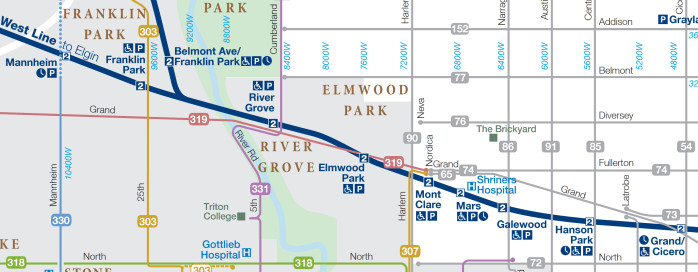

Welcome back to the ongoing Diverging Approach profile of the Grand Corridor, one of Chicagoland’s most underutilized transit assets. In Part 1 of this series we defined the current lay of the land of Metra’s Milwaukee West corridor between Grand/Cicero and Mannheim, a stretch of nine stations straddling the city of Chicago and the Cook County suburbs. Today the Grand Corridor is served by a disjointed mismatch of CTA and Pace bus routes, as well as legacy Metra schedules, that struggle to effectively serve local neighborhoods and communities despite existing, in-use transit infrastructure that connects to both the Loop and O’Hare.

The good news is that each of our major regional transportation players are all are working on improving the Grand Corridor, and in this post we’ll take a closer look at some of these initiatives, and how they fit into other regional improvement initiatives. But an early spoiler alert: different paths forward with different champions pushing different overall priorities has limited upside in the absence of a single, unified, cohesive regional network.

Chicago Transit AUthority

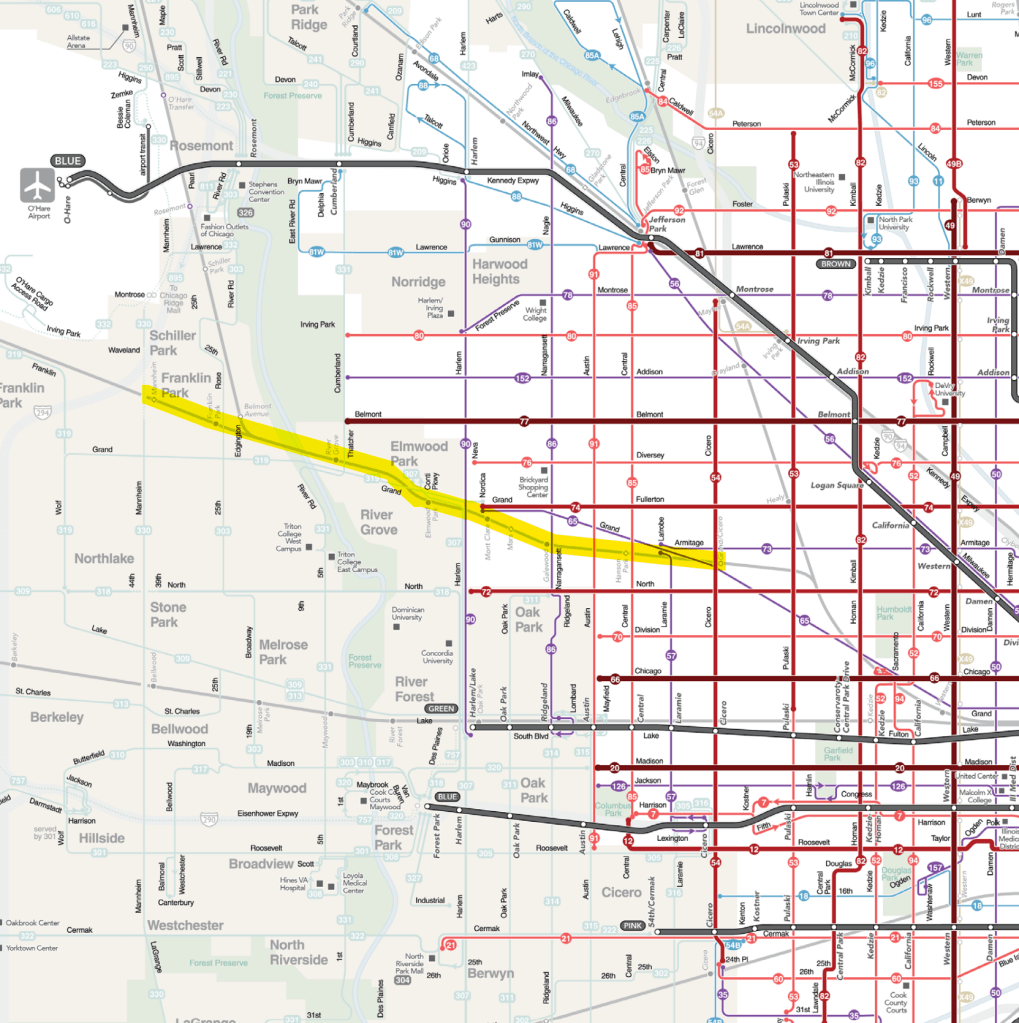

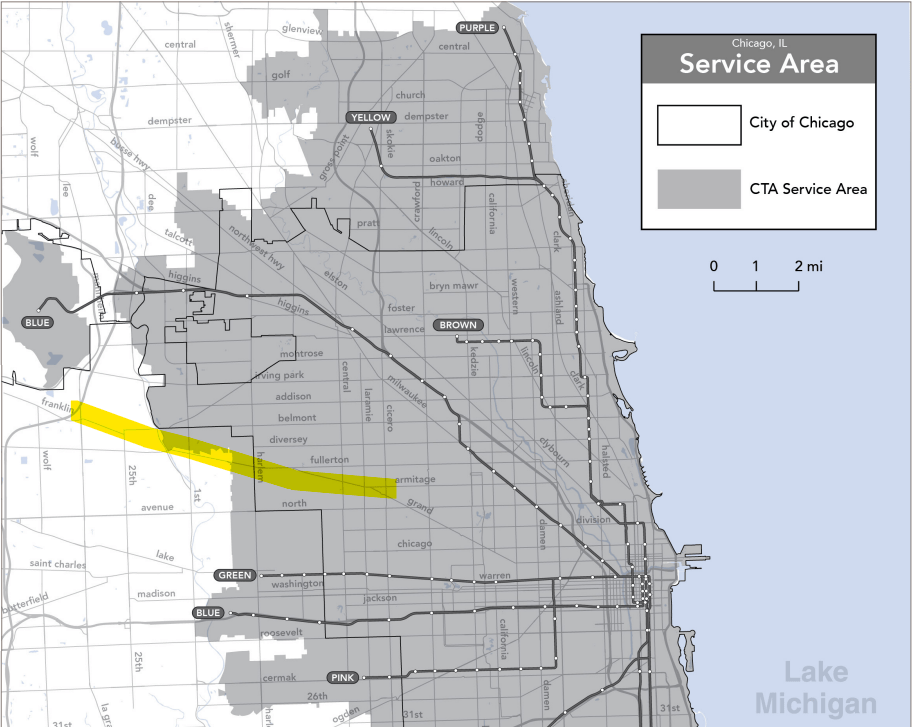

The Grand Corridor lies relatively far beyond the current reaches of the CTA’s ‘L’ network, a little over two miles north of the CTA Green Line and almost exactly equidistant between the two branches of the CTA Blue Line. Unlike certain other Metra corridors in the city, an extension of the ‘L’ system to provide rail service in this part of the city is not an option. As a result, the city portions of the corridor are served exclusively by CTA bus service.

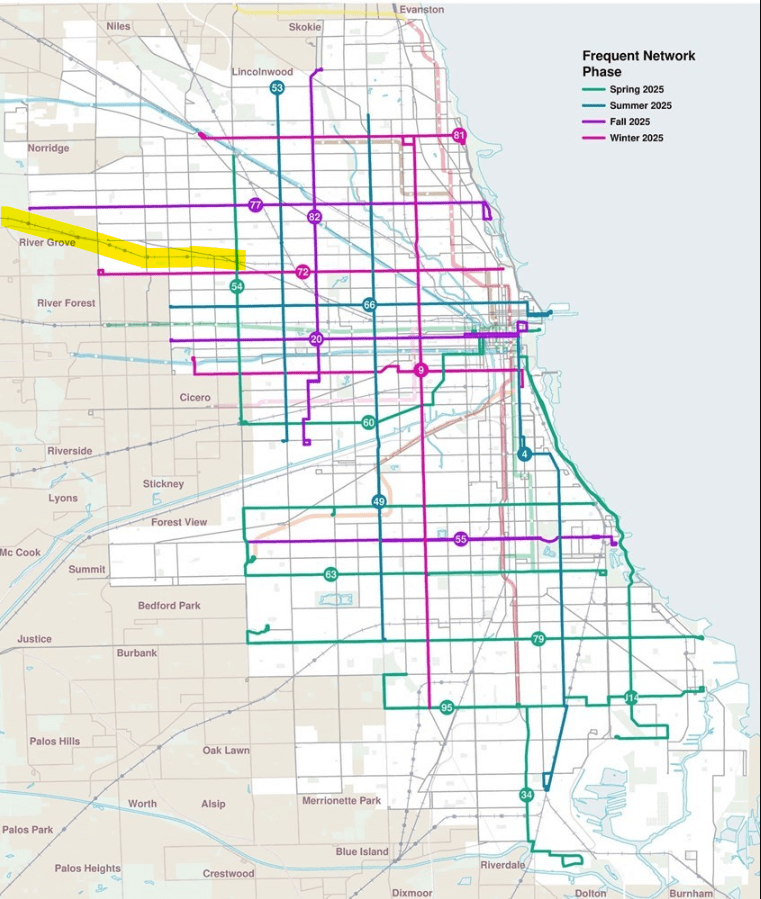

One of the preliminary results of the CTA’s Bus Vision Project is the establishment of the “Frequent Network”, a grid of bus routes throughout the city with headways of 10 minutes or less, seven days a week. Within the Grand Corridor, the 54-Cicero will be one of the first routes to see service improvements, namely a 30% increase in service on Sundays. Of course, since Grand/Cicero is a weekday-peak-only station for Metra, this bus improvement will have zero benefit in the context of this corridor. Next winter, the 72-North — a line that somewhat closely parallels the Grand Corridor, but does not interact with it — will also see service enhancements.

Perhaps the CTA bus service enhancement with the most untapped potential will be this fall’s enhancement of the 77-Belmont bus, which also ranked among the top ridership routes in 2024. The 77-Belmont terminates a mere half-mile north of the River Grove MD-W/NCS station at a turnaround near the intersection of Belmont and Cumberland Avenues. Despite somewhat recursively defining their service area as essentially “the areas we already serve“, there unfortunately seems to be zero incentive to extend the 77-Belmont to a two-line Metra station1 that is officially within the CTA’s defined service area. While the CTA has recently extended the 9-Ashland bus to a Metra connection at Ravenswood, since River Grove lies outside the city proper, it will be more challenging to get a city alderperson to champion this particular connection to Metra — and, of course, speaking more holistically, relatively minor transit extensions and connectivity should not need to be aldermanic passion projects.

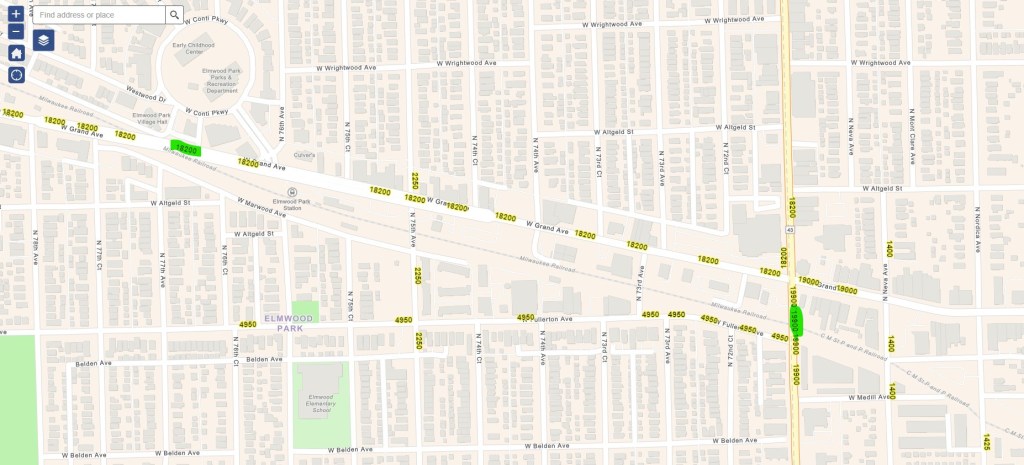

While we want to focus on the future, it’s also important to understand the past. Up until 2006, Harlem Avenue south of Grand was served exclusively by Pace: the 90-Harlem only operated between the [northern] Harlem Blue Line station and Grand Avenue, where the 90-Harlem turned east and terminated at the Grand/Nordica turnaround. Setting aside the Part 1 rant about how the bus turnaround is tantalizingly close to the Mont Clare Metra without actually serving it, this formed a little mini-hub for this part of the Northwest Side: CTA buses on Grand, Harlem, and Fullerton, as well as Pace’s Grand Avenue bus, all had a direct connection; and connections between the northern Harlem Avenue bus (90) and the central Harlem Avenue bus (307) could be relatively easily made by simply walking across the Grand/Harlem intersection2.

In 2006, CTA completed their West Side/West Suburban Corridor Study, a more holistic look at transit service on the West Side and the CTA-served western suburbs. While the headline improvement of the West Side/West Suburban Corridor Study was what would eventually become the Pink Line, the study also ended up recommended extending the 90-Harlem bus south to the Harlem/Lake Green Line to improve CTA rail connectivity to the Far Northwest Side. Unfortunately, there’s nothing in the study materials to suggest that Pace service was ever seriously considered, either as a way to improve said connectivity or in regards to impacts to Pace’s ridership. Since the structure of the RTA essentially leaves every service board up to their own devices (more on that in Part 3), the change to the 90-Harlem ultimately ended up shifting ridership from Pace’s 307 (and, further south, the 318) to the CTA’s 90-Harlem.

In the immediate aftermath of the extension, despite steadily increasing for several months prior, Pace ridership plateaued as CTA ridership grew, strongly suggesting that the 90-Harlem was effectively “cannibalizing” Pace’s ridership in the corridor. Prior to the extension, Pace had more riders than the CTA (although that trend was already weakening); following the extension, that dynamic swung in the other direction for the next seven years.

Over the years though, and as overall ridership stagnated, a different trend emerged likely due to the two different focus areas of the two different service boards. As the CTA was forced to rebalance service towards more “core” services in higher-ridership areas of the city, ridership on the 90-Harlem waned; however, for Pace, the 307 and 318 were — and remain — some of their best-performing routes, resulting in modestly improved service and, resultingly, a larger share of overall Harlem Avenue ridership. It took until 2017 for Pace to recover 307/318 ridership to its June 2006 level, by which time for various reasons 90-Harlem ridership had settled back below its pre-extension levels anyway.

Given the proximity to the Mont Clare Metra station, and now that Pace 307 terminates at Grand/Nordica, now would be an ideal time to cut the 90-Harlem back to its previous terminus and create a proper intermodal hub on the Grand Corridor, but…

Pace

…our suburban bus operator is heading in the exact opposite direction. Pace is currently undergoing a systemwide bus “network restructuring project” called ReVision. As of this publication, Pace and its consultant (same consultant who did the CTA’s Bus Vision Study, but not as a unified effort) are looking at three high-level future scenarios for Pace: a modest 10% service enhancement; a bolder 50% service enhancement focused on maximizing ridership; and a similar 50% service enhancement but focused more on providing wider coverage throughout Pace’s service area rather than solely maximizing ridership. (Assuming a future where a 50% expansion is feasible, it’s likely the final plan will be something of a hybrid of the latter two scenarios.)

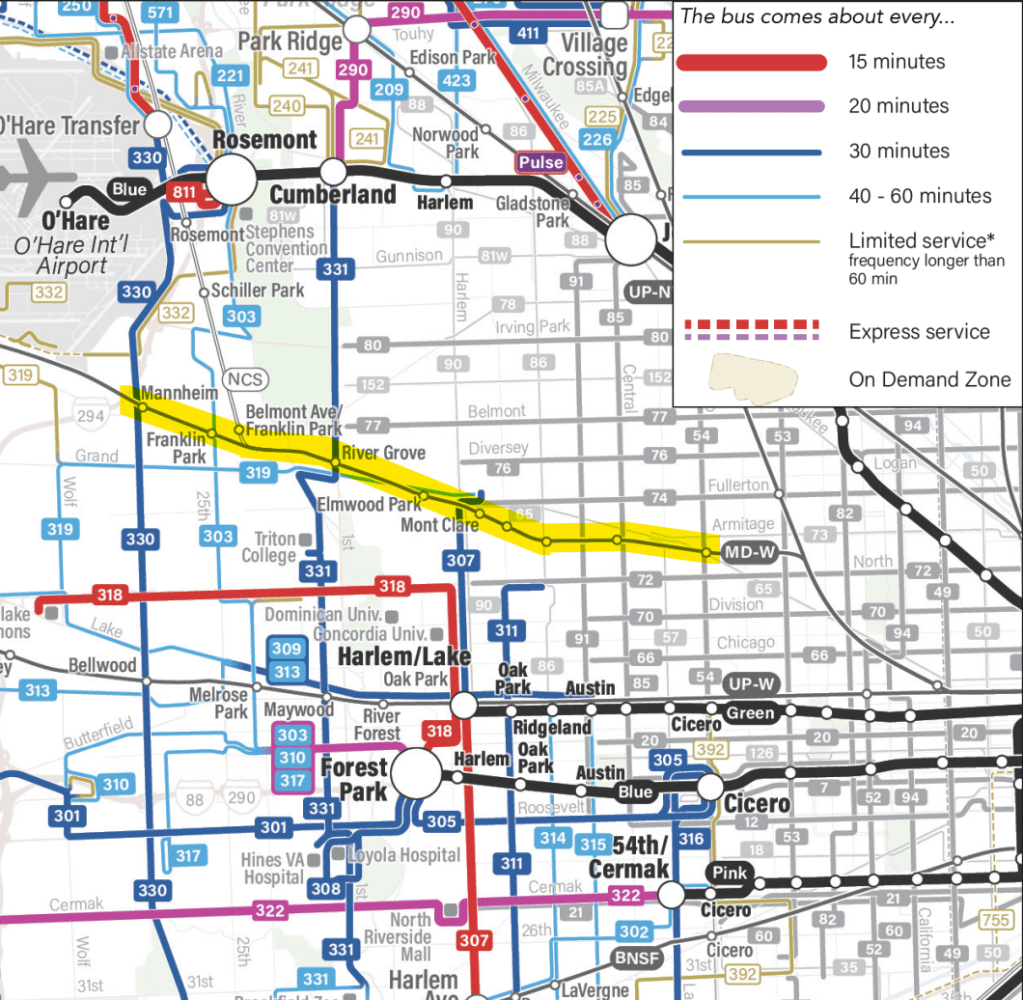

Unfortunately for the Grand Corridor, Pace seems to be heading down the path of the “east of Harlem is the CTA’s problem, not ours” siloed approach that has more or less defined the RTA era in one form or another. (Important caveat: the scenarios shown below, except the existing conditions, are intended to be illustrative of the network could look like, but are not an official proposal or plan; the concepts specifically regarding the Grand Corridor are cause for concern nonetheless.)

Existing Pace Network

Briefly recapping Part 1, four Pace bus routes currently serve the Grand Corridor, in addition to six CTA bus routes:

- CTA 54-Cicero serves the (weekday-peak-only) Grand/Cicero MD-W station

- CTA 65-Grand serves the (weekday-peak-only) Grand/Cicero MD-W station, is within a few blocks of the (weekday-peak-only) Hanson Park MD-W station, and serves the Grand/Nordica turnaround near the Mont Clare MD-W station

- CTA 74-Fullerton serves the Grand/Nordica turnaround near the Mont Clare MD-W station

- CTA 85-Central serves the (weekday-peak-only) Hanson Park MD-W station, assuming a rider is able-bodied and willing to jaywalk across an elevated viaduct

- CTA 86-Narragansett/Ridgeland (Monday-Friday only) serves the Galewood MD-W station

- CTA 90-Harlem is within a 7-minute walk of the Mont Clare MD-W station

- Pace 303 (Monday-Friday only) serves the Franklin Park MD-W station

- Pace 307 serves the Grand/Nordica turnaround near the Mont Clare MD-W station

- Pace 319 (Monday-Saturday only) serves the Elmwood Park MD-W station and the Grand/Nordica turnaround near the Mont Clare MD-W station

- Pace 331 serves the River Grove MD-W/NCS station

- Pace 330 does not serve the Mannheim MD-W station since the bus runs on a viaduct, not that it really matters since Mannheim is also a weekday-peak-only station

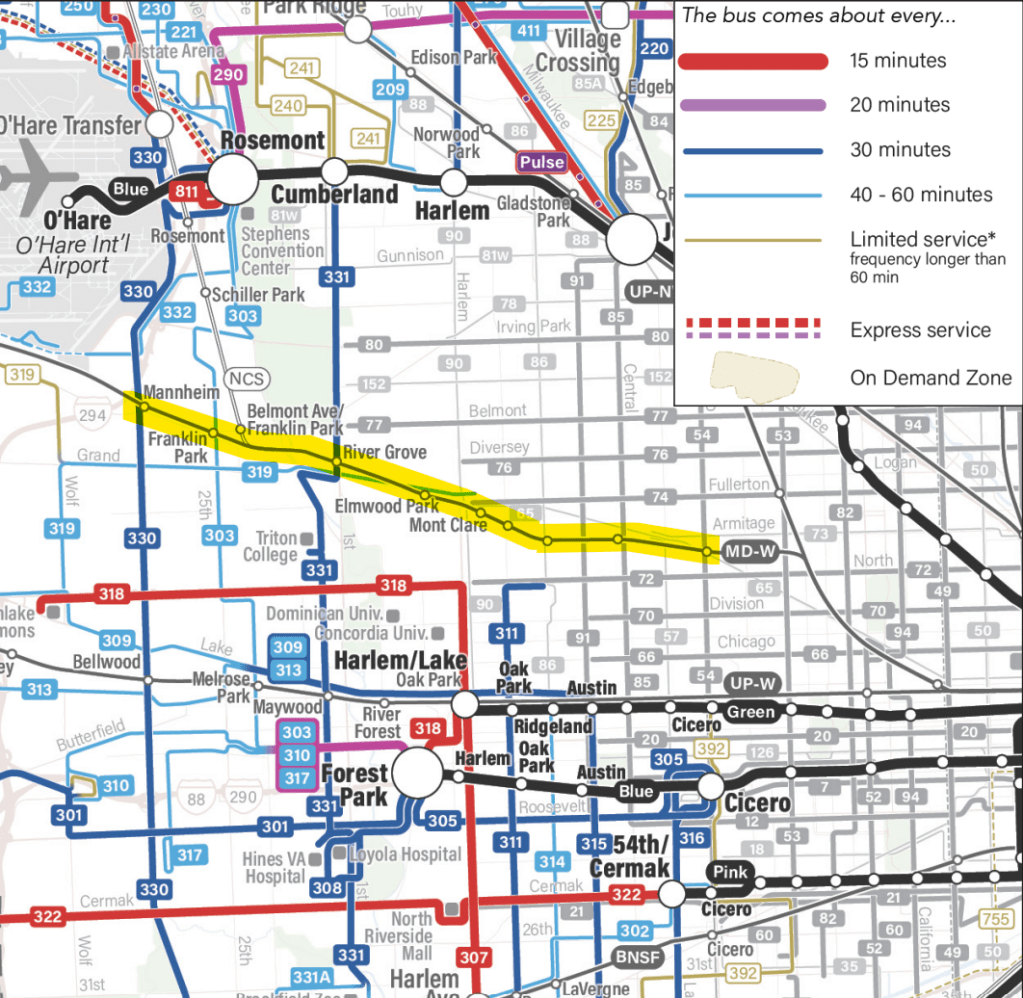

Pace PLus 10

Pace’s “Plus 10” scenario ultimately reduces service in the Grand Corridor, repurposing all 307 trips north of Harlem/Lake to elsewhere in Pace’s network since the 318 covers everything south of North Avenue and the CTA 90-Harlem can theoretically take care of the rest. This decision (and spoiler alert, this is common among all three scenarios), perhaps more than anything else, is one of the starkest shortcomings of these network redesigns: there is only a single bus route on the entire West Side/near west suburbs that connects all three western (“W#”?) Metra lines as well as the CTA Blue and Green Lines — and we’re considering dismantling it. That should be a five-alarm fire for anyone who cares more about creating an actual transit network in Chicagoland rather than maintaining our city-vs.-suburban agency fiefdoms.

Between Metra weekday-peak-only stations and bus lines without weekend service, Pace Plus 10 would include only one seven-day connection between the Grand Corridor and the Green Line (90-Harlem), zero direct connections to the [Forest Park] Blue Line, and only one connection to both the UP-W and BNSF lines (Pace 331).

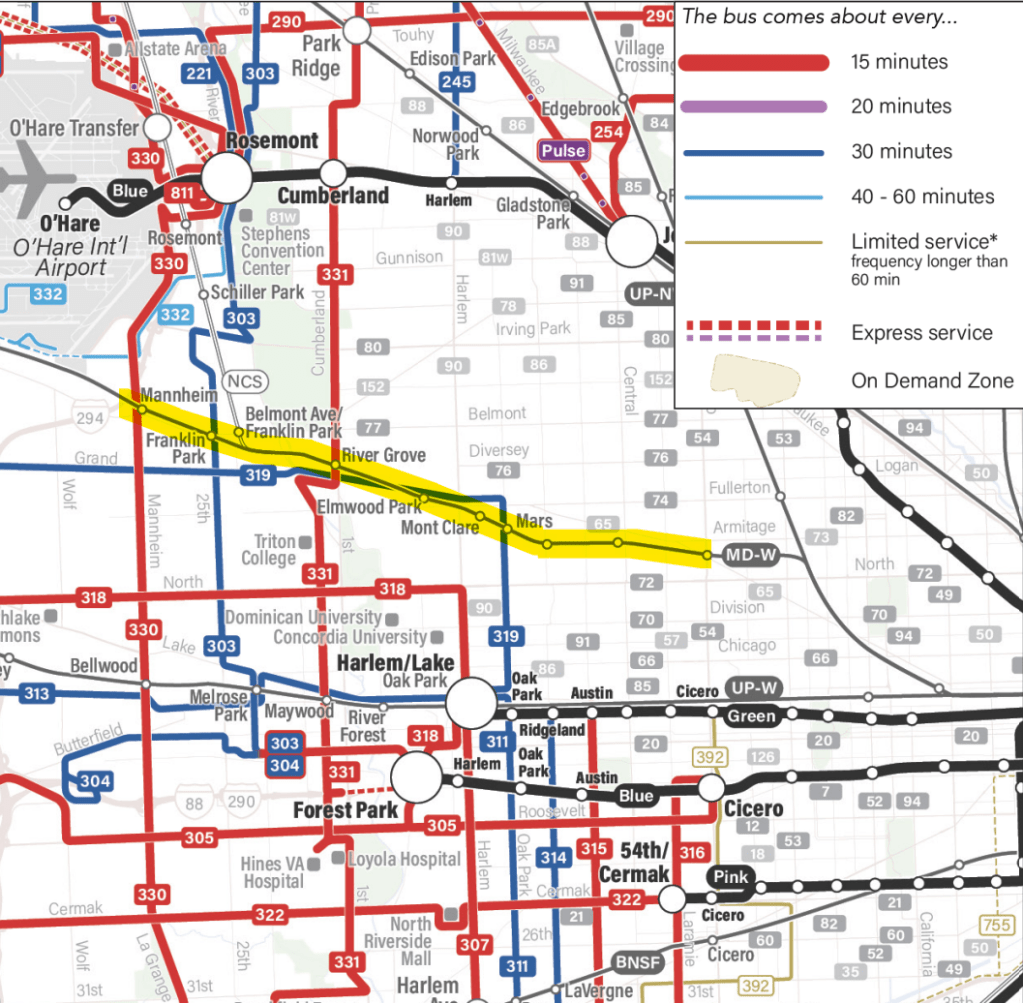

Pace Plus 50 – Ridership

Pace’s “Plus 50 – Ridership” concept also truncates the 307 at Harlem/Lake, despite reinforcing Harlem Avenue as a high-volume (and potential future Pulse route) south of North Avenue. More robust service on Pace 331 would benefit the Grand Corridor with more frequent connections at River Grove as well as a new express “spur” to the Forest Park Blue Line via Interstate 290, and a new Metra/Pace transfer point would be established by extending the 319 south down Oak Park Avenue (which does not currently have a bus route), then doubling back to Harlem/Lake. Of course, this connection would rely on transferring to Metra trains at Mars, which is a weekday-peak-only station. (319 would maintain a connection to the MD-W at Elmwood Park, but would require traveling an extra mile or so in mixed traffic on Grand Avenue relative to Mars.) Franklin Park would also benefit from a more-frequent 303 bus, as well as a stronger potential indirect airport connection (Franklin Park MD-W to 303 to Rosemont Blue to O’Hare). Added service on the 330 is once again a missed opportunity with no direct connection (and extremely low frequency of trains that stop) at the Mannheim MD-W station.

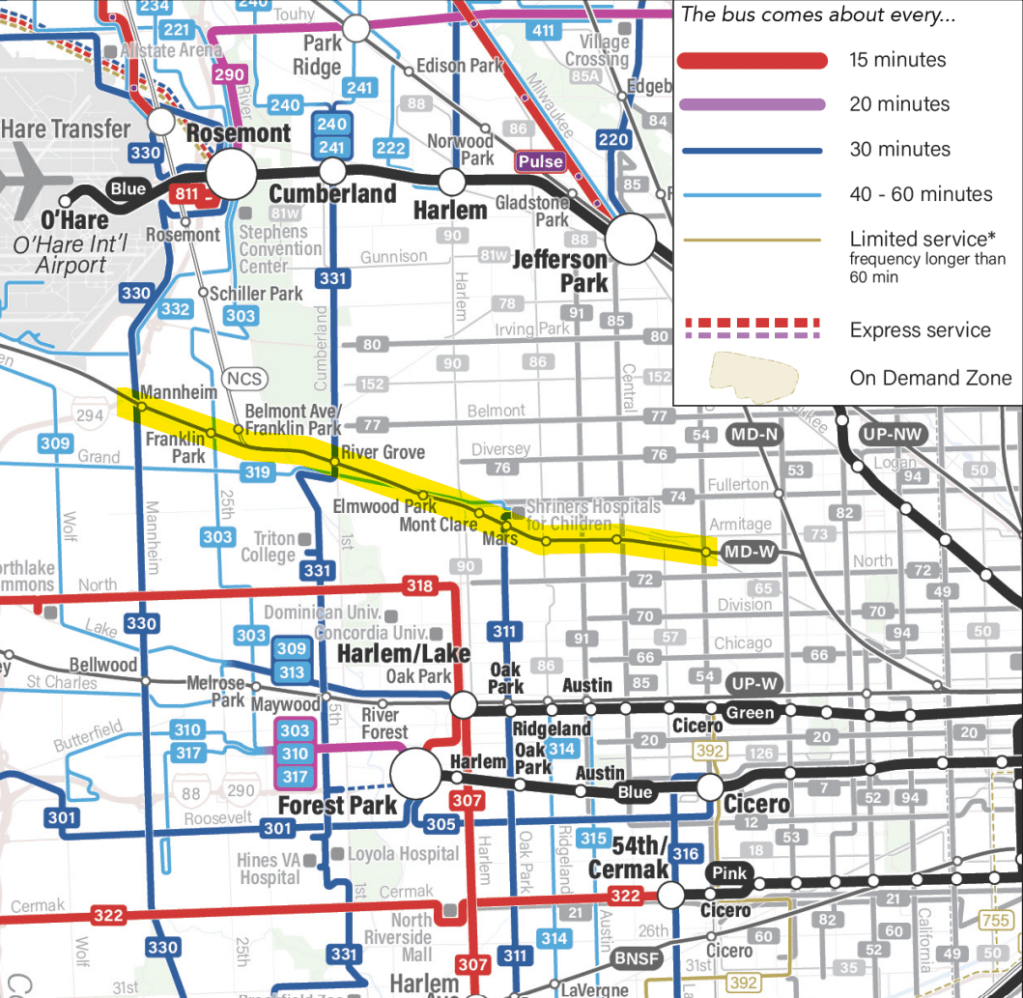

Pace Plus 50 – Coverage

The third scenario, which focuses on an enhancement of regional suburban bus coverage, would have far more modest impacts to the existing Pace network in this area. In this scenario the existing 311 (Oak Park Avenue) bus would be extended from North Avenue to Mars (which, again, no off-peak Metra service) and terminate at the Shriners Hospital.

Ultimately, despite all three scenarios being based on some level of increased overall Pace service, in this area the differences in the CTA and Pace bus networks would become more stark and siloed, rather than more integrated. With the very important caveat that Pace ReVision is still ongoing, and that the three scenarios are intended to be more high-level concepts, what they represent at this stage should still be considered an ongoing lack of regional network thinking in favor of a continuance of the precise “CTA’s for the city, Metra and Pace are for the burbs” line of thinking that we as a region so desperately need to break out of.

Metra

As an agency that had to quickly come to a reckoning in the COVID era (a transit agency that lives by the peak also dies by the peak), Metra has made some strides overall in at least understanding that the 2019-era paradigm is no longer a workable option post-pandemic. In February of 2023, Metra published their “My Metra Our Future” five-year strategic plan that, among other things, committed Metra to a transition from a “commuter rail” operational model to a “regional rail” operational model, which Metra defined by comparing the following attributes:

| Commuter Rail Characteristics | Regional Rail Characteristics |

| Operates at a higher frequency during peak periods and a significantly lower frequency off-peak | Whenever possible, includes service at regular intervals with consistent stopping patterns throughout the day |

| Schedules are more oriented to twice-a-day commuters | Service is not just oriented around bringing commuters to the urban center |

| Midday and weekend service is relatively infrequent | Provides an all-day transportation option for all trip types throughout the region |

| Trains operate at specific times rather than at regular intervals | Significant service during rush-hour to meet travel demand, but less frequent peak service than traditional commuter rail |

Metra tracks their progress towards the strategic plan with quarterly “report cards” that are published on their website. As of their most recent update (Q3 2024), Metra is making modest progress: systemwide, Metra’s “service restoration rate”, comparing the percentage of trains operated as a proportion of service in 2019, is above 100% on weekends and off-peak on weekdays; weekday peak service is only 84% of 2019 levels, indicating that Metra has indeed made it a priority to restore and improve off-peak service more quickly than their peak-oriented service. The scorecard also tracks the overall progress of Metra’s ongoing Systemwide Network Plan, which is intended to “identify how Metra can better service changing travel markets with regional rail service“. The Strategic Network Plan was considered 35% complete as of the Q3 2024 report card, and Metra says another round of public outreach regarding the Systemwide Network Plan is expected in “early 2025”.

On the Milwaukee West and North Central Service, however, service restoration and improvement efforts have stalled. For instance, the Grand Corridor is the only part of the Metra network that as of now has not yet regained their weekday late evening trains. Pre-pandemic, the last trains of the night from Chicago Union Station on the MD-W and NCS lines departed at 12:40am and 8:30pm, respectively; today, the final departures leave Chicago Union Station at 11:10pm and 6:00pm.

While Metra is able to occasionally add special supplemental service on a one-off basis (e.g., St. Patrick’s Day and DNC airport shuttles), Metra has said that, to add more frequent service between downtown and O’Hare, the host railroads (Canadian Pacific and CPKC — more on that in a bit) “won’t likely agree to a permanent change without infrastructure improvements,” according to an October 2024 Sun-Times article.

As we discussed in Part 1, the Grand Corridor is an interesting piece of infrastructure operationally and historically. The line was initially operated by the Milwaukee Road until that railroad ran into financial troubles in the early 1980s. As a result, in 1982 the Milwaukee Road entered a trackage agreement with the Regional Transportation Authority that allowed the RTA (and later Metra) to operate commuter trains between Elgin, Fox Lake, and Chicago Union Station, under the dispatching of the Milwaukee Road. When the Soo Line purchased the Milwaukee Road as the latter went into bankruptcy, what is now the “Milwaukee District” was not included in the purchase, but instead included a 99-year trackage agreement to allow Soo Line to use these tracks in a similar manner as Milwaukee Road established in the 1982 agreement. In 1987, RTA officially purchased the Milwaukee District from the Milwaukee Road’s successor, albeit with the 99-year trackage agreement to the Soo Line still in effect. Canadian Pacific took over the Soo Line, and more recently Canadian Pacific merged with Kansas City Southern to form CPKC, inheriting the trackage agreement at each transition.

All of this is to say that, if one dives really, really deep into Metra’s filing with the STB opposing the CPKC merger — page 124 — there’s a document that details how Metra is able to get vetoed by a private company as to how Metra operates Metra trains on Metra tracks. Specifically, with the exception of 5:30-8:30am and 4:00-6:30pm Monday-Friday, “[Metra] may not change the schedule without the [CPKC]’s prior written consent”.

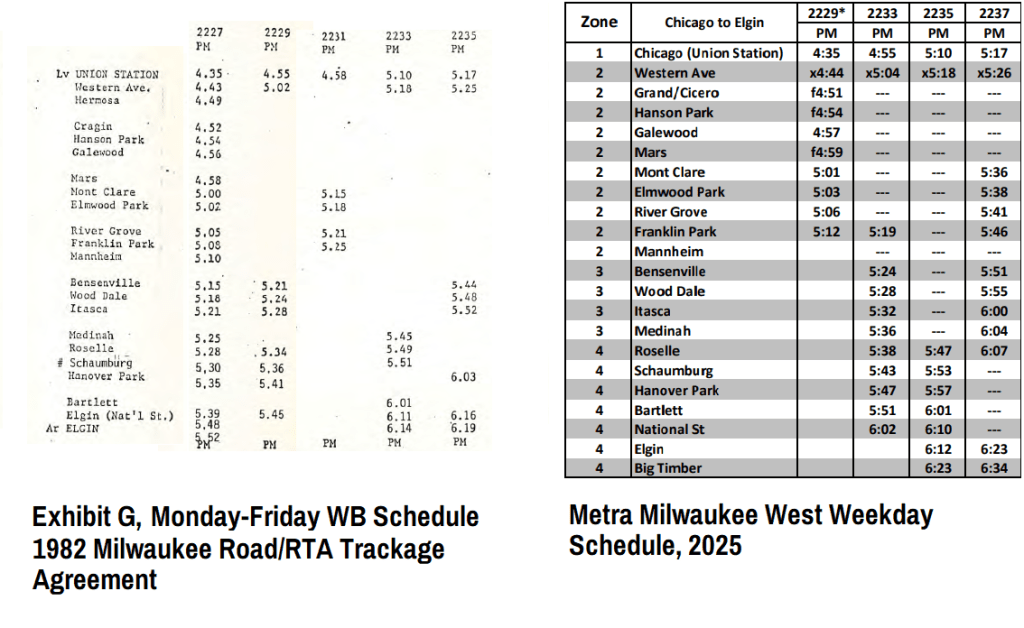

It’s also a bit uncomfortable how little the schedules have changed in the last 40+ years; other than train numbers and some station consolidations/expansions, the peak-of-the-peak westbound MD-W weekday schedule is nearly unchanged since 1982:

While a certain degree of these issues can more than likely chalked up to institutional inertia, Metra’s ongoing constraints to increasing service on the Grand Corridor — a line they already own — can best be described as parking-meter-deal-esque.

Illinois Department of Transportation

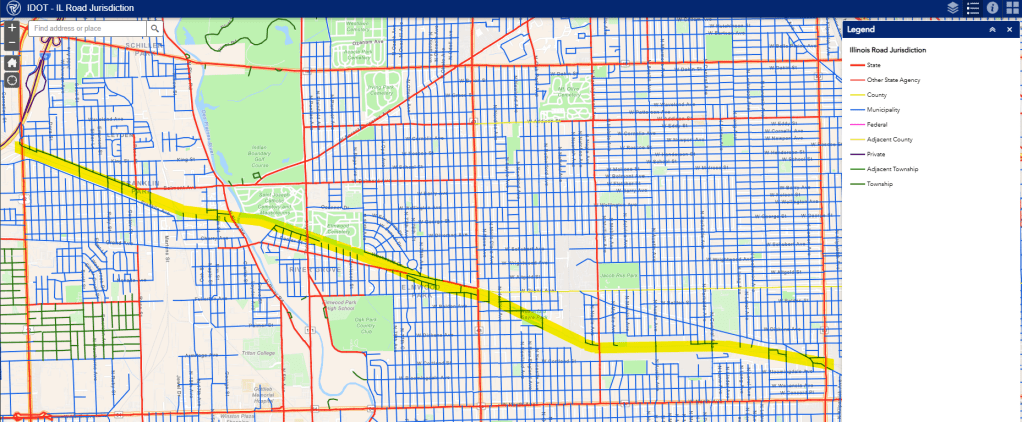

Like many parts of the city and near suburbs, IDOT has jurisdiction of many of the major streets along the Grand Corridor, above and beyond the three signed state highways (Thatcher Avenue/IL 171, Harlem Avenue/IL 43 and Cicero Avenue/IL 50). Other major crossings of the Grand Corridor under state control include Des Plaines River Road, Narragansett Avenue, and Grand Avenue itself.

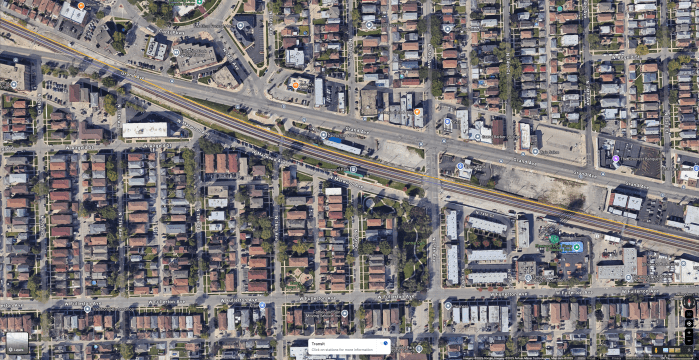

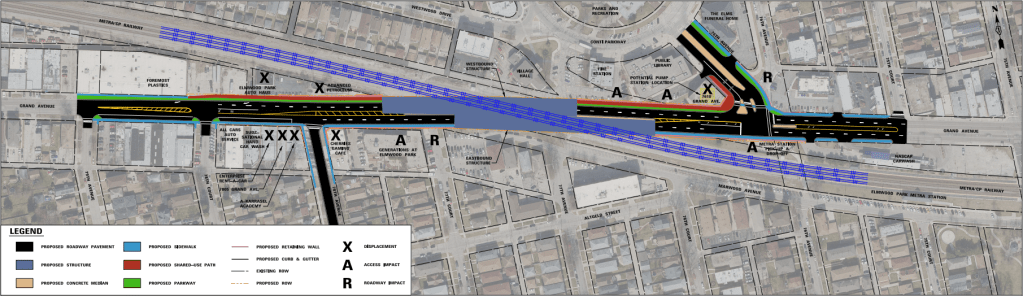

Following the infamous 2005 grade crossing crash that involved 18 vehicles and injured 10 people, IDOT began a grade separation feasibility study in 2007. Since then, under the branding of the “Grand Gateway”, IDOT and the Village of Elmwood Park have since been working on advancing plans for an underpass at this location, a $120 million project that recently secured $13 million for land acquisition.

While separating the Grand Avenue crossing is justly considered a transportation priority, the state and Elmwood Park are treating this (nine-figure) project as a spot improvement rather than a corridor enhancement. In this case, just 3,500 feet east of this crossing is the Harlem Avenue grade crossing, which also happens to carry more traffic as well as two bus routes (for now, at least).

If we were looking at the Grand Corridor as an actual corridor, this specific project could be the impetus for — or at least forward-compatible with — a larger-scale grade separation that includes Harlem Avenue to increase safety for all road users while speeding up our buses and trains. What’s particularly frustrating is how so many of the issues previously discussed could fall like dominoes if these efforts all lined up:

- The corridor elevation could ensure that a fourth main could be reinstalled to separate freight and passenger rail traffic, an important infrastructure improvement that could help Metra convince CPKC to allow more frequent passenger rail service.

- The corridor elevation would also allow (or require) relocating the Mont Clare Metra station to a location more suitable to also serve as a bus turnaround for CTA and Pace buses, creating a targeted intermodal hub to plan a proper, integrated neighborhood bus network around.

- As part of designing the new station, even in the absence of a fourth main, an island platform could be included to allow express NCS trains between O’Hare and downtown to stop here — which, again, would now be an intermodal transfer point serving both CTA and Pace buses — instead of River Grove.

- With this transit anchor near Harlem Avenue, the Harlem Avenue corridor — which intersects with and already has convenient stations for the CTA Green Line, CTA Blue Line, Metra Union Pacific West, and Metra BNSF Railway lines — could be properly prioritized by IDOT, CTA, and Pace to provide fast, frequent connections, opening up the entire West Side and near west suburbs to dramatically improved service to the O’Hare area.

- With just a little bit of creativity — considering it lies just three miles east of Harlem Avenue — we could connect this Harlem Avenue line to Midway instead of the current 307 terminus at SeatGeek Stadium, which would be downright transformational for massive swaths of the entire Chicagoland region.

But instead, with four different transportation agencies going in four different directions because each of them are focused on the specific niche they specialize in, here we are, with so much potential just slipping through the cracks. Since this corridor isn’t fully city and it isn’t fully suburban, it doesn’t fit neatly into one of those silos we’ve built for ourselves over the decades, so we simply don’t do it.

This series of posts is called “Six Degrees of Separation” because these four major players — combined with the two designated regional players that should be tying them all together, namely the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) and the Regional Transportation Authority (RTA) — have each been going their own way for too long, setting the table for the crisis we’re in now. While the current focus has been on the funding crisis for transit operations, and the governance reforms that will (hopefully) accompany a (hopefully) massive infusion of new funding into regional transit operations, what we really have is a crisis of vision, and a crisis of action: we need to be able to do big things again, and that starts with dreaming of the big — and even some of the more modest — things we want to make realities.

In Part 3, we’ll end on a high note by taking a look at what some of the current governance reform efforts could mean for the Grand Corridor, and present a potential new way forward for a transformative new vision for Chicagoland transit.

#BuildTheTunnel

- Extending the 77-Belmont due west to the Franklin Park MD-W station would also accomplish the goal of connecting the route to both Metra routes since the NCS line also has a station at Belmont Avenue, but the extension would be a bit longer, go outside the CTA’s service area as currently defined, and may result in service delays in case of freight train interference at the grade crossing. Repurposing some of the existing River Grove Metra parking as a bus turnaround would allow the 77-Belmont to avoid crossing any additional tracks at-grade. ↩︎

- Prior to 2024, the Pace 307 bus’s northern terminus was in Conti Circle in downtown Elmwood Park, via Grand Avenue west of Harlem Avenue. ↩︎