As we hurtle ever closer to the fiscal cliff, there’s been a lot of talk and discussions in Chicagoland about not only the importance of a safe, reliable, efficient transit network, but also what those investments — or forthcoming lack thereof — could mean for the city and the region as a whole. Concurrently, cost projections for the CTA’s Red Line Extension (RLE) have continued to increase, last year spiking from $3.6 billion to $5.75 billion in a matter of weeks. An unchecked 60% spike in projected costs should attract a lot of attention as we continue to discuss the best ways to maintain, operate, and expand our transit network to serve the entire Chicagoland region, especially chronically-disinvested areas like Chicago’s Far South Side. Given the rich history of CTA-vs.-Metra relations, how the RTA oversees (or doesn’t oversee) the service boards below them, and political promises for decades, there is undoubtedly a lot to unpack in a project that could very well become emblematic of the challenges our agencies and our transit network as a whole face in the 21st Century.

But let’s talk about a different corridor.

In the first of three Diverging Approach posts, we’re going to take a deep dive into the Grand Avenue corridor between Cicero Avenue and Mannheim Road: an ideal intermodal corridor that has come to encapsulate the siloed thinking and missed opportunities of the six major players of our current transit network: the three service boards, the RTA, CMAP, and our highway agencies. This post will set the table of the existing conditions in the corridor, how they came to be, and how tantalizingly close our missed connections are in what should — and could — be a dynamic, working-class, transit-oriented corridor between the two largest economic centers in the Midwest. Later posts will take a look at how reforms currently being discussed and debated in Springfield could reshape the transit user experience in this area, and how this corridor can become a keystone of a unified vision for 21st-Century Chicagoland transit.

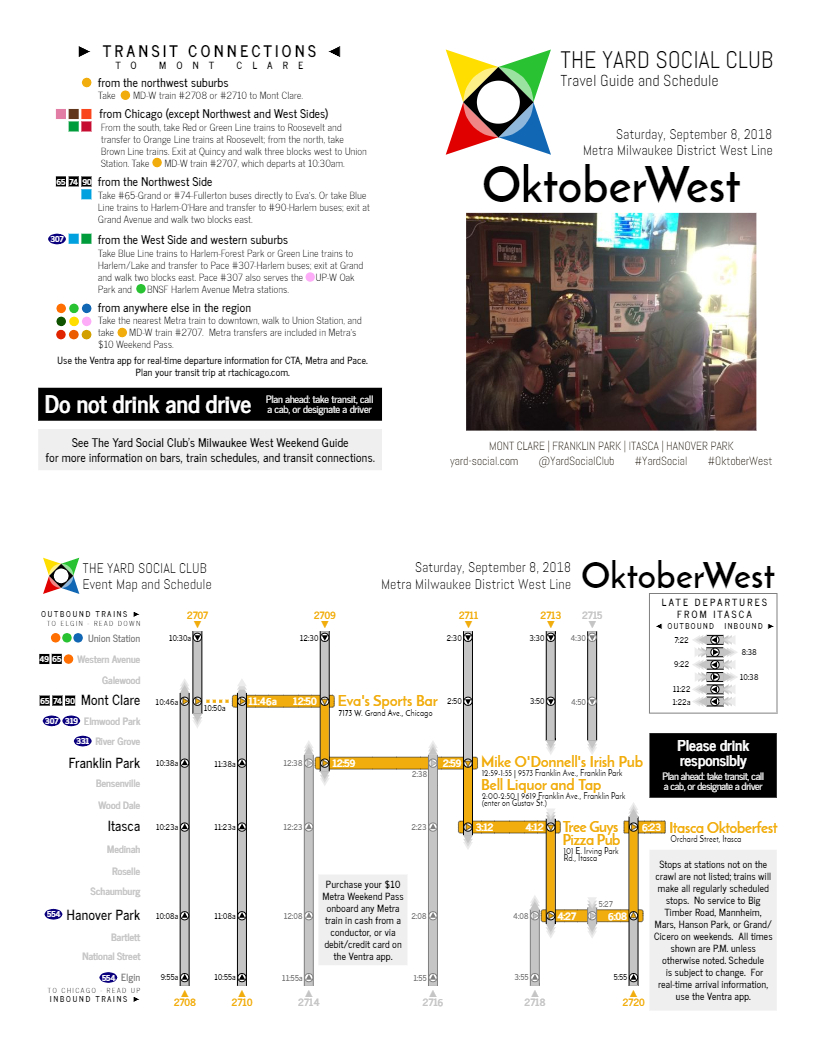

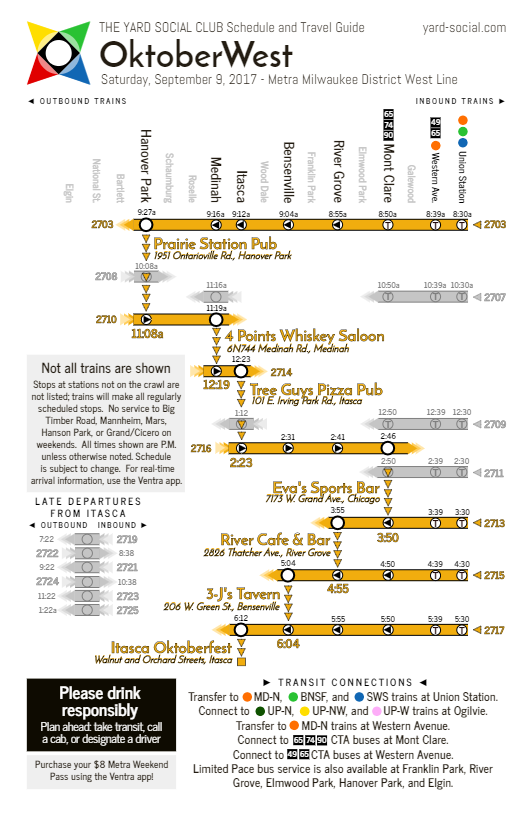

Out on one of the further edges of the city, where the West Side meets the Northwest Side and spills into suburban Cook County, lies Grand Avenue and Metra’s Milwaukee West line. Working-class communities straddling the city limits along nine stations that date back to the 1870s, this corridor more than perhaps any other exemplifies the challenges our region faces when we have three transit agencies with three different missions that all overlap, but not necessarily interact, with each other in the same corner of the map. However, the innate potential advantages of this corridor — which includes Metra’s existing North Central Service that connects this area to both downtown and O’Hare — can make a very strong argument for a more regional perspective in how we plan and operate our transit network.

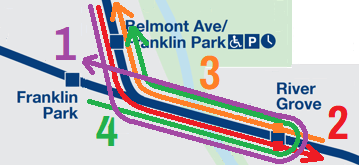

As of late, our three current service providers are all taking a closer look at this area in some capacity: Pace’s ReVision bus network redesign is ongoing; the CTA is beginning to roll out recommendations from its recent Bus Vision Project, including new 10-minute headways along the 54-Cicero and later this year, the 77-Belmont and 72-North corridors seen above; and Metra, perhaps perennially, is looking at adding more service between downtown and O’Hare via this rail corridor. However, these three efforts are mostly in parallel to each other, rather than a single coordinated effort to improve service. Each effort has its own goals: the CTA seeks to leverage its strong grid of bus routes to improve connectivity with other CTA routes; Pace is determining whether to concentrate its effort on increasing ridership, increasing service coverage, or some combination of the two; and news reports suggest Metra’s interest in improved O’Hare service thus far has been focused on express service similar to what was operated during last summer’s Democratic National Convention.

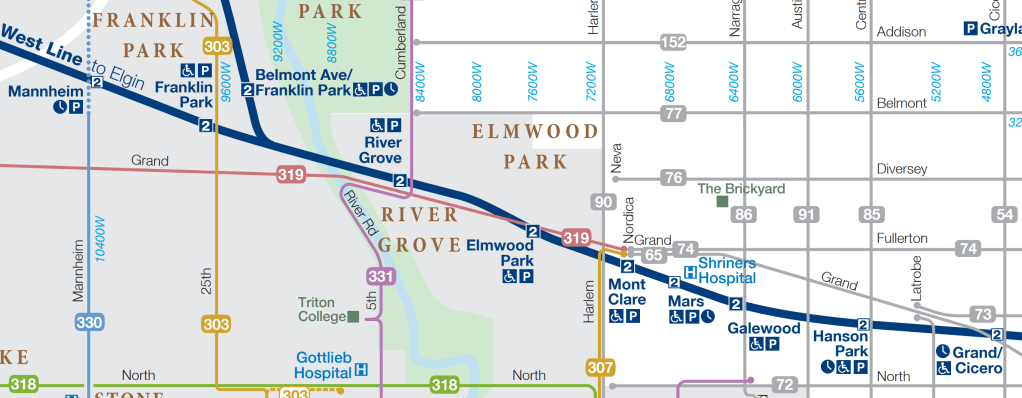

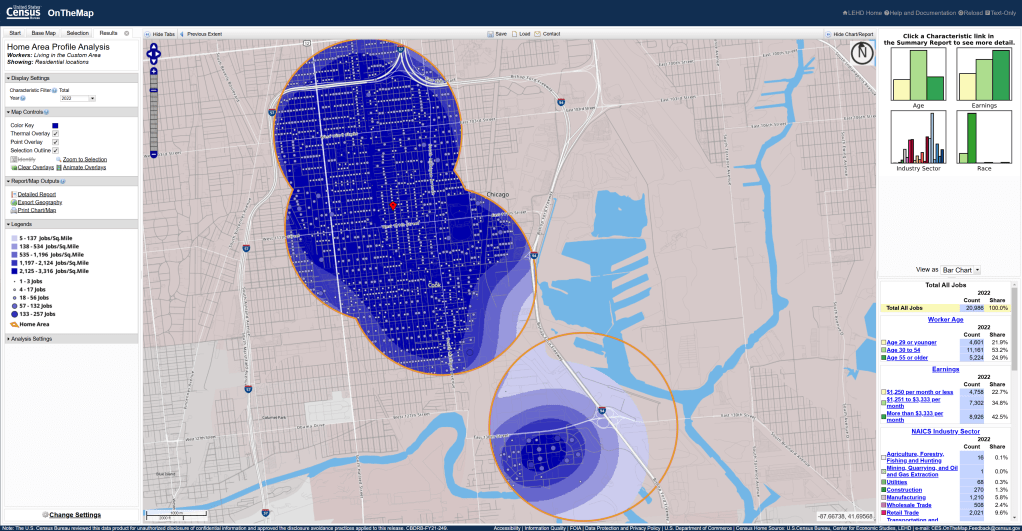

Demographics

Unlike many of Metra’s routes, the demographics immediately along this corridor are diverse and largely working-class. East of Harlem in the city proper, the tracks themselves define the community-area boundary between majority-Black Austin and majority-Hispanic Belmont Cragin and Montclare1. West of Harlem as the line leaves the city, the demographics shift to the majority-white — but quickly diversifying — suburbs of Elmwood Park and River Grove, which have both diversified from 85-87% white in 2000 to 57-62% white in 2020. After crossing the Des Plaines River, the rail line enters majority-minority Franklin Park, which covers the rest of the line to Mannheim Road. (West of Mannheim is three miles of rail yard.)

Median household income along the corridor is comparable to other working-class portions of Chicago, both for the parts of the corridor in the city proper and for the suburban stretches.

Unlike some of Metra’s other triple-track main lines through the city such as the Union Pacific Northwest, Union Pacific West, or BNSF Railway lines, there is no nearby CTA ‘L’ service and, as a result, this part of the city is something of a transit desert for city residents comparable to some parts of the Southwest and Far South Sides, despite the corridor’s proximity to O’Hare and airport-adjacent industries and businesses.

The corridor overall has a healthy density of residents and workers that could sustain more robust transit service. Collectively within a mile of each of the nine stations in the corridor, the Census Bureau reports over 76,000 workers as of 2022, just under half of whom made less than $40,000 that year. To put this in the context of the Red Line Extension, this area is slightly more than double the size of the respective 1-mile areas around the four new RLE stations but includes well over three times as many potential commuters.

Station Areas

The rail corridor within the city has a strong industrial history that, in some cases, continues through to today. However, as the industrial economy continues to evolve in Chicagoland, opportunities for higher-density transit-oriented development are emerging in this corridor — especially if fast, frequent, reliable transit service can be established. Some of these opportunities, and the challenges at many of these stations, are detailed below.

An important detail about this corridor is how the line itself was “modernized” following the creation of Metra’s North Central Service. For much of the 20th Century as part of the Milwaukee Road, this part of the line was somewhat unique in that it functioned as two side-by-side two-track railroads, with passenger trains using the north pair of tracks and freight trains using the southern tracks to provide relatively conflict-free operations between Bensenville Yard and Cragin Junction, just east of Cicero Avenue. Unfortunately, this resulted in station buildings being constructed on the “wrong” (outbound) platform due to space constraints, which was an inconvenience for mostly-city-bound riders. As the Milwaukee Road fell onto harder financial times in the final quarter of the century, the fourth (southernmost) track was largely removed, and eventually the railroad was sold to Metra. Regrettably, when Metra made a major investment to increase service on the North Central Service in 2006, the line was reconstructed as a “traditional” three-track shared corridor similar to the Union Pacific West or BNSF Railway lines, which does allow for station buildings to be on the inbound platform but now require mixed operations. As Canadian Pacific Kansas City, the new “host”2 of the line, plans to increase freight traffic on the line, freight/passenger conflicts will continue to increase.

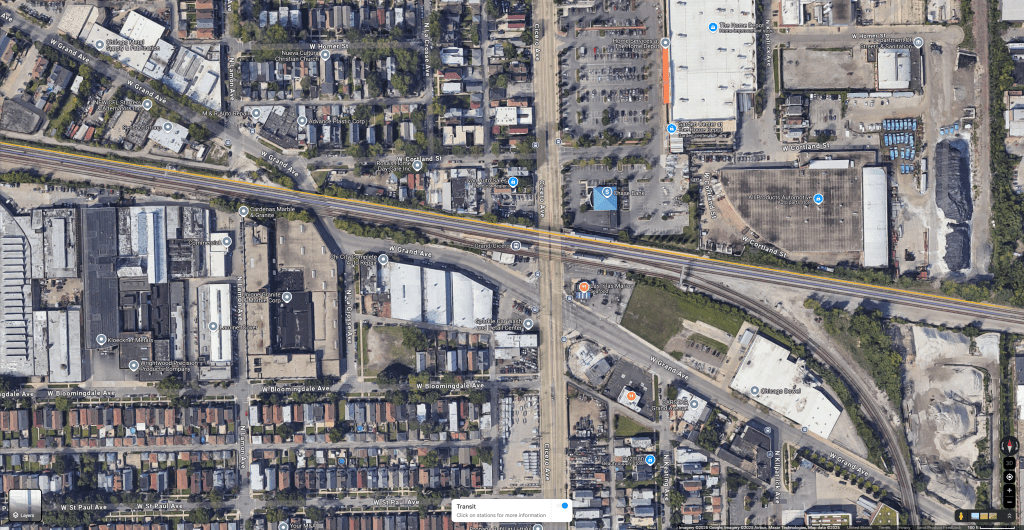

Grand/Cicero

Grand/Cicero opened in 2006 as part of the NCS “modernization” project as a consolidation of two former stations, Cragin to the west and Hermosa to the east. Grand/Cicero is ideally situated just north of the eponymous intersection, built into the grade separation embankment. Fully ADA-accessible, Grand/Cicero has elevators that can provide direct connections to the CTA’s 54-Cicero and 65-Grand buses, the former of which has been identified as one of the CTA’s inaugural Frequent Network routes. Despite these connections, Metra treats Grand/Cicero as a weekday-peak-only flag stop, where trains will only stop upon request, and only during the weekday peak, leaving the station unserved midday, nights, and on weekends. As of this publication, Grand/Cicero is only served by 10 inbound trains and 6 outbound trains each weekday, all of which are either before 8:32am or between 3:26 and 6:26pm.

The northeast quadrant of the site, directly adjacent to the station, is occupied by a 10.5-acre Home Depot and Chase Bank.

Hanson Park

Hanson Park is located approximately one mile west of Grand/Cicero. Historically the site of a Milwaukee Road rail yard, the line is at-grade but Central Avenue crosses overhead just east of the platforms. While the station itself is officially ADA-accessible, access to Central Avenue is provided by a staircase that is not accessible to passengers with mobility disabilities. While there are bus stops in both directions for 85-Central buses — the only direct connection between the Milwaukee West line and Jefferson Park, the largest transit center on the Northwest Side — the stairs to the bridge are only on one side, and transferring to or from a northbound bus requires jaywalking in the middle of the bridge.

Across the street from the Hanson Park train station is an overflow parking lot for the Chicago Police Department facility east of Central Avenue; the CPD facility also includes two Circuit Court of Cook County facilities for misdemeanor cases. South of the tracks, a large, low-density union hall sits west of Central; east of Central is one of the only active movie theaters on the Northwest Side. Like Grand/Cicero, Hanson Park is a weekday-peak-only flag stop, with 9 inbound trains and 6 outbound trains a day and no midday, evening, or weekend service.

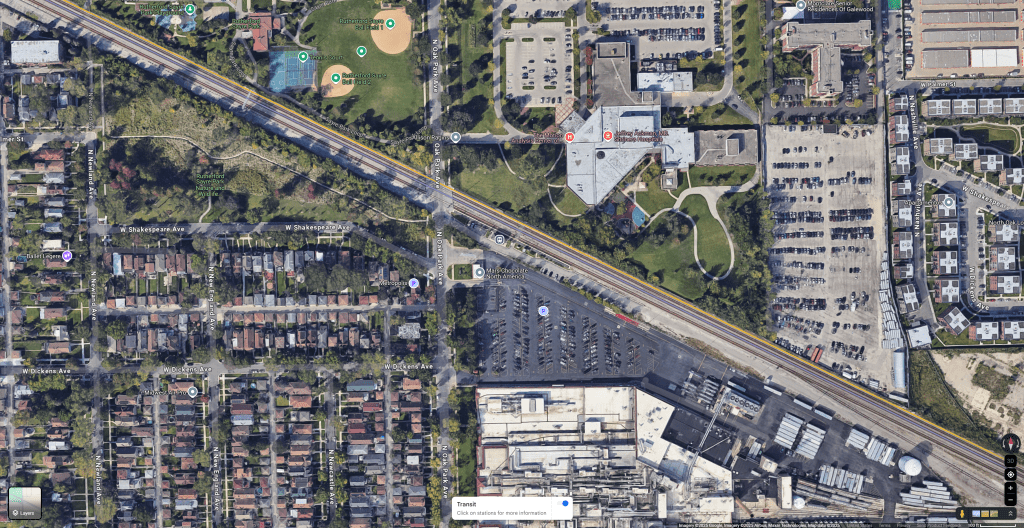

Galewood

One mile west of Hanson Park is Galewood, at Narragansett Avenue. In something of an inversion of Grand/Cicero and Hanson Park, this station is a full-time station for Metra with service seven days a week; however, this time it’s the CTA that operates limited connecting service as the 86-Narragansett/Ridgeland bus does not operate after 9pm during the week, and does not operate at all on weekends.

While active industrial uses are present on the northeast, southeast, and southwest quadrants, other than the Hostess bakery plant on the northeast corner the land uses are extremely low-intensity, with the southwest quadrant occupied by a self-storage facility and the southeast quadrant currently a surface parking lot used for CDL and truck driver training.

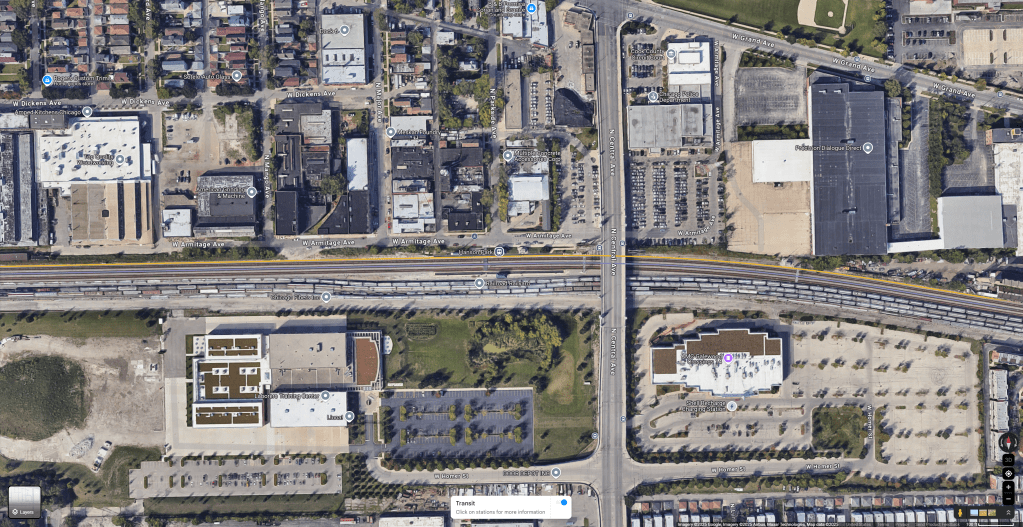

Mars

Mars, everyone’s favorite station name, is located just a half-mile west of Galewood at Oak Park Avenue. Oak Park Avenue is not a bus route, and like Grand/Cicero and Hanson Park, Mars is also a weekday-peak-only flag stop. While the station is flanked by Sayre Park to the west and the Shriners Children’s Hospital to the northeast, the station is named for the Mars candy factory just to the south of the station, which is currently studying how to redevelop the 20-acre site once the production line shuts down soon. More frequent — or at least full-time — rail service would certainly be a boon for any transit-oriented redevelopment possibilities for the candy factory.

Mont Clare

Less than half a mile away from Mars to the west lies the last station in the city proper, Mont Clare. Mont Clare is a full-time station, and absolutely infuriating from a network perspective. Harlem Avenue, one of the busiest north-south arterials in the area, is two blocks west; the CTA’s 90-Harlem bus does not directly serve the station. Grand Avenue, one of the busiest east-west arterials in the area, is one block north; the CTA’s 65-Grand and 74-Fullerton buses both do not directly serve the station either. Instead, these buses use the Grand/Nordica turnaround on the north side of Grand Avenue, which requires a short but unpleasant walk to connect from buses to trains. Pace’s 307 and 319 buses also use the Grand/Nordica turnaround, which means these routes also do not serve the Mont Clare station, even though the station is right there and Metra has more parking than they know what to do with and it would be just so easy to move the bus turnaround to the station itself and do literally anything better than what’s going on right now.

On weekends, even when trains are operating every two hours, the scheduled “meet” for these trains (where inbound and outbound trains pass each other) is scheduled just east of Mont Clare, with only a 4-minute separation between inbound trains (arriving on the :46) and outbound trains (arriving on the :50). With a bus terminal at the station, proactive scheduling means that this could be a perfect “pulse” location where buses come in on the :40 and leave on the :55 to provide plenty of time to make connections between buses and trains, while also providing operators with a solid 15-minute break and relief period. And yet…

If you want to know more about Mont Clare [missed] connections, just follow me on BlueSky and wait, I’m sure it’ll come up soon enough.

Despite the bus turnaround issue, the land use around the station is pretty good: mixed-density residential uses dominate the immediate areas that aren’t surface parking, with a neighborhood commercial corridor along Grand.

Elmwood Park

Once we cross Harlem Avenue we’re officially in the suburbs; the Elmwood Park station is about half a mile further west of Harlem, at 75th Avenue. Grand Avenue is served by Pace’s 319 bus, with a convenient signalized crossing at 76th Avenue. The 319 is relatively typical for Pace operations in Suburban Cook: buses operate half-hourly between about 5:30am and 7:30pm, with more limited Saturday service and no Sunday service.

The Elmwood Park station area is perhaps best known for the extremely shallow-angle grade crossing at Grand Avenue, the site of numerous fatal train-vs.-car crashes including a single 2005 crash that injured ten people and involved 18 vehicles. As a result, trains must reduce speed to cross the intersection, including express trains (such as Metra NCS trains) that do not stop at Elmwood Park. The Village of Elmwood Park and the Illinois Department of Transportation have secured funding to begin preliminary work for a grade separation in this location — a topic we’ll go into deeper in Part 2.

Land use and density near the station is somewhat typical of Chicago’s “inner tier” suburbs. Residential uses are mostly single-family, but on smaller city-sized lots with some three-flats and modest apartment buildings intermingled. While Grand Avenue comprises one of Elmwood Park’s busiest commercial districts, the town center of Conti Circle lies about a block northwest of the station. This town center includes most of the village’s municipal buildings as well as additional commercial and mixed-use buildings. Pace’s 307 bus formerly terminated in Conti Circle until the pandemic era, when the route’s terminus was shifted to the aforementioned Grand/Nordica turnaround near Mont Clare after several Conti Circle closures for street festivals.

River Grove

A little over a mile west of Elmwood Park is the River Grove station, a somewhat unusual station for several reasons. First and foremost, as is plainly seen in the aerial, the station is adjacent to two large cemeteries that occupy half of the station’s potential walkshed. However, the station is situated on Illinois Route 171, known variously as Cumberland Avenue, Thatcher Avenue, or 1st Avenue depending on where exactly one happens to be located along 8400 West on the city address grid. Pace Route 331, which runs from the Cumberland Blue Line to the Metra BNSF Line via a stop at the Maywood UP-W station, also serves the station via Thatcher. Half a mile north of the station, the terminus of the CTA Frequent Network 77-Belmont bus is tantalizingly close, but does not serve River Grove.

River Grove was not upgraded as part of the 2006 “modernization” of the three-track railroad; as such, the station building itself is on the outbound platform, with an island platform serving inbound (and, occasionally, some outbound) trains. River Grove is the designated transfer station between Metra’s Milwaukee West and North Central Service trains before the latter branches off about a mile west of the station and heads north towards O’Hare and Antioch. While the infrastructure is built to accommodate transfers, unfortunately the schedules are not: of the North Central Service’s seven weekday round-trips, one does not even stop at River Grove, and the other six have limited capabilities to actually connect to Milwaukee West trains, either as a local-express pair or as a more traditional transfer between lines. (North Central Service trains do not operate at all on weekends.)

Metra River Grove Weekday Arrivals, Departures, and Transfers

| NCS Train/Direction | NCS Arrival | MD-W Outbound | MD-W Inbound | Transfers? |

| 5:02am | ||||

| 5:38am | ||||

| 6:08am | ||||

| 100 (Inbound) | 6:32am | 6:50am | 6:46am | Yes (1, 2) |

| 102 (Inbound) 101 (Outbound) | 7:13am 7:31am | 7:19am | 7:19am | Yes (1, 2, 3, 4) |

| 7:54am | 7:50am | |||

| 110 (Inbound) | 8:15am | 8:19am | Yes (2) | |

| 8:54am | ||||

| 9:13am | ||||

| 112 (Inbound) | 9:15am | No | ||

| 9:54am | ||||

| 10:13am | ||||

| 114 (Inbound) | 10:25am | No | ||

| 10:54am | ||||

| 11:13am | ||||

| 11:54am | ||||

| 12:13pm | ||||

| 12:54pm | ||||

| 1:13pm | ||||

| 105 (Outbound) | 1:46pm | 1:54pm | No | |

| 2:13pm | ||||

| 2:54pm | ||||

| 3:13pm | ||||

| 107 (Outbound) | 3:46pm | 3:59pm | No | |

| 4:13pm | ||||

| 109 (Outbound) | 4:46pm | 4:39pm* | Yes (3) | |

| 116 (Inbound) | 4:52pm | 5:06pm* | 4:58pm | Yes (1, 2) |

| 5:25pm | ||||

| 115 (Outbound) | 5:56pm | 5:41pm | Yes (3) | |

| 117 (Outbound) | 6:21pm | 6:14pm | 6:13pm | Yes (3, 4) |

Despite half the walkshed occupied by cemeteries, the Village of River Grove has been proactively adding more transit-oriented development near the station, including a recently-opened 90-unit apartment complex.

Franklin Park

About a mile and a half west of River Grove and just past where NCS trains split off of the MD-W line at Tower B-12 is Franklin Park. The station is located just west of 25th Avenue, which carries Pace Route 303, a weekday3-only route linking the CTA Forest Park Blue Line and the CTA Rosemont Blue Line stations with an additional stop at the Melrose Park UP-W station. Similar to River Grove, the Franklin Park station also was not changed in the 2006 triple-track modernization and retains its (rarely-unlocked) station building on the outbound platform with an unsheltered island inbound platform. Its location between Tower B-12 and the east end of Bensenville Yard make this a chronic location for freight train interference and occasionally extensive delays as slow-moving freight trains stop and reverse. Metra also uses Franklin Park as the separation point between the “inner” (local) and “outer” (express) service patterns during weekday peak hours, which means that even when some of the useful NCS/MD-W connections are scheduled one stop east at River Grove, passengers riding to or from suburban MD-W stations may also have to make an additional transfer at Franklin Park to switch between express and local trains.

While the northeast quadrant of the station area was unfortunately recently redeveloped as a surface parking lot, the southwest quadrant has seen some relatively significant transit-oriented development within the last decade, including two six-story residential developments with ground-level retail. The southeast quadrant is currently occupied by the Park District of Franklin Park, another potential transit-oriented development opportunity in the future.

Mannheim

Finally, just under a mile west of the Franklin Park station lies Mannheim, one of the least-utilized stations in Metra’s network. The station, which is little more than two small platforms and a warming shelter on the outbound track, lies at the throat to Bensenville Yard. A historic whistle-stop community whose only remnants are a small dive bar and a plaque in the sidewalk, Mannheim is surrounded by light industrial uses and single-family homes. Similar to Hanson Park, Mannheim’s strongest opportunity would lie in more reliable connections to the bus route that goes over the station; Pace Route 330 uses Mannheim Road to connect the O’Hare Multimodal Facility (MMF) to 55th/Archer via downtown La Grange and the LaGrange Road BNSF. The route operates seven days a week with relatively quick runtimes — MMF to La Grange in under an hour — but has no connection to the Mannheim MD-W station due to the viaduct over the tracks with no vertical circulation down to the station. More frustratingly, the exact same situation occurs a few miles south at the Union Pacific West Line, where the 330 similarly misses a connection to the Bellwood station due to a lack of pedestrian access.

Not that it matters much here: similar to Grand/Cicero, Hanson Park, and Mars, Mannheim only receives weekday-peak-only flag stops, with eight inbound trains a day making the stop on request and a paltry four trains in the outbound direction.

West of Mannheim, trains can really open up and often get to 70 miles an hour as the Milwaukee West runs around the airport out to Bensenville and DuPage County.

If a realtor also happened to be a transit advocate, they would almost definitely describe this corridor having “good bones”: decent existing infrastructure with a fair amount of existing service and current land uses that could be quite conducive to transit-oriented development, but no one has been able to put the pieces together quite the right way yet. As Chicagoland transit continues to approach the fiscal cliff and as conversations start up in earnest about not only how to save our transit network but how we move towards the future transit network we want, the Grand Corridor makes an ideal candidate to better understand the untapped potential in our network and our region.

In the next installments in this series, we’ll take a deeper look into understanding the various major stakeholders responsible for improving transit and transportation in the Grand Corridor, and how some of the governance reform efforts currently being discussed in Springfield could play a role.

Finally, we’ll wrap up the series with what we believe should happen in the Grand Corridor, and present a bold, achievable vision for the future that demonstrates what a unified network can do — and how to make that vision a reality.

#BuildTheTunnel

- The Metra station is named “Mont Clare” — with a space — whereas the official community area is named “Montclare”, without a space. ↩︎

- Metra owns, operates, and maintains the Milwaukee West; however, CPKC dispatches the line and has inherited a sweetheart trackage rights agreement from Metra’s purchase of the Milwaukee Road that allows CPKC to have a functional veto of any Metra service changes outside of the weekday peak period (page 41). ↩︎

- Pace Route 303 also operates on Saturdays, but only between Forest Park and North Avenue without connecting to the Milwaukee West line or the Rosemont Blue Line. ↩︎

Editor’s Note: This post has been updated to correct the locations of the former Cragin and Hermosa MD-W stations, and to clarify the location of the freight turnoff at Cragin Junction.