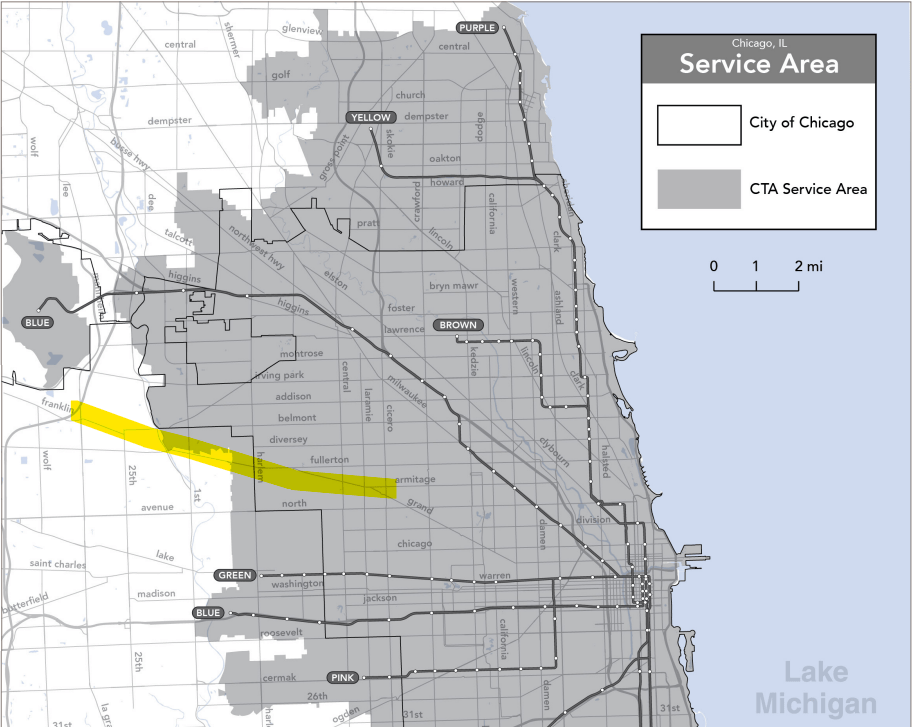

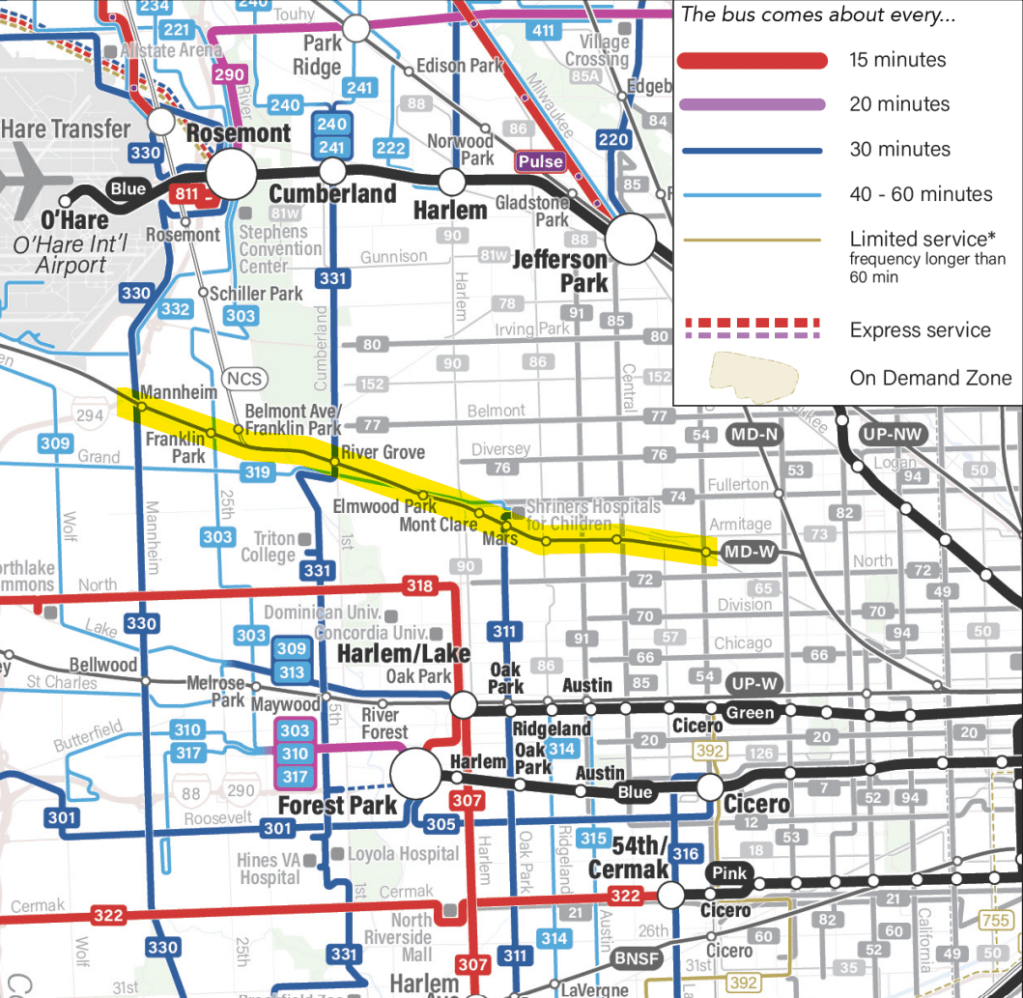

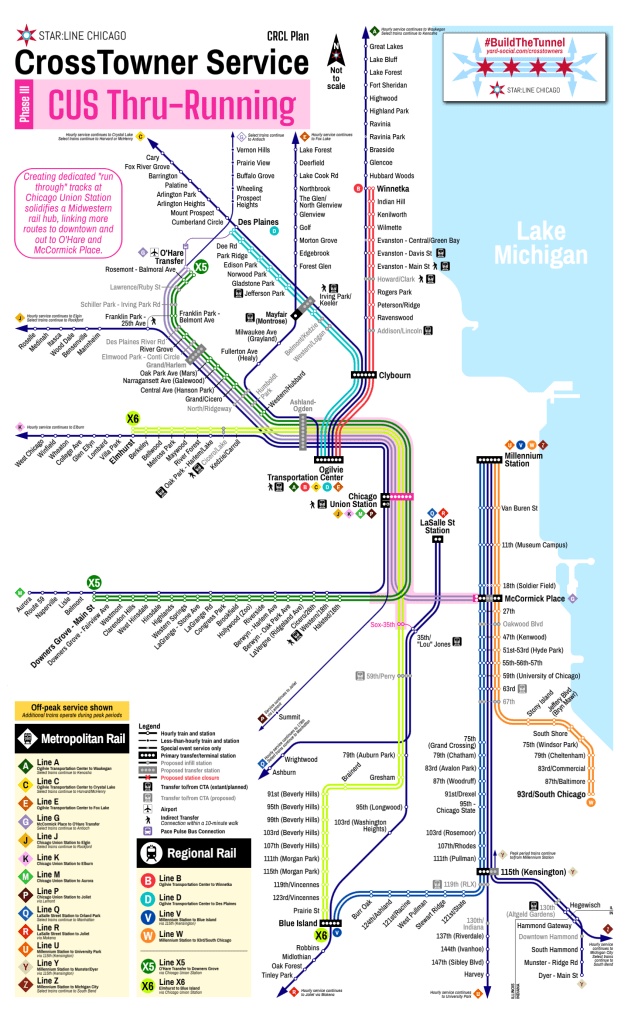

Phase III: CUS Thru-Running

The larger regional CrossTowner network starts to take shape in Phase III, when dedicated thru-running tracks at Chicago Union Station are constructed. This improvement can allow for proper thru-running operations at Chicago Union Station for regional rail service at higher frequencies. Combined with Amtrak’s Chicago Hub Improvement Program (CHIP), three primary routes could be implemented:

- X5: Building on the work of Phase II, the other hourly Line “H” train would also be thru-run to Downers Grove Main Street and rebranded as the X5 CrossTowner. This change would allow Line “M” (BNSF) trains to run essentially express east of Downers Grove, with stops only at Hinsdale, LaGrange Road, Harlem Avenue, Cicero, and Western.

- X6: To create a future unified hub at Chicago Union Station, Line “S” (Beverly Branch) trains would turn off of the Rock Island District to connect with the vacated4 SouthWest Service tracks, run through Chicago Union Station, and provide regional rail service along Line “K” (UP-W). The CrossTowner vision suggests this connection be made through the parking lots of Rate Field, but several alternative options could be feasible and require further study. This route would be rebranded as the X6 CrossTowner.

- O’Hare Express (Line “G”): Thru-running Chicago Union Station, combined with fewer stops between downtown and O’Hare for Antioch-bound trains, and improving the St. Charles Air Line (SCAL) bridge over the Chicago River, creates the opportunity to operate an oft-desired airport express service between the McCormick Place Superstation, downtown, and O’Hare. Unlike other airport express operations, however, this would functionally be just an extension of Line “G” (NCS) suburban trains.5 6 While not officially a CrossTowner line, this service would be an important component of the larger system and would provide single-transfer connections from the Metra Electric lines to Chicago Union Station and O’Hare prior to the construction of the tunnel.

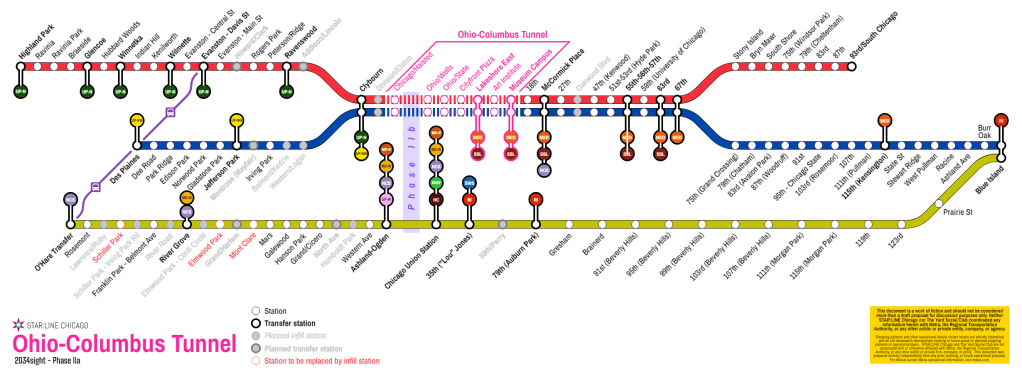

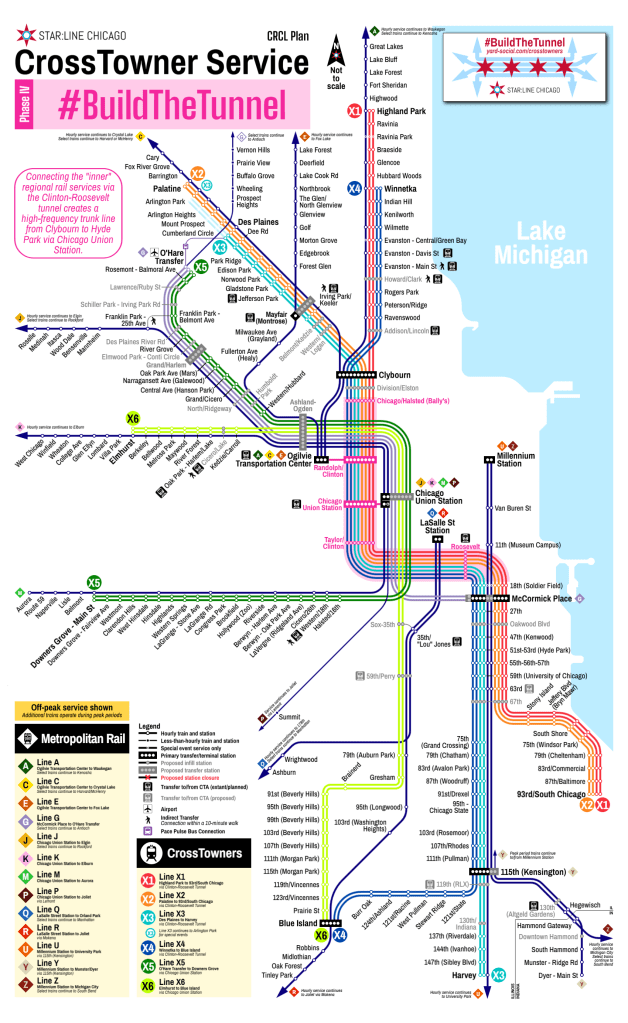

Phase IV: #BuildTheTunnel

By the time we get to building the tunnel, operationally it ends up being an extremely straightforward enhancement. The tunnel gets built under Clinton Street and Roosevelt Road, and each of the four remaining regional rail lines (“B”, “D”, “V”, and “W”) simply continue through the tunnel and out to regional rail lines on the other side as CrossTowners. Doing so halves headways on the rest of the regional rail network, while expanding half-hourly service further out into the suburbs. Within the tunnel itself, and indeed down the entire “trunk” between Clybourn and Hyde Park, CrossTowner trains now operate every 7.5 minutes, and every 15 minutes as far as Kensington, South Chicago, Winnetka, and Des Plaines.

The tunnel would greatly enhance regional intermodal connectivity with stations at Randolph/Clinton (connecting to Green and Pink Line ‘L’ trains at the existing Clinton/Lake station and Metra trains at Ogilvie), Chicago Union Station (connecting to Blue Line ‘L’ trains at the existing Clinton/Congress station as well as Amtrak, Metra, X5 and X6 trains at the station), Taylor/Clinton (to seed a new transit-oriented development neighborhood), and Roosevelt (connecting to Red, Orange, and Green Line ‘L’ trains at the existing Roosevelt station).

The core CrossTowner network is now complete.

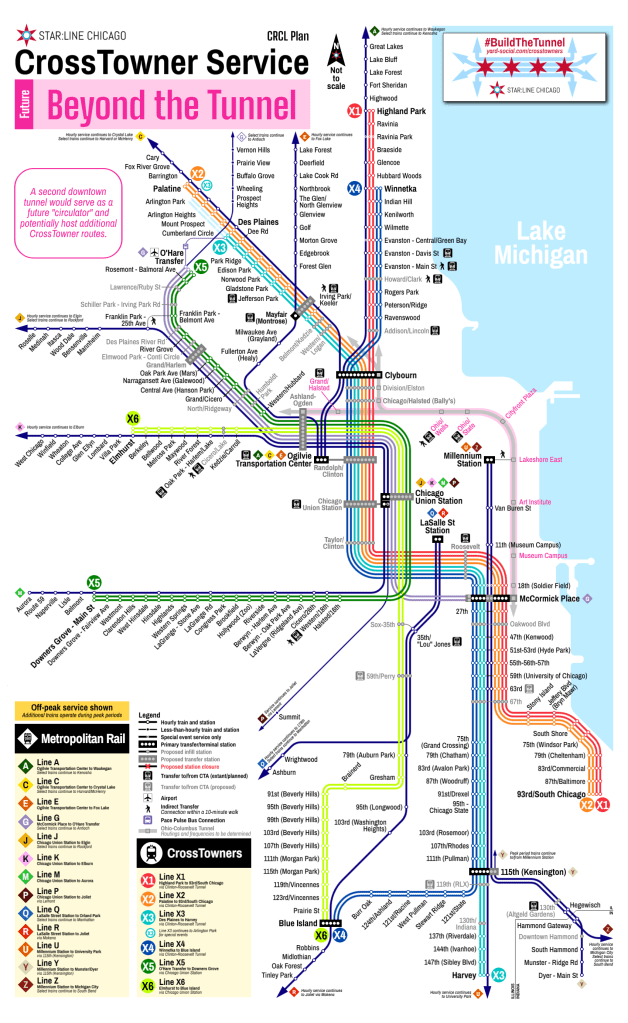

Beyond The Tunnel

While the initial vision would be complete, that doesn’t mean there wouldn’t be additional opportunities for expansion. With no freight conflicts on the Metra Electric District, additional regional rail routes could be added later; more frequent service to O’Hare, or expanding regional rail to the Milwaukee North, or entirely new services could be added in the future. The original 2034sight Plan calls for a tunnel under Ohio Street and Columbus Drive, a corridor that remains ideal for additional high-frequency, high-capacity transit options to serve River North, Streeterville, and Lakeshore East. This alignment could also provide single-seat trips from the Far South Side to O’Hare more feasibly, and closer to downtown the Ohio-Columbus tunnel is bookended at each end by “superstations” to provide universal connectivity between lines as needed. Rather than precluding these service alternatives, the CrossTowner vision is intentionally open-ended and forward-compatible for the continued growth of Chicagoland’s transit network.

The time is now

As the new Northern Illinois Transit Authority (NITA) launches this summer, Chicagoland transit is in a position to not only survive but to thrive on regional coordination, integration, and bold visions for the future. Nothing worth having is ever easy, but CrossTowner regional rail can be the bold, achievable, pragmatic vision Chicagoland needs to once again shoot for the stars.

It’s time to unlock our regional potential. It’s time for regional rail.

And it’s time to #BuildTheTunnel.

- Justification for individual infill stations are generally not included in this post, but additional information will eventually be posted somewhere. These posts are long enough without getting truly into the weeds. ↩︎

- This operating paradigm was recommended as part of CMAP’s Plan of Action for Regional Transit (PART) report development following the pandemic (pages 23-27). ↩︎

- Ideally three in the more distant future with a Pink Line extension to North Riverside. ↩︎

- Metra operations would have been moved off of this segment following completion of the 75th Street CIP, but Amtrak and occasional freight traffic would still likely use portions of the route. ↩︎

- Amtrak could plausibly extend Midwest intercity trains to O’Hare on the same routing; however, there is potential for that to be a net-negative at a local Chicagoland level if that operation would come at the cost of more frequent suburban service on the NCS. ↩︎

- It is not shown on these maps, but O’Hare Express (Line “G”) trains could also serve the proposed One Central megaproject near 18th Street in lieu of that project’s proposed reverse-branching of the BNSF. ↩︎