For nearly three years now, this blog has been beating the drum on “regional rail” and why we need to “build the tunnel”, but it may be helpful to take a step back and discuss at a more basic level what “regional rail” is and how it could work in a Chicago context.1

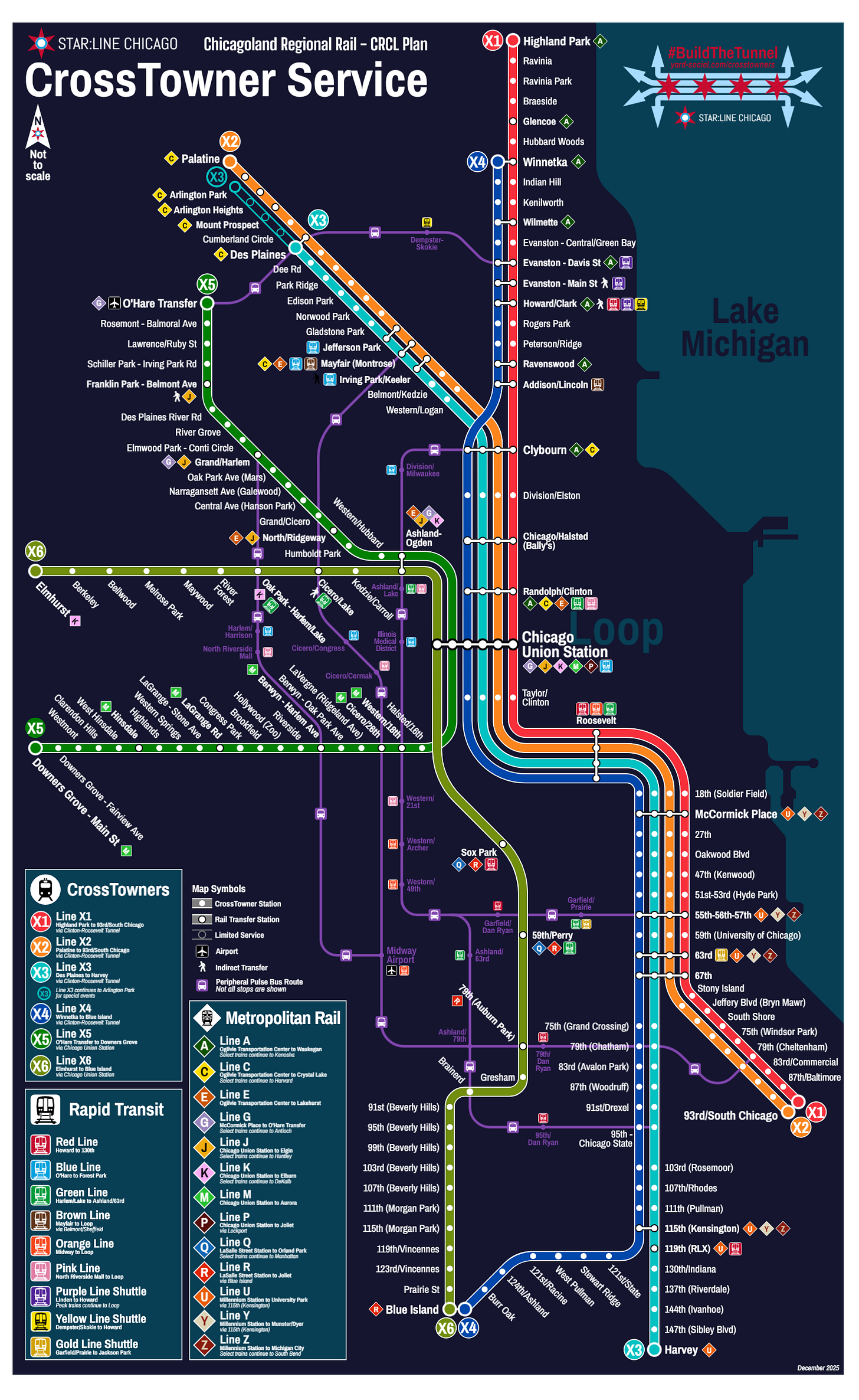

Regional rail is a “keystone” vision that would create a unified backbone for a modern regional transit network, with truly-regional benefits. While definitions of “regional rail” may differ, the CrossTowner proposal is fundamentally a third transit mode that is effectively overlaid on the existing Metra network, plus creating new strategic downtown connections.

In the interest of level-setting, at a conceptual level “thru-running” regional rail works by creating one or more trunk lines to connect existing Metra lines via downtown. As more branches converge into the trunk line, train services overlap and the individual lines contribute to higher frequencies through the trunk, so riders who are heading from one trunk station to another do not need to worry about which train is which since they all make the same stops. (For instance, on the existing Metra network, a rider who boards at the Western Avenue station near Hubbard Street does not care whether their inbound train is MD-N or MD-W or NCS since all the trains go to Union Station regardless.) In addition to providing additional connections to other parts of downtown for “traditional” commuters, rather than making all riders get off at separate terminals just outside of the Loop, new longer-distance direct trips are also created, expanding the reach of the network to a wider potential audience of transit users.

Fundamentally there are two different models of regional rail networks.

Philly-style: one tunnel wit commuter rail schedules

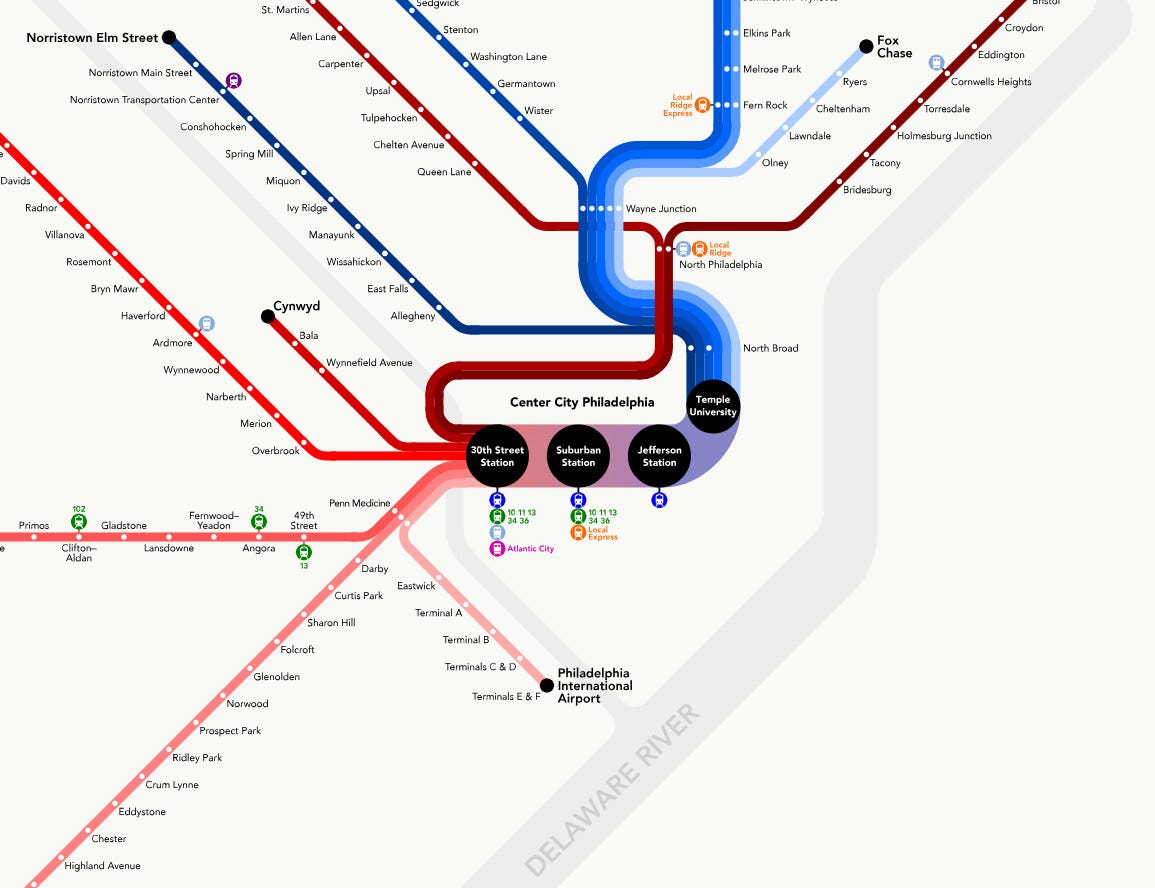

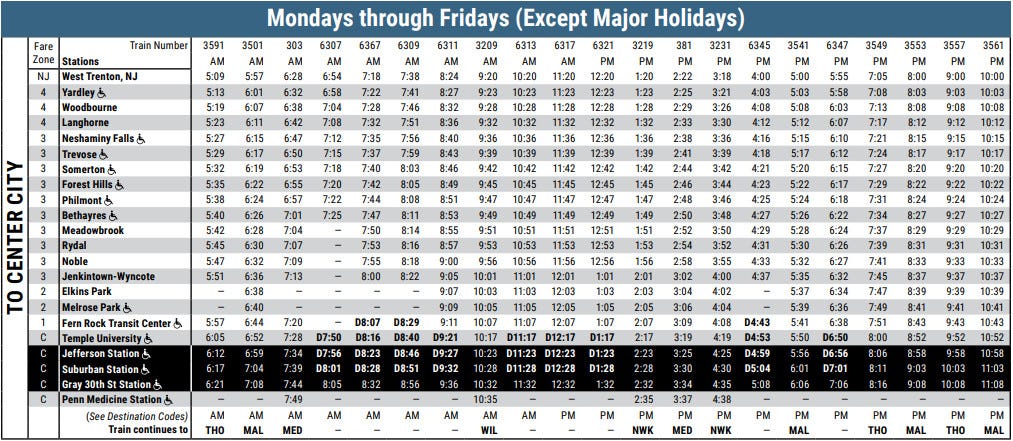

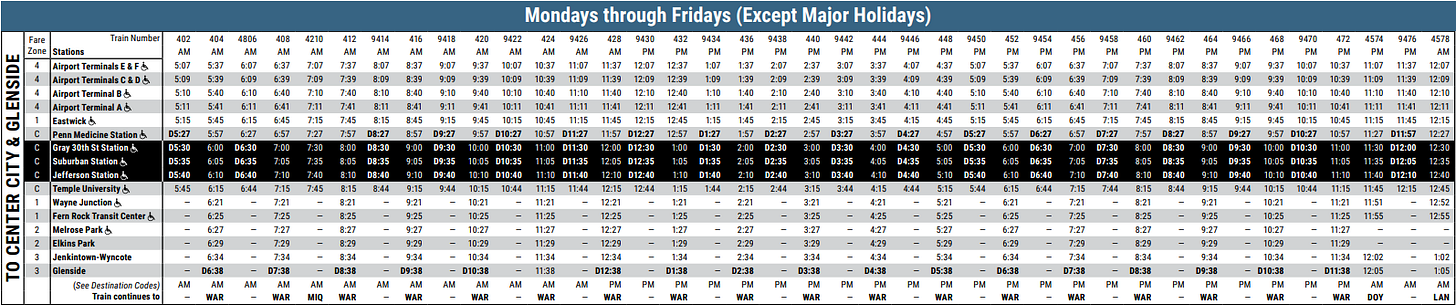

In Philadelphia, SEPTA operates regional rail through their Center City Commuter Connection tunnel, which opened in 1984. This connection created a unified network by connecting the Pennsylvania Railroad’s historic commuter lines that entered Center City from the west with the Reading Railroad’s commuter lines that entered Center City from the north.

While the Center City Commuter Connection allows for all commuters to access multiple stations in Center City, SEPTA still fundamentally operates the system as a commuter railroad: off-peak headways are still high (generally hourly), and the central “trunk” is relatively short. Furthermore, through-routes are not consistent throughout the day: riders traveling beyond Center City still need to regularly consult printed schedules to determine which trains end up where, with most intra-regional trips still requiring a coordinated transfer.

Prost: A toast to the Munich S-Bahn

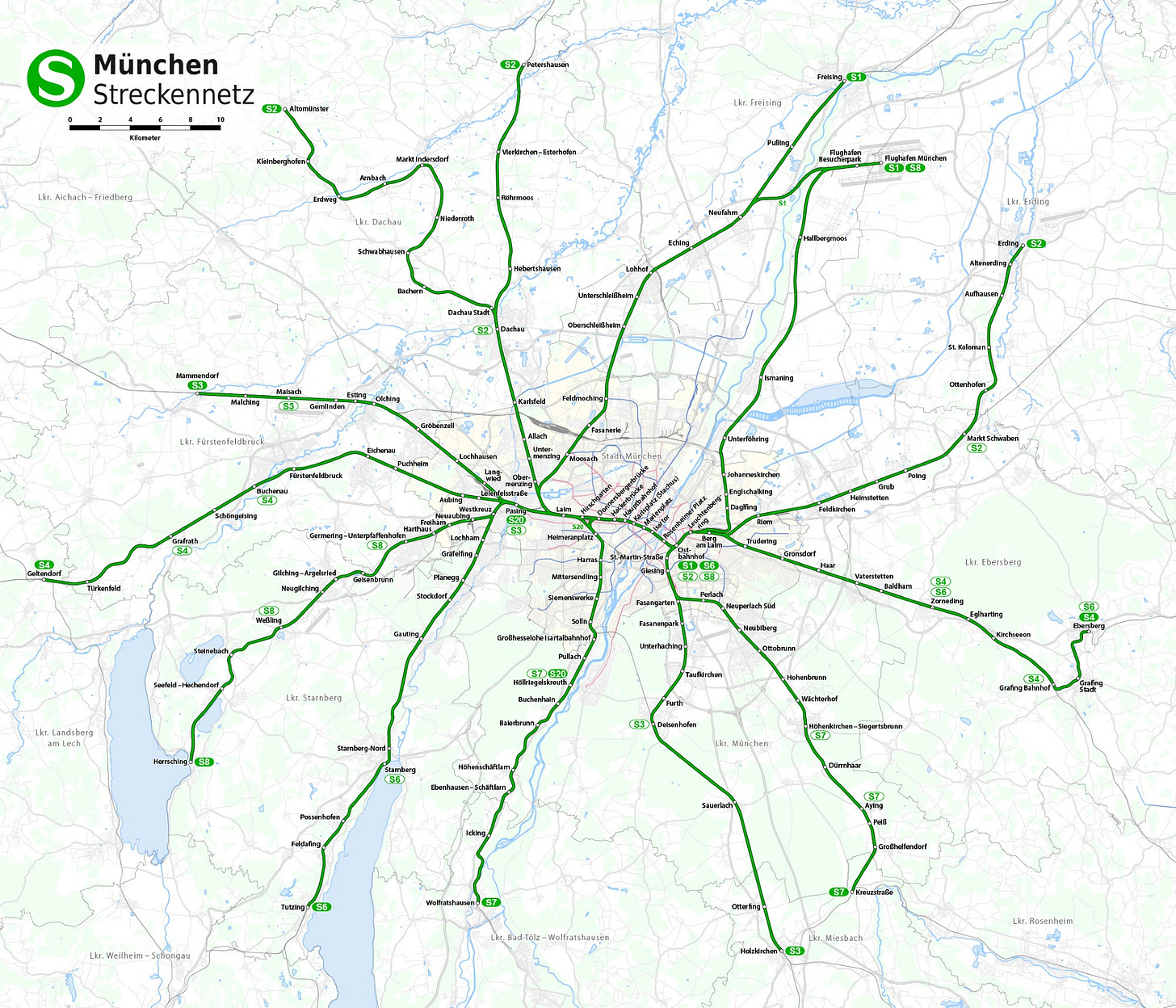

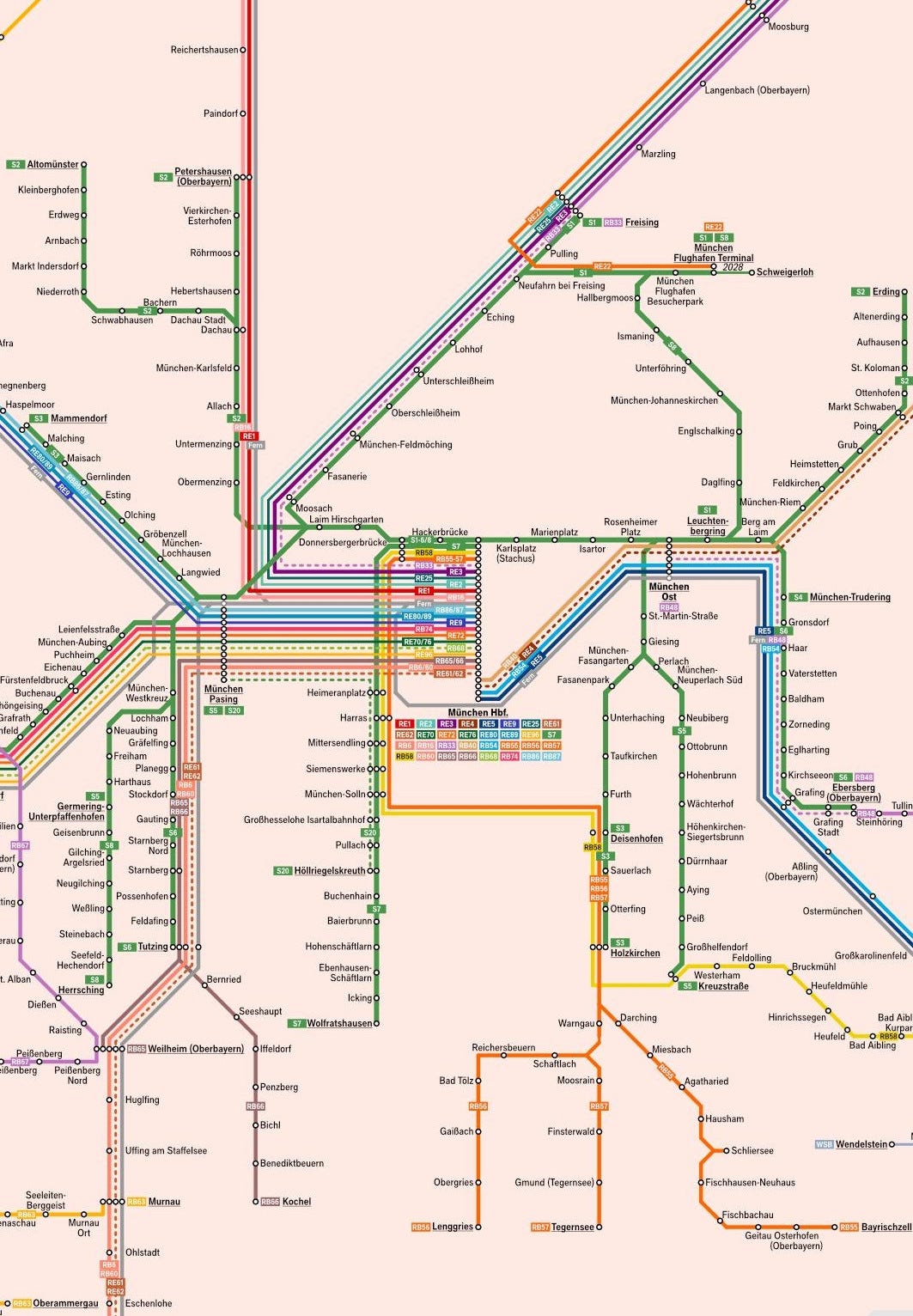

On the other side of the planet is the Munich S-Bahn, one of the oldest “modern” post-war regional rail operations. Facing a tight six-year deadline after being awarded the 1972 Olympics in 1966, Munich converted their existing regionalbahn regional train network into an S-Bahn, or “city rapid railway”. The Munich S-Bahn was created by building a tunnel through central Munich connecting the city’s existing Central Station and East Station. This tunnel serves as a trunk in which the various lines converge to provide a high-frequency east-west transit link through the urban core.

Unlike in Philadelphia, beyond central Munich the S-Bahn network serves as an overlay of the existing regionalbahn (RB) lines, which largely continue to operate directly into Central Station and terminate there, similar to how Metra trains today terminate at Union Station, or Ogilvie Transportation Center, or LaSalle Street Station, or Millennium Station. Munich’s S-Bahn branches are also consistently matched: the same line in the west will always connect to the same line in the east, all day long.

The above map helps to demonstrate how this network is fundamentally structured. Each individual line runs at regular intervals bi-directionally throughout the day; as lines converge closer to central Munich, the schedules are coordinated so trains are relatively balanced along the trunk, providing fast and frequent east-west trips through the heart of the city. In central Munich, the strength of the network is the trunk tunnel line between East Station (München Ost[bahnhof]) and Central Station (München H[aupt]b[ahn]h[of]), with the trunk continuing above ground further west. For riders who are traveling between any two stations along this trunk, it doesn’t matter which train they board since they all make all the stops, which allows the trunk to function like a rapid transit line.

Further out, the consistency of each line’s operations better serves riders traveling beyond the urban core. As an example, a rider who boards the S8 line at the Munich Airport (Flughafen München, east end of the yellow line) headed towards Herrsching (west end of the yellow line) will always have a direct connection. Compare this to Philadelphia, where taking the Airport Line in from PHL results in about a coinflip’s chance that the train will not go past Temple University, and also may not pair up with the otherwise-typical Warminster Line pairing during morning rush or in the late evening.

For these reasons, the CrossTowner vision takes more inspiration from the Munich S-Bahn model.2

CrossTowners for Chicagoland

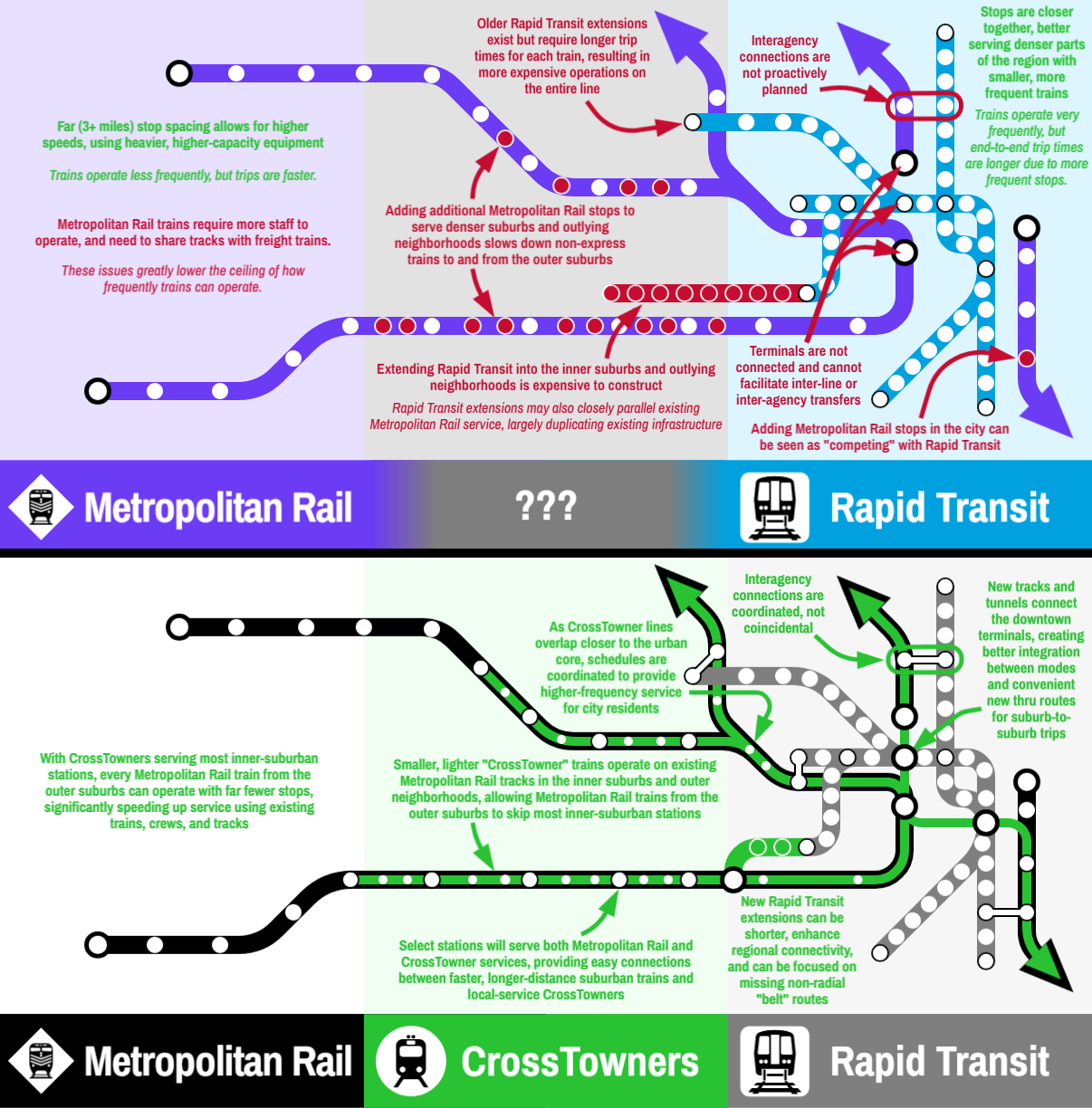

Here’s a graphic to help highlight some of the benefits of this kind of regional rail network in more of a Chicagoland context, and to illustrate the functionality of such a system as something of a hybrid between the CTA’s rapid transit network and Metra’s commuter3 rail network.

As we enter the NITA era, it is imperative that we begin planning and operating our transit network with a focus on regionality, and thru-running regional rail on its own provides benefits throughout the entire region:

· For Chicagoans, thru-running regional rail service (assuming a single tunneled connection between the UP-N/NW lines and the Metra Electric) would effectively create a ninth ‘L’ line between Metra’s Clybourn station and Hyde Park with direct connections to at least five existing ‘L’ lines and at least ten existing Metra lines. This trunk also allows for more direct transfers to a wider variety of services (e.g., Far South Siders could take trips to O’Hare simply by changing trains at Union Station rather than walking three blocks between Millennium Station and the Dearborn Subway), so even if a transfer is still required to complete a trip, the “transfer penalty” is far lower.

· In the outer neighborhoods and inner suburbs, regional rail allows for more convenient rail service on existing Metra lines in areas of the city far from even the most optimistic expansions to the ‘L’ network, and specifically improves connections to work centers beyond the Loop (O’Hare, Des Plaines, Evanston, etc.). With regional rail taking a larger role in “radial” rail service, future ‘L’ system expansions can focus on building a stronger urban network and shifting away from a strict hub-and-spoke model (e.g., building the Circle Line or the Mid-City Transitway).

· In the collar counties, regional rail operations allow Metra to operate more all-day express service on their busiest lines since regional rail trains will serve most of the local stops. In other words, even though CrossTowners themselves may not reach far into the collar counties, they allow for existing service to run at higher speeds with fewer stops, still providing a direct benefit.

NITA will undoubtedly have its hands full for the first few years in setting the foundation for the 21st-Century transit network Chicagoland deserves, whether that’s reimagining the bus network or establishing service standards or determining the best key performance indicators to track the progress of each agency and the network as a whole. Regional rail is a terrific example of what could be possible for our region as NITA gets established.

As we embrace a more regional perspective to how we plan, operate, and fund our transit network, having an ambitious-yet-attainable “moonshot” project to tie Chicagoland together will be an important contribution to demonstrating the additional value NITA can provide to the entire region.

While Metra has publicly committed to transitioning to a “regional rail” model, and while the NITA legislation will also hold them to that promise, Metra’s definition generally boils down to “run more trains”. While this blog will be the first to praise a proactive decision to operate more service, “regional rail” in most international contexts also include some level of operational thru-running and interlining.

London’s Elizabeth Line operates as something of a hybrid of the Philadelphia and Munich models, although with frequencies far higher than SEPTA Regional Rail the shortcomings of that model are less impactful.

Once again, using “commuter rail” to refer to Metra only to distinguish its operations from the international context of thru-running regional rail. This blog is well aware that Metra now calls itself a regional railroad, and encourages Metra to continue making advancements towards full regional rail.

2 thoughts on “Diverging Approach: The Missing Middle of Rail Transit”

Comments are closed.