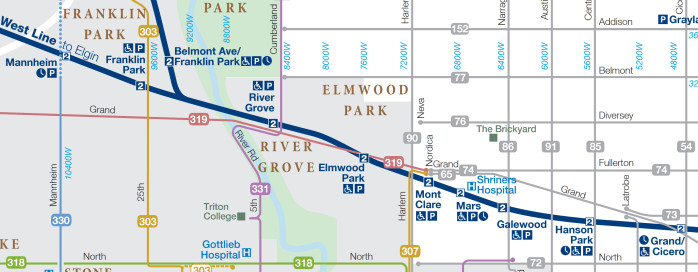

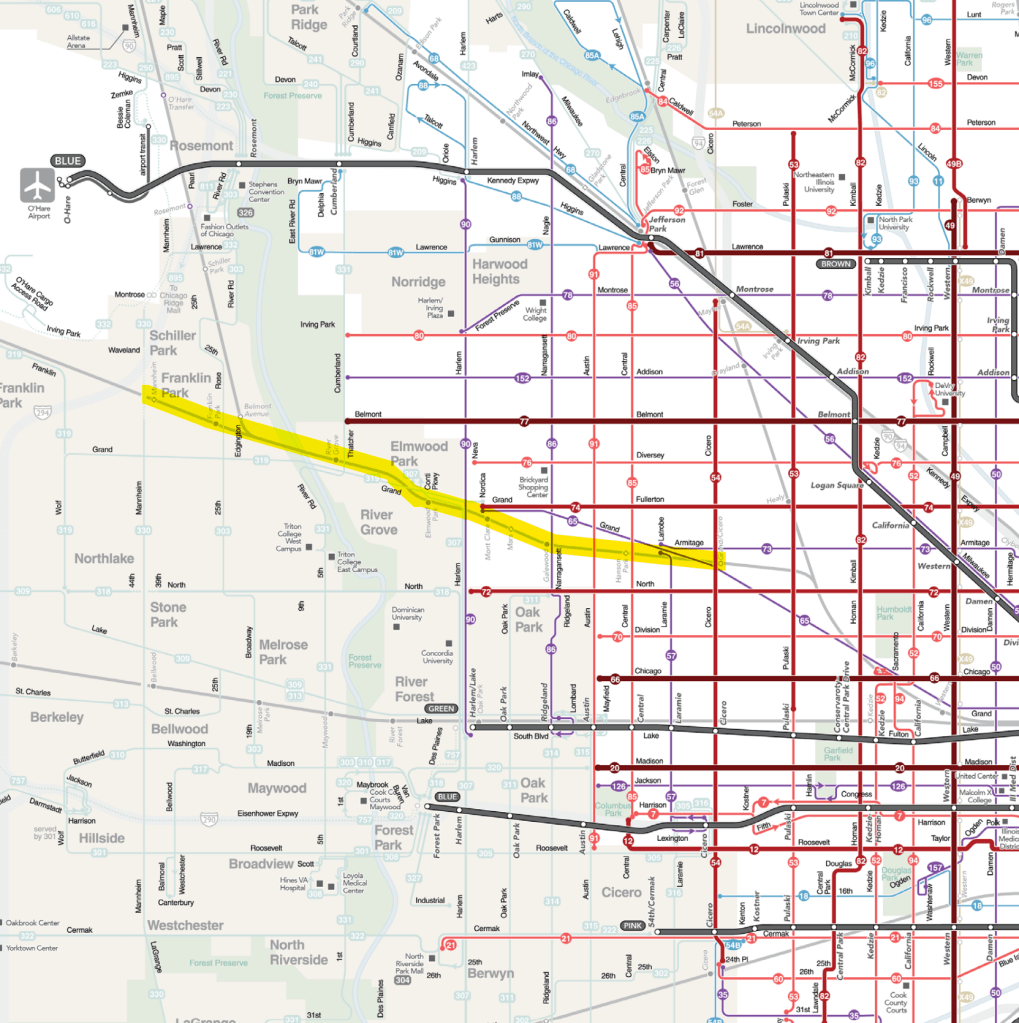

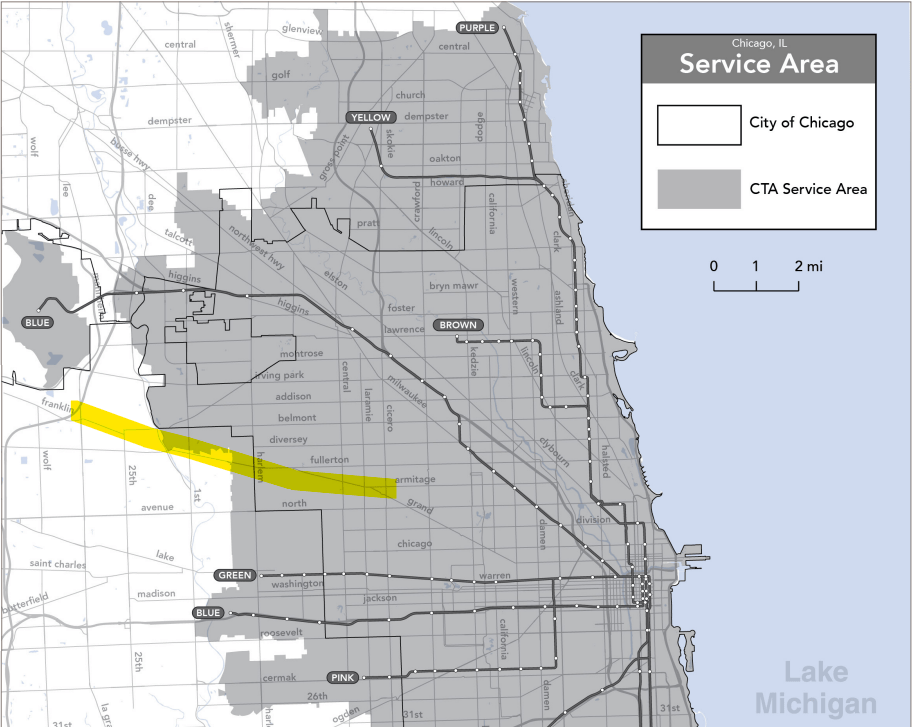

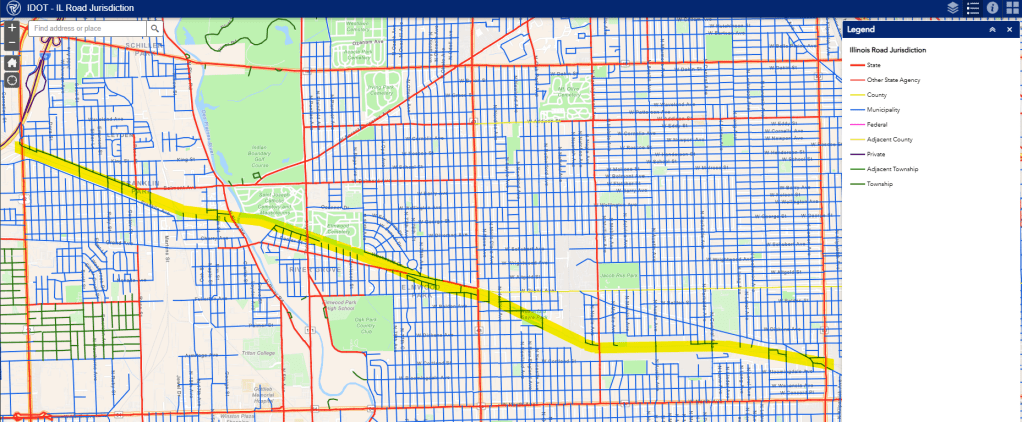

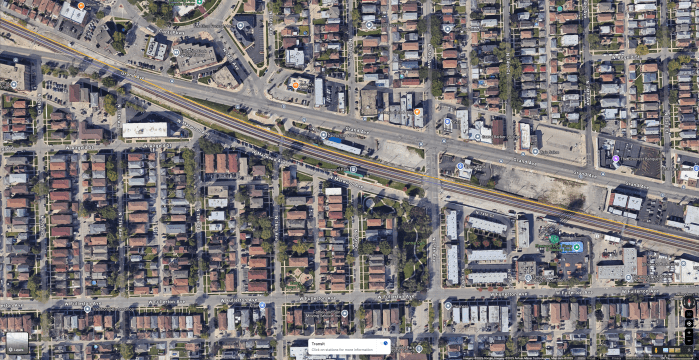

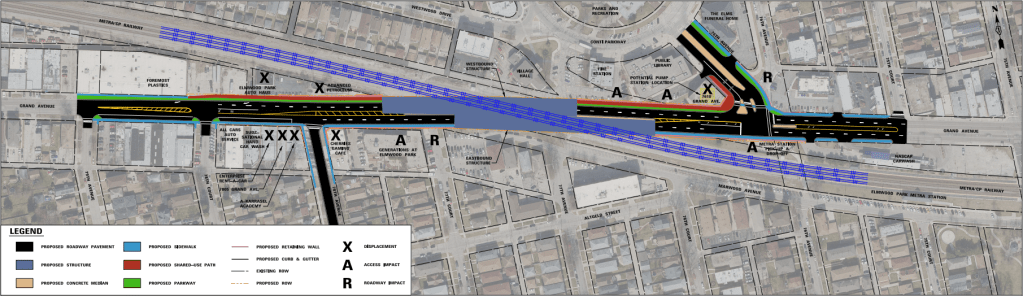

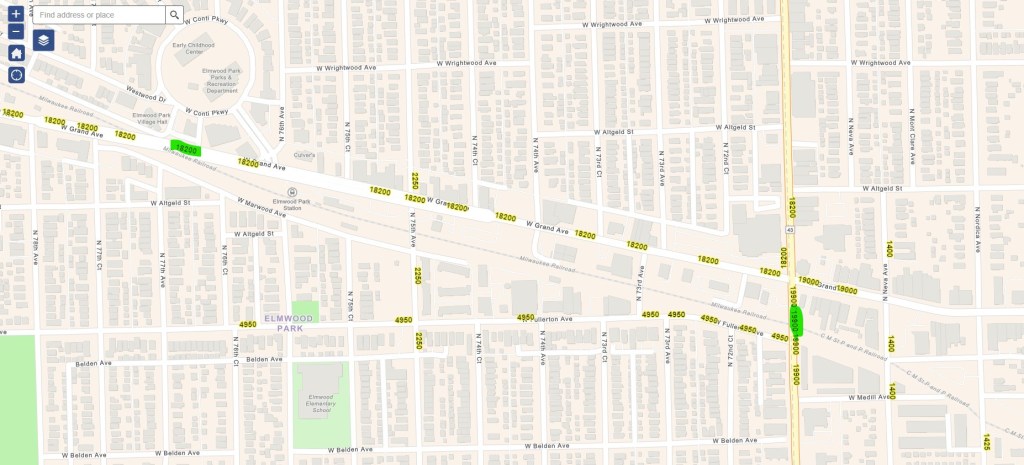

Over the past few weeks, this blog has explored what we’ve been calling the “Grand Corridor”, what should be a high-performing intermodal transit corridor straddling Chicago’s Northwest and West Sides as well as suburban Cook County that, ideally, could connect these working-class neighborhoods to Elgin, O’Hare, and the Loop with fast and frequent transit service, but due to Chicagoland’s byzantine, balkanized approach to transit operations and planning, result in only modest plans that fail to fully leverage this incredible asset.

However, it is the editorial policy of this blog that it does not offer criticism without also offering potential solutions, so to conclude this series, this post will detail a governance proposal to address some of these challenges and set the groundwork for a more efficient, more effective option to better position Chicagoland to operate and build a proper 21st-Century transit network that better levels the regional playing field, streamline processes, and break down harmful silos of governance, all without throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater.

If you’re reading this, there is an extremely high likelihood that you are already at least somewhat familiar with two primary pieces of legislation working their ways through the Illinois General Assembly down in Springfield that would both address transit governance issues in Northeastern Illinois: the Metropolitan Mobility Act, supported by the Partnership for Action on Reimagining Transit, which would dramatically transform our governance model by merging the RTA, CTA, Metra, and Pace into a single agency; and a more modest reform bill (that would simply delegate to the RTA some additional limited powers to oversee the three service boards) colloquially known as “the labor bill” in honor of the United We Move labor coalition that is championing the legislation. Much ink has been spilled already in taking deeper looks at both of these approaches; I personally suggest reading RIchard Day’s (pro-MMA) City That Works post about the larger reform efforts and the benefits of the Metropolitan Mobility Act in the context of less-comprehensive reform. However, MMA opponents have also made some very fair critiques of the legislation, most notably the idea that simply putting everyone under the same roof does not necessarily guarantee a more efficient transit operation for riders; any frequent user of the CTA undoubtedly has a few stories about missed bus-to-bus or train-to-train connections even within the same agency. There are also fears that with the MMA’s singular board split between the different “factions” in Chicagoland, someone will get (pardon the pun) railroaded by joint governance. Of course, these fears simply reinforce the existing siloed thinking that got us into this mess in the first place, and depending on who you talk to it’s either going to result in the suburbs running roughshod over the city, or the city running roughshod over the suburbs. In addition to concerns about Naperville calling the shots on the ‘L’, or the Fifth Floor deciding what transit in Will County should look like, there are also concerns from the folks who do the hard work of operating the buses and trains themselves: while union contracts could undoubtedly be resolved eventually, adding uncertainty and requiring new negotiations with any new agency is a level of instability the unions would understandably prefer to avoid.

On the opposite side of the argument, of course, is history: faced with a “doomsday” budget scenario in 2008, Illinois empowered the RTA with additional oversight tasks and duties as part of additional revenues to stabilize transit operations. Today, there’s understandably a healthy skepticism that, faced with a “doomsday” budget scenario in 2026, empowering the RTA with additional oversight tasks and duties as part of additional revenues to stabilize transit operations would not necessarily be a long-term solution. While the RTA’s “Transforming Transit” vision document, for instance, calls on the legislature to empower the RTA to create things like a unified fare product, this overlooks the inconvenient fact that the RTA was empowered by the legislature to create a unified fare product years ago, and has missed the statutorily-mandated deadline by a decade and counting.

While the MMA and the labor bills continue to work their way through Springfield, there is a potential third option that has not yet been fully explored in the legislation, a middle ground that could finally have found its moment: an RTA-like agency tasked not merely with “oversight” but explicitly tasked with managing a unified network and contracting out operations to publicly-owned operating units, which could then remain officially standalone agencies with their own boards of directors and local control of day-to-day operations and service delivery. This is something along the lines of the German verkehrsverbund model, of which Steven Vance has previously written a terrific primer on the subject. Since it can be an intimidating idea (and, of course, an intimidating German word to try to pronounce), let’s walk through what something like that could look like in Chicagoland in a much more user-friendly vernacular.

Introducing: Cartesian

For the purposes of this hypothetical, we will create a “new” agency named CARTESIAN: the Chicagoland Association of Regional Transportation Enterprises, Strategy, Innovation, and Accessible Networks. While it is quite a lengthy acronym, and for legibility purposes we’ll use “Cartesian” in mixed-case in this post, it is meant to be as widely-encompassing as possible, tasked with all aspects of creating a single, unified, regional transit network. From an artistic standpoint, the name also deliberately invokes the Cartesian coordinate plane, an infinite two-dimensional grid stretching to the horizon, which, let’s be honest, is more or less what Chicagoland’s transportation network looks like from the air.

Whether Cartesian ends up becoming a totally new agency that would replace the RTA, or a public RTA rebrand, or simply a shorthand way to refer to the new tasks delegated to the RTA, is ultimately a political question best left up to the politicians. However, Cartesian would officially become the provider of transit for all of Chicagoland: capital planning, service planning, procurement, communications, fare structures, and more would all become part of Cartesian’s core mission, and the Cartesian board would represent a broad geographic cross-section of Chicagoland, just like the RTA board currently does. To ensure one geographic “faction” could not overrule another, the Cartesian board would be required to have unanimity among its factions, but not necessarily among its full board. In other words, assuming Cartesian’s board would be constituted the same way as the proposed MMA board — 3 gubernatorial appointees, 5 collar county appointees, 5 Cook County appointees, and 5 City of Chicago appointees — board actions would need 11 out of 18 votes, but would require a majority of each appointing unit (2/3rds of the Governor’s appointees and 3/5ths of each of the other three constituencies) to ensure that everyone’s on the same page.

Cartesian, as a “transit association”, would be the sole agency responsible for coordinating present and future transit services for the entire region, including presenting a unified network vision for Chicagoland transit to ensure our entire system functions as a single, cohesive, expansive transit network. With a unified vision, Cartesian can take the lead on applying for discretionary funds and working with agencies like CMAP and our Departments of Transportation to identify, coordinate, and execute capital investment opportunities that are most beneficial to the region as a whole, avoiding potentially expensive duplication — or worse, competition — between projects currently segregated by mode or by operator. Similar to existing efforts by all three service boards and the RTA, Cartesian would also be empowered to help municipalities and neighborhoods create station-area plans and support local efforts to build and enhance transit-oriented development opportunities; unlike the current paradigm, however, Cartesian would be a “one stop shop” for these initiatives, rather than leaving station-area stakeholders to try to figure out who they should be working with based on mode or operator.

The Enterprise System

There is one key role that Cartesian would not have, however: like the RTA today, Cartesian would not directly operate any transit service in Chicagoland. Instead, Cartesian would contract out all day-to-day operations to enterprises, which would be the new name for the service boards. The primary difference between an enterprise and a current authority or service board would be replacing annual budgets with fixed-duration contracts between Cartesian and each individual enterprise. Rather than simply giving the CTA, Metra, and Pace’s annual budgets a thumbs-up or a thumbs-down as they do today (although a “thumbs down” has never been publicly issued anyway), there would be an agreed-upon contract between the enterprises and Cartesian, which spell out key performance indicators (KPIs), required minimum service levels, and incentives for meeting these targets. Contracts would not necessarily be competitive — there’s only a single enterprise that could operate the ‘L’, for instance — but they would provide verifiable, quantifiable, actionable metrics and service standards. By shifting from budgets to contracts, these accountability measures can be consistently managed throughout the life of the contract, with the boards of each enterprise empowered to directly hold accountable their respective management staffs based on contractually-required KPIs and service standards. When contracts need to be renewed, they can then also be renegotiated between Cartesian and the individual enterprises based on changing conditions, along with sweeteners for good performance — and perhaps mandatory accountability for unsatisfactory performance. (Note that “accountability” can take many forms and does not necessarily mean a funding reduction.) These contracts can also provide more stability with discretionary funds while also providing for reviews of discretionary fund allotment at regular intervals to help ensure the various enterprises are all appropriately funded based on overall revenues even as operating conditions may change and evolve over time.

Enterprises would be tasked exclusively with day-to-day operations, which also includes things like security as well as preventative and routine maintenance. Since capital planning and programming would become the responsibility of Cartesian, the enterprises would also have no need for bonding authority and would be required to maintain balanced operating budgets. Enterprises also allow for pass-through funding to guarantee each enterprise a financial “floor” — for instance, the Chicago Transit Enterprise could be guaranteed a very high percentage of all sales tax revenues generated within the city proper, with supplemental funds determined by the contracts with Cartesian based on farebox revenues (since Cartesian would own and operate all fare media and equipment) or other revenue sources that will inevitably be needed to bridge the fiscal cliff. With the near-entire focus on simply running high-quality regular service, the boards of each enterprise could focus exclusively on service performance and rider experience issues, providing a direct avenue of accountability both internally within each enterprise and for the riding public; enterprise boards could also include members of organized labor to ensure that front-line employees also have representation in each operating unit.

This is an important distinction between the two sides of public accountability: while Cartesian would be responsible for (and held accountable for) service planning — for instance, regional network planning, procurement, capital project prioritization, and so on — the enterprises would be responsible for service quality, like balanced headways, cleanliness, and reliability. This could ensure additional protection against something like a purely hypothetical scenario where executive staff allows service quality to severely deteriorate but an executive director politically could not be forced out because they have, say, a supposed knack for winning federal discretionary funding awards. While that scenario — again, totally hypothetical and in no way based on recent events — is entirely possible under our current governance paradigm and under less-ambitious RTA reforms, under the Cartesian system those particular skill sets would be entirely separated and responsibilities more explicitly delineated, ultimately improving accountability for service planning and for service quality.

The enterprise system also allows the larger Cartesian model to remain forward-compatible with future operators or entire modes. Maybe someday the South Shore Line joins, or Illinois Tollway becomes part of the fold, or even Divvy or a scooter operator wants to expand their footprint beyond the city proper. Rather than determine where to try to cram any of those entities into the existing enterprises, or make individual municipalities have to enter into new agreements on an individual basis that creates service gaps, Cartesian can simply create a new contract and/or adapt existing contracts at the next scheduled negotiation point.

In the context of this blog series though, service planning is where the rubber really starts to hit the road under the Cartesian model.

Cartesian Service Planning

At its most elemental and speaking operator-agnostically, Chicagoland has four primary modes of transit:

- Commuter/regional trains (Metra)

- The ‘L’ (CTA)

- Fixed-route buses (CTA and Pace)

- Microtransit (ADA paratransit, on-demand/dial-a-ride, vanpool, e-scooters, bike share, etc.)

Cartesian’s mandate would treat each of them accordingly, creating a single regional network plan and service schedules focused purely on what individual routes (and at what frequencies) would be the most efficient and effective to best serve the traveling public, regardless of who happens to be operating them or where they happen to operate.

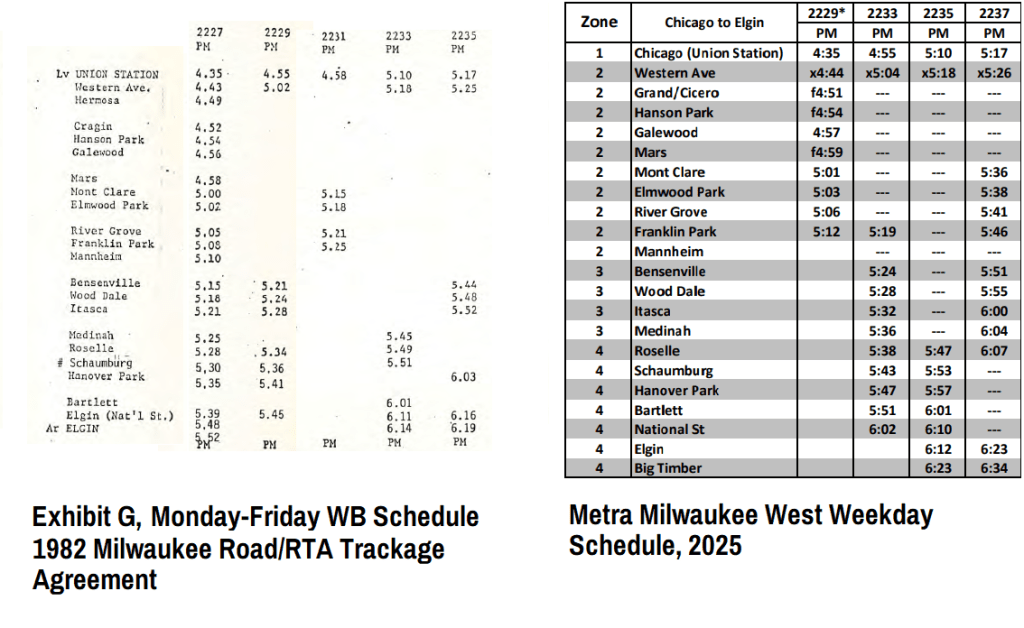

As we discussed in Part 2 of this series, the mode with the most restrictions in terms of operating frequencies and schedules is Metra, considering the agency’s reliance on and constraints with sharing tracks with freight railroads. First, Cartesian would work with Metra on an annual or semi-annual basis to establish regional rail schedules based on operating, funding, and labor constraints, and agree to a systemwide framework schedule.

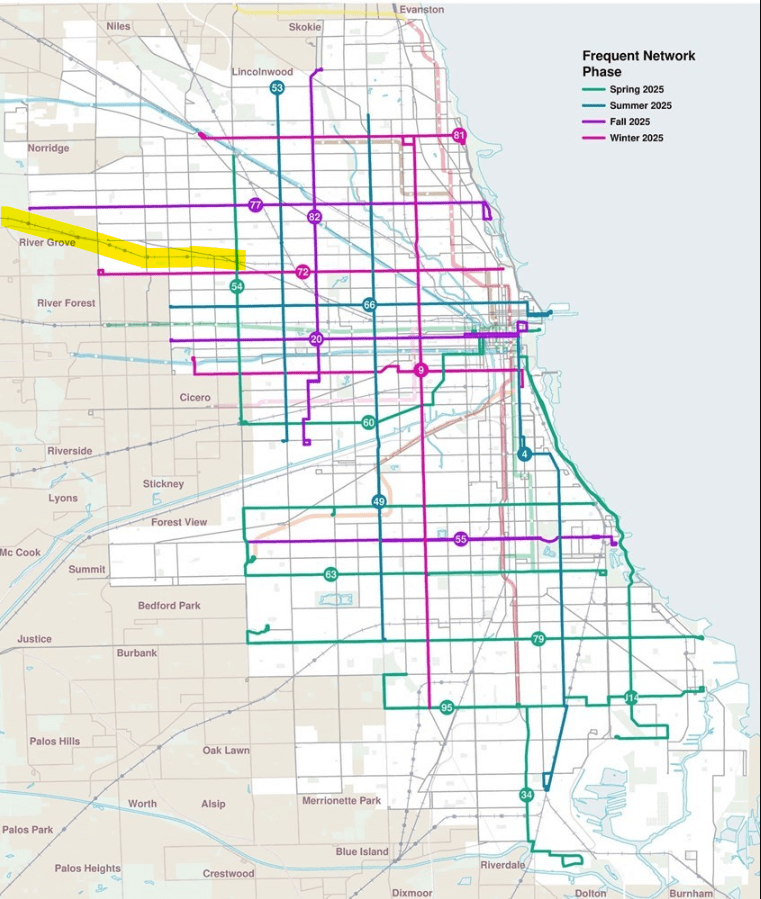

With the regional rail schedule in place, Cartesian would then move onto updating and creating service goals and schedules for the bus network, ensuring bus routes have intermodal connectivity throughout the entire region wherever possible and planning schedules accordingly.

90X Routes

Cartesian’s service planners would identify certain routes as 90x routes. The 90x designation (note: this is not necessarily a route number, but rather an internal categorization) denotes a high-frequency route, which would be defined as meeting the following criteria:

- The route operates seven days a week, with

- An average at least six trips per hour (average 10-minute headways) on weekdays, for

- At least 15 hours a day (5am-8pm) on weekdays, and

- No scheduled gaps of longer than 15 minutes during the same hours, as well as between 8am and 8pm on weekends.

Routes that would meet these criteria would operate at least 90 trips in each direction per weekday (6 trips per hour x 15 hours), hence the “90x” designation. Given the high frequencies, connections to regional rail trains would be assumed to be convenient enough to support show-up-and-go transfers; accordingly, the operating enterprises for these routes — which likely also would include most or all of the ‘L’ network — would handle scheduling entirely in-house, and the contracts for these routes would measure headway reliability rather than on-time performance. (This also provides an incentive for bus operators to find ways to operate more service, as routes that meet the 90x threshold would be scheduled and controlled internally rather than the enterprise being forced to operate schedules determined by Cartesian’s schedulers and service planners.) Likewise, 90x routes would have no restrictions on operating more frequently than the minimums established above, if the enterprise chooses to do so; this is intended to ensure city residents that Cartesian couldn’t “take over” busy city routes, considering a vast majority, if not all, of the 90x routes would likely be concentrated in Chicago proper. For routes that do not meet the 90x threshold — and, if needed, on 90x routes during early mornings and late evenings — scheduling would be centrally planned by Cartesian to ensure more convenient timed transfers to regional rail trains based on those schedules, as well as timed transfers (wherever possible) between non-90x bus routes.

As part of the regular contract negotiations, bus enterprises (Chicago Transit Enterprise and Pace) would bid on all bus routes, likely at the garage level. While it’s unlikely that the CTE would ever seriously compete with Pace for a collar-county route, and vice versa for routes in the urban core, this process would help ensure more efficient operations in the city/suburban “fringe” (like the Grand Corridor), as well as add a measure of cost control by allowing the two bus agencies to “compete” with each other in some areas without necessarily opening the market to private contractors who could undercut labor agreements. In either case, however, a typical rider would not be aware of the difference: publicly the system would be presented as a single network, using a single fare structure, with coordinated schedules between different routes and different modes, creating a seamless riding experience regardless of which enterprise happens to be operating the bus.

Ultimately, the Cartesian system would solve the problem that the Metropolitan Mobility Act is not guaranteed to solve, and what modest RTA reform efforts by definition cannot solve: existing oversight and coordination of our transit governance network is inherently passive and reactionary. Service boards are of course encouraged to work together and while they all claim to, our current governance structure can do no more than politely ask them to do so: the agency that ostensibly serves to unify the region’s transit network is only able to approve or reject whatever the service boards send them, rather than proactively creating and maintaining a unified network. While it’s true that the public transit needs of, say, 79th Street through the South Side are totally different than dial-a-ride services in rural McHenry County, it also is not a binary of “city transit” vs. “suburban transit”, even if plenty of elected officials (and transit users) on both sides of the 606XX divide may believe otherwise. The Chicagoland region is diverse in every sense of the word (except perhaps topographically), which means our transit needs exist on a broad spectrum of frequencies, modes, and geographies. We can’t afford to continue only hoping for the best that our four different agencies are all actually moving in the same direction.

This series has focused on the Grand Corridor because the corridor is emblematic of all the reasons why our current transit governance and operating paradigm doesn’t work, but also because of the incredible potential the corridor has if we’re able to reorient how we govern, how we operate, and how we fundamentally think about our transportation network as a whole. This is not a hopeless situation; nothing is broken beyond repair, but rather it’s just frustrating and inefficient. The impulse to want to blow it all up and start over is understandable, as is the fear that doing so would take things too far and cause undue disruption and burden. Likewise, approaching the situation cautiously and easing our way into considerable reform efforts is also understandably appealing, but may result merely in reform in name only, with no serious changes and ending up in yet another doomsday governance scenario once again another decade or so down the line.

We cannot afford to go over the fiscal cliff; significant new revenues are sorely needed simply to keep the lights on at our transit agencies, to say nothing of the need for generational investments in transformative transit. However, there is no — nor should there be — appetite for major new investments without also modernizing our transit governance structure, expanding accountability and creating a unified regional approach to improve transit for all of Chicagoland.

For nearly 80 years, Chicago-area transit funding, operations, and governance have been defined in some variation of a looming structural failure and finding a way to prop up the failing system: whether that was creating the Chicago Transit Authority to bring the ‘L’ and bus companies under public control after World War II, or creating the Regional Transportation Authority in the early 1970s to subsidize the railroads struggling to operate commuter service as well as saving failing suburban bus operators, or spinning off Metra and Pace a little over 40 years ago to directly operate suburban transit services, or tweaking board structures and funding formulas in 2008 to keep buses and trains running, every iteration of reforms have been focused on keeping a faltering 20th-Century model sputtering along until the next “doomsday” inevitably comes back around. A quarter of the way into the 21st Century, we have the opportunity — and responsibility — to finally break that cycle by making the effort to start imagining the unified, cohesive, coordinated regional transit network we want, and then determining how we can reform and retool our agencies to get us there.

We are Chicagoland. We are a region that gets things done, whether that’s raising our city out of a swamp, or literally rising from the ashes to become one of the fastest-growing cities in human history, or reversing the flow of an entire river to protect our drinking water, or building a sprawling network of tunnels throughout the region to fight floods, and throughout all of that our transit and transportation networks have always quite literally been the circulation that pumps prosperity and vitality throughout our city, our region, our state, and the entire Midwest. We owe it to ourselves and future Chicagoans and Chicagolanders to do better than just keeping the lights on.

Make no little plans.

#BuildTheTunnel